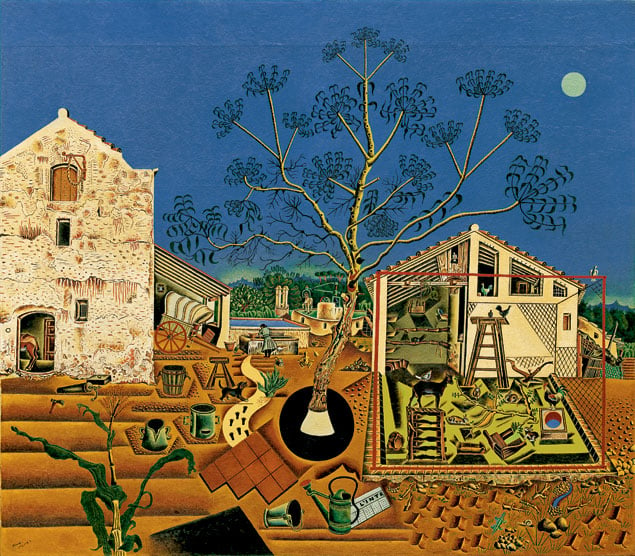

Few works of art have kept company with a more notable and

interesting cast of characters than has Joan Miró’s iconic painting “The

Farm.” The work (at left) is one of the centerpieces of the traveling Miró

retrospective whose only US stop, after stints at Barcelona’s Fundació

Joan Miró and London’s Tate Modern, is at the National Gallery of Art this

spring and summer. That’s in no small part because “The Farm” is part of

the National Gallery’s permanent collection.

The stunning painting exerted a strong gravitational tug on

other, widely dispersed works by Miró, but the story of how “The Farm” came

to reside in Washington–and its journey from 1920s Paris to Key West,

Cuba, and New York–is as interesting as the painting itself.

Miró, one of the most vital and long-lived painters of the 20th

century, is identified with his native Catalonia, that linguistically and

historically distinct bastion of good food, innovative architecture, and

passionate belief–whether in paganism, Catholicism, Judaism, Islam, or

anarchism–that has Barcelona as its capital. There the young Joan

(pronounced something like Sho-an) attended art school but didn’t

distinguish himself, whereas the slightly older Pablo Picasso had wowed

his teachers in Barcelona. Even Miró’s father wanted him to be a

businessman, not a painter.

Finally, to overcome illness and depression, Joan retreated to

the family farm near the village of Mont-roig and found some relief by

observing the daily lives of the farmers who worked the land. He took his

memories of Mont-roig to Paris in 1920, joining the diverse collection of

artists and writers there determined to transform a war-broken world

through art and literature.

One of them, Ernest Hemingway, was teaching himself to write

fiction by crafting short stories from his early exploits in Michigan–a

subject, as he later put it, that he knew enough to write well about. Not

far away, in a mean studio on Rue Blomet, the obscure Catalonian was

engaged in a similar pursuit, using oils and canvas instead of pencil and

notebook.

“The Farm” took a long time to finish and is seeded with images

that reappear throughout Miró’s later work, known for explosive color and

unfettered line, in which his imagination leaps off the canvases. But

there would be no other Miró painting quite like “The Farm,” a somewhat

surrealistic reflection of affection and longing that he considered one of

his best works.

Despite his own opinion, as Miró later told an interviewer for

La Publicitat, no art dealer “even wanted to look at” the

painting, much less exhibit it. One, the owner of the Galerie de l’Effort

Moderne, agreed to hang the painting in the basement on consignment. (Miró

later speculated that this was probably done as a favor to Miró’s friend

Picasso.) When it didn’t sell, the dealer suggested cutting it up into

eight pieces. Miró refused and took it back to the “utter misery” of his

studio.

Miró and Hemingway–both connected to Gertrude Stein, the

American writer and arts patron whose Paris salon included many painters

and writers–met in the early 1920s when the poet Ezra Pound saw Miró’s

work and introduced Hemingway to it. Hemingway fell in love with “The

Farm.” According to Miró, he “became so crazy about it that he wanted to

buy it . . . even though he didn’t have a cent in his pocket.”

Hemingway would embellish what happened next in an article in

Cahiers d’Art a decade later. Miró’s painting, Hemingway said,

“has in it all that you feel about Spain when you are there and all that

you feel when you are away and cannot go there.”

Hemingway wrote: “No one could look at it and not know it had

been painted by a great painter.”

