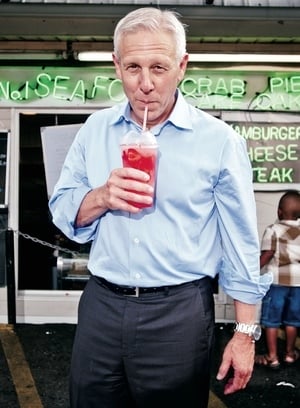

Monty Hoffman steps out of a trailer at the corner of Seventh and Water streets in Southwest DC and into the bright sunlight. It’s one of those perfect Washington days when outdoor patios are filled with people having a good time and parks are packed with bicyclists and runners. But while Hoffman is just a block from the water, the streets where he walks are nearly deserted.

Looking slightly out of place in a crisp white dress shirt, black slacks, and loafers, Hoffman barely seems to notice the desolation. Where others see a rundown motel and a parking lot full of tour buses, he sees potential. He envisions a cobblestone promenade along the water, a beer garden, and a bustling farmers market. He sees parks, hotels, historic tall ships, and a development of townhouses built on a pier. Most of all, he sees streets filled with people—couples eating dinner, friends on their way to a concert, families having a picnic in the park.

In September 2006, Hoffman’s development company, PN Hoffman, was picked from a field of 17 competitors to redevelop this stretch along the Washington Channel into the kind of world-class waterfront neighborhood DC has never had. For the last five years, the project has been mired in political and bureaucratic battles and slowed by the recession. But it’s finally moving forward—Hoffman and his team have begun to secure financing, and if the zoning commission approves their plans, they intend to break ground at the end of next year.

The Wharf—as the development is called—will cost more than $2 billion and borrow ideas from areas such as Seattle’s Pike Place, New York City’s Battery Park, and Italy’s Amalfi Coast. The hope is that it will extend downtown DC to the water’s edge and spark development of the city’s other waterfront areas.

But while many are excited about the plans, some fear losing the quiet way of life they’re accustomed to in Southwest DC. Others, such as those who live aboard houseboats docked at the waterfront, worry about being displaced.

Underpinning these local concerns is a bigger question. Fifty years ago, the federal government razed hundreds of buildings in Southwest DC and brought in forward-thinking architects and developers to create a neighborhood that reflected the most modern thinking of the time—much like the team at work today.

But as the ’60s-era developer found, creating a neighborhood from scratch is very hard to do. Given Southwest’s history, some may be wondering whether Hoffman’s team can pull it off.

***

More than a decade ago, DC mayor Anthony Williams stood on the deck of a destroyer docked at the Washington Navy Yard. Overlooking a bleak Anacostia shoreline, Williams promised that Washington’s waterfronts would one day rival those of Boston and San Francisco.

To understand why Washington has made such poor use of its waterfronts, you have to look first to the federal government, which owns most of the land touching the Potomac and Anacostia rivers. Along the rivers, the government built Fort McNair, the Navy Yard, and Bolling Air Force Base. Where the government didn’t erect military bases, it created parks—as you follow the Anacostia River toward the District/Maryland line, you pass Anacostia Park, the National Arboretum, and Kenilworth Park and Aquatic Gardens. Along the Potomac are the Lincoln and Jefferson memorials and the golf course at Hains Point. These monuments and parks draw lots of tourists, but because there’s almost nowhere to eat or shop, the riverfronts die after the sun sets.

Things began to change in November 2000, when President Clinton signed a bill allowing private development in the Southeast Federal Center, a 55-acre plot of federally controlled land along the Anacostia in Southeast DC.

“It was a unique land deal at the time,” says Harriet Tregoning, director of the DC Office of Planning. “It allowed us to begin thinking about creating some great waterfront neighborhoods, and it brought a lot of land that was previously not on our tax rolls into the city’s budget.”

The deal paved the way for creating the Yards—the burgeoning neighborhood that today surrounds Nationals Park—and acted as a catalyst for planning other waterfront developments. In December 2003, Mayor Williams unveiled the Anacostia Waterfront Framework Plan, a 20-year blueprint for turning blighted areas along the Anacostia into lively communities.

The Southwest waterfront was a cornerstone of Williams’s plan. Despite its prime location on the Washington Channel and proximity to the Mall, it had never come close to fulfilling its potential. Unlike Georgetown’s Washington Harbour, which filled with boaters and restaurant-goers on nice nights, the Southwest waterfront had become a grimy eyesore, isolated from the rest of the city by the Southeast-Southwest Freeway.

Next: Failure at the Waterfront

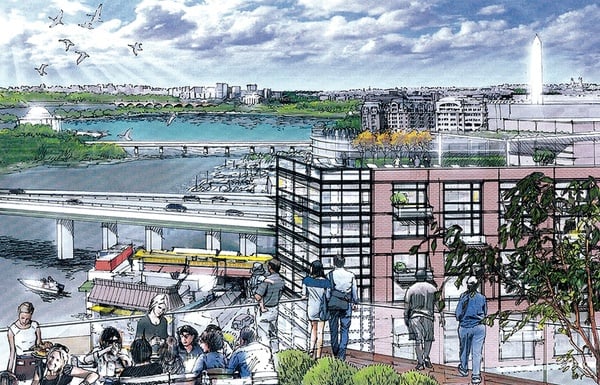

The Wharf will have many places to sit outside, some with views of the monuments along the Mall. Illustration courtesy of PN Hoffman

It may not look it, but Southwest is one of DC’s oldest neighborhoods. Plantation homes once lined the banks of the Potomac on what is today Bolling Air Force Base. Brick rowhouses began to go up nearby in the late 1700s and early 1800s.

Local historian Paul Williams says Southwest was a working-class community in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. “It was densely populated, thriving, and predominantly African-American,” Williams says.

The waterfront was bustling and crowded. Ice, lumber, coal, seafood, and produce arrived by boat. Lining the river banks were taverns, restaurants, and hotels as well as small shipbuilding operations and the city morgue.

But by the middle of the 20th century, Southwest DC had become rundown and overcrowded. Many homes didn’t have indoor toilets. “Its proximity to the Capitol was seen as an embarrassment,” says Williams. “The Soviets used images of Southwest with the Capitol in the background as an example of how democracy is a failed institution.”

In the 1950s, the neighborhood was targeted to become the first major urban-renewal project in America. Cities across the country were trying to figure out what to do with their deteriorating neighborhoods, and Southwest DC gave Congress a chance to test new theories of urban planning in its own back yard.

Using the right of eminent domain, the government razed hundreds of homes, businesses, and churches. In all, 560 acres were cleared and 23,500 residents displaced. Several of the foremost architects of the time, such as I.M. Pei and Harry Weese, were brought in to create a new community. They promised a modern neighborhood that would welcome families of all classes, including the low-income former residents who had lost their homes.

The project, in hindsight, was a failure. Despite its location in the heart of the District, the neighborhood was planned to look and feel like a suburb. The new Southwest came on the heels of New York’s Levittown, a planned suburb on Long Island emulated across the country. People didn’t want public transportation and pedestrian-friendly streets, the thinking went; they wanted highways, malls, and parking lots. The architects and planners replaced the city grid with dead-end streets and large superblocks; built the Southeast-Southwest Freeway, cutting the neighborhood off; and closed Fourth Street to make space for Waterside Mall, which never flourished and was torn down in 2007.

At the time, waterfronts weren’t thought of as places for leisure. Two highway-like main arteries—Maine Avenue and Water Street—make it hard for pedestrians to get to the water. Parking lots and mega-restaurants were built to draw busloads of tourists, not local residents. The marinas and docks were placed behind chainlink fences.

“Urban renewal reflected a time in America when the car was king,” says DC Council member Tommy Wells. “We lost the human scale.”

The redevelopment failed in another way: It laid the groundwork for future poverty and crime as many Southwest residents moved to public-housing projects east of the Anacostia River. Few of them could afford to return to the redeveloped Southwest.

Tregoning says that after the Southwest redevelopment, urban renewal became a taboo term. “Very few professionals in land development or community development would use the words ‘urban renewal’ because they have such a connotation of destruction, bad planning, and bad consequences.”

Hoffman hopes his team can undo some of the damage: “Urban renewal was a tragedy to the city. It decimated the neighborhood and didn’t give enough importance to churches, stores, schools, and all those things that make a community. We’re living that scar right now.”

***

The Maine Avenue Fish Market stands beneath a tangle of freeways in the shadow of the I-395 bridge. A collection of family-owned barges, the market is stocked with rows of fish, oysters, clams, and blue crabs. Servers dish out fried-fish sandwiches and mounds of collard greens and hushpuppies. Bob Marley and Otis Redding blare on a handheld radio, competing with the sound of cars speeding across the bridge above.

The fish market is boxed in by parking lots, and the only place to eat is a floating dock with bar-height tables where you stand and eat food out of Styrofoam containers. Still, it’s one of the only places along the 26-acre site that Hoffman and his team plan to save and incorporate into their new project.