Miró managed to get a show at the Galerie Pierre in 1925,

assisted by Evan Shipman, an exchange student and Hemingway’s chum.

Shipman had taken the gallery’s assistant to Miró’s studio to view his

work, and the assistant had offered Shipman the chance to buy any painting

of Miró’s at a good price before the show was hung. Shipman chose “The

Farm,” a move that couldn’t have gone down well with Papa Hemingway.

Shipman decided to offer the writer the chance to buy it

instead.

“Hem, you should have ‘The Farm,’ ” Hemingway said Shipman told

him. “I do not love anything as much as you care for that picture.” They

either flipped a coin (Shipman’s recollection) or rolled dice (Hem’s), and

Hemingway lost. But Shipman still let him buy it. Hem made the down

payment on what he remembered as 5,000 francs, Miró recalled as “2,000 or

3,000 francs,” and the gallery’s records say was 3,500 francs–about

$175.

Hemingway paid for it in part with money he earned delivering

produce, and when the final bill came due, he scrounged around for funds

in “various bars and restaurants” with the help of Shipman and the

novelist John Dos Passos.

“The dealer felt very bad because he had already been offered

four times what we were paying,” recalled Hemingway, who took the painting

home in a taxi, first telling the cabby to drive slowly so as not to

damage it.

Hemingway gave “The Farm” to his wife, the ever-supportive

Hadley, mother of his first son, for her 34th birthday. It hung on their

wall in Paris’s poor and noisy Rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, above a sawmill,

and would have witnessed the romantic poverty Hemingway evocatively

described in A Moveable Feast.

Hadley, replaced in Hemingway’s life by Pauline Pfeiffer,

remarried in 1933 and took “The Farm” back to America. In 1936,

Hemingway–by then living in Key West–asked if he could “borrow” the

painting, and Hadley, ever generous, consented. It was never

returned.

The writer’s eye was already on Cuba, and he moved there in

1939, acquiring a third wife–the peripatetic and talented war

correspondent Martha Gellhorn–and taking “The Farm”with him.

Hanging in Hemingway’s finca outside Havana, the painting was

as close as it would ever be to the sort of rural life it so vividly

depicted. Its neighbors on the walls were stuffed heads shot in Africa,

and they, too, witnessed a constant stream of visitors from Havana’s

demimonde, visiting celebrities, literary lights, friends, and

hangers-on.

Miró, meanwhile, had developed a different style of painting

and a passion. Profoundly affected by the Spanish Civil War of 1936-39, he

didn’t go to the front to fight, but he actively criticized the Spanish

dictator, Francisco Franco; produced propagandistic art for the

opposition; and spoke out often against the fascists.

Did “The Farm” provide inspiration for Hemingway while he wrote

For Whom the Bell Tolls, his romantic gloss on the Spanish Civil

War, a bestseller written mostly at the finca? Presumably it also

witnessed the writing of parts of The Old Man and the Sea,

Hemingway’s bullfighting oeuvre, as well as many letters, often abusive,

to editor Maxwell Perkins and others. By some accounts, the writer was

jealous of “The Farm” and kept it from view at least some of those

years.

Alcohol–and his own vituperation–was catching up to Hemingway

by 1959, when, then on his fourth and final wife, Mary, he agreed to loan

“The Farm” to the Museum of Modern Art. Hemingway was nervous about

exposing the painting to the hostilities stirred by Fidel Castro’s

revolution while trying to get it out of the country. He insisted that the

museum insure “The Farm” and send an emissary to squire it back to New

York, but no company would issue such a policy.

Hemingway finally agreed let the museum’s emissary, David

Vance, take the painting, but he ran into roadblocks: The original crate

sent by MoMA wouldn’t fit in the hold of the DC-7B that was to fly it out.

Vance left with the promise that the crate would follow the next day–but

it was delivered to the wrong airport. Meanwhile, Vance learned that he

needed a permit, but the newly installed officials at the Cuban National

Museum didn’t know how to get one.

Eventually, another plane reservation was made for Vance and

“The Farm,” for 3 in the afternoon of February 7, 1959.

When Vance got to the airport, more officials wanted a look at

what was inside the crate. They unloaded it, opened it, and inspected the

painting but were unable to reclose it properly because they had no tools.

A near-desperate Vance took “The Farm” into the cabin with him, in full

view of passengers, then missed his connecting flight. He finally landed

safely with his charge in New York early on a Sunday