“I like the chaos and honesty of it,” says Hoffman. “You’re not in a mall, that’s for sure.” He’ll clean the area up—remove the parking lots and exposed electrical lines—and build a new open-air market for the seafood vendors. He also foresees a farmers market and a beer garden nearby.

Aside from the area that surrounds the fish market, the developers are starting with a blank slate. Because most of the waterfront structures were demolished during urban renewal, there are no historic buildings the developers can restore and convert into condos or restaurants.

“Building from scratch is much harder,” says Stan Eckstut, principal at EE&K Architects, the master planner for the project. His firm has worked on several city waterfronts including Battery Park City in New York and Baltimore’s Inner Harbor East. “Preservation and restoration can be easier because they give you a place to start.”

Eckstut and his team don’t want the Wharf to look or feel like many of the area’s recent large-scale developments—National Harbor, Rockville Town Square, Shirlington Village. Rather than perfectly paved brick walkways, they want to incorporate unexpected alleys and an imperfect cobblestone promenade inspired by the uneven streets of Positano, a centuries-old village on Italy’s Amalfi Coast.

“I live in Greenwich Village in New York City,” Eckstut says. “It’s full of surprises, and it’s messy and urban. That’s what we want.”

Although Eckstut’s firm will design the first few buildings, the development team will also hire other architects to give the streetscape texture and diversity. “There will be a lot of contrasts—large, small, noisy, quiet,” he says. “The buildings will be changing and colorful.”

One challenge will be to make the new design feel as if it’s been part of the city for years. “You have to be careful not to let the engineers run amuck and make everything look perfect,” Hoffman says. “There’s got to be a romance element to it that overrides the efficiency.”

Most of the parking will be below ground, saving space for shops, restaurants, and parks. As you walk along the development from the 14th Street Bridge to the Titanic Memorial, the attractions will become quieter. The west side, where the fish market is, will have much of the dining and nightlife—including a venue for concerts and indoor sports events—while the east side will be more residential. Public space will take up more than half the site. Maine Avenue will have a neighborhood feel—that’s where you’ll find services such as a drugstore, a bank, and a barbershop.

The chainlink fences that line the docks now will be torn down. Hoffman plans to attract street performers and vendors, much like Seattle’s Pike Place.

Six piers will jut into the channel. In addition to the yacht clubs and dinner cruises that already call the Southwest waterfront home, there will be a pier where boaters can dock and come on land; a water taxi to shuttle people to Georgetown, Old Town, Nationals Park, and National Harbor; a pier that can be used for parties and events; space for historic tall ships; and a development of townhouses—with good water views—built on top of one pier.

Every couple of hundred feet, a small alleyway lined with cafes and shops will carve through the buildings and provide sightlines to the water. “We want it to feel crowded and congested,” says Eckstut. “That’s usually a sign of a popular place.”

Although there will be a few hotels, Hoffman says the Wharf isn’t intended to be a tourist destination: “It will have grit. It will have swag. The look and feel of everything needs to be authentic.”

Next: The Southwest is Hoffman’s biggest challenge yet

The new Arena Stage, which opened last fall, abuts the Wharf. Hoffman plans to add restaurants and a fountain near the theater. Illustration courtesy of PN Hoffman

The son of a contractor, Hoffman, 50, grew up on a farm in western Pennsylvania and knew how to lay brick and drive a backhoe by age 14. At the University of Pittsburgh, he studied civil engineering. One summer, he worked in a coal mine, spreading lime dust on the walls to keep the methane levels down. “It made me get straight A’s in engineering because I knew I didn’t want to do that forever,” he says.

After graduating, Hoffman moved to Washington, where he and three friends shared a two-bedroom apartment. He slept on the couch. “I had $400 and a van,” he says.

He landed a job as a project engineer at Donohoe Construction, where he worked for ten years, becoming director of operations. In 1993, he decided to try real-estate development. His wife worked in real estate, and he had just gone to her company Christmas party. Everyone seemed happy. “I thought, I want some of that,” says Hoffman.

He and Pete Nazelrod, a colleague at Donohoe, bought a rowhouse at 1605 16th Street, Northwest, in a crime-ridden neighborhood three blocks from Logan Circle. At the time, many were leaving DC for the suburbs. “People thought we were crazy,” says Hoffman.

He and Nazelrod worked on the house at night and on weekends. They did most of the construction themselves, and Hoffman’s dad came down from Pennsylvania to help. They built a large addition on the back and converted the house into six condos.

About 150 people came through the open house on the first day, and the condos sold out immediately. Hoffman and Nazelrod quit their day jobs and founded PN Hoffman. They took the money they made from the first project and bought two more.

PN Hoffman rode the crest of the housing market into the early 2000s, building loft-style condos and apartments all over Washington. “It was a glorious time,” says Hoffman, “one of the most fun times of my life.” Their company grew to 90 employees—they had their own construction division, sales department, and development group.

But by early 2006, Hoffman started sensing that the market was overheated—and that other developers were betting that prices would keep going up. “We looked at the math and would see that someone else would take it for that price, and we’d say, ‘That didn’t make sense,’ ” says Hoffman. “And then a whole year goes by and we realize that we’ve passed on all of it. We looked closely at 20 deals, and none of them made sense to us anymore.”

Around that time, Nazelrod decided to move back to his hometown in Montana. As the economy began to spiral downward, Hoffman had to lay off more than half of his employees. He began focusing on neighborhood-transformation projects because he felt that partnering with the government provided a hedge against the out-of-control real-estate market.

In spring 2006, Hoffman joined with Baltimore-based Struever Bros. Eccles & Rouse to answer the Anacostia Waterfront Corporation’s request for interest in developing the Southwest waterfront. The field was a who’s who of local and national firms—the JBG Companies, EastBanc, Akridge, Carr Enterprises, Madison Marquette, and the John Buck Company.

AWC trimmed the field to five, then two, before choosing PN Hoffman and Struever Bros. in September 2006. Says former AWC head Adrian Washington: “They had a great plan, they had great companies behind them, they offered a good deal to the city, and they had a track record of getting things done.”

The win changed the trajectory of Hoffman’s company—and marked the beginning of a long and frustrating process to bring the plans to life.

***

Since winning the bid, Hoffman has worked with three DC mayors and administrations, watched the Anacostia Waterfront Corporation dissolve, and seen many of his investors withdraw because of the recession. He also had to find a new partner, Madison Marquette, when Struever Bros. ran into financial trouble and backed out.

A slew of government organizations have a say in the project, including the Army Corps of Engineers, the National Capital Planning Commission, and the Commission on Fine Arts. On Hoffman’s team today are law firms, architects, developers, and construction companies. There’s also a network of 42 consultants from around the world—environmental engineers, water engineers, lighting specialists, noise and traffic experts, hotel specialists.

Hoffman estimates his team has been to 300 community meetings since 2006. He’s had to buy out some leaseholders, such as the nightclub Zanzibar, and make promises to keep others, such as the Maine Avenue Fish Market and the Capital Yacht Club.

“There are so many competing interests,” says Hoffman. “If you solve one problem, you create another. The answer is not to capitulate halfway on everything, because then you end up with average, which is not a worthy destination.”

After years of waiting, the project seems to be gaining momentum. In March, Mayor Vincent Gray announced that the nonprofit Graduate School USA will lease 190,000 square feet of office space along the Wharf. This summer, the Washington Kastles tennis team moved its temporary stadium from DC’s former convention-center site to Southwest, breathing life into the area and drawing attention to the upcoming plans.

There still are unknowns. The economy could go into a double dip, making it hard to shore up financing and stalling development—much like what happened to the neighborhood near Nationals Park, which has taken longer than expected to develop. The zoning commission could also take issue with certain aspects of the project. Even under the best-case scenario, Hoffman expects construction to take seven years.

Luring the right mix of retail, restaurants, and hotels will be crucial. Madison Marquette’s specialty is place-making—the art of bringing in desirable businesses and making the development feel lively and unique. “The goal is to create Washington’s next great neighborhood,” says Madison Marquette’s David Brainerd. If the Wharf is going to convince residents to come back time and again, it can’t have the same mix of chain stores that you see in developments across the country.

Nothing is guaranteed. But it’s hard not to get excited when you look at the renderings and three-dimensional models of the Wharf. And it’s important for the rest of DC’s waterfront that Southwest succeed. The recession stalled much of the development planned for the banks of the Anacostia River—a successful Wharf could give those plans a jolt of energy.

One of the biggest challenges to the Wharf is money. Hoffman has to figure out a way to make a profit. The many public parks on the site won’t generate income, and it’s expensive to put all of the parking underground. He’s also had to cut a lot of deals with leaseholders, some of them on unfavorable terms, to keep the project moving. Says DC Council member Tommy Wells: “He doesn’t have much room for not getting this right.”

What’s more, Hoffman is in unfamiliar territory—the Wharf is by far the biggest project he’s taken on. And he can’t draw on many successful examples of new developments that have the authentic feel he hopes to create. Says Hoffman: “We want to build today’s version of a working wharf. There really isn’t much precedent.”

This article appears in the September 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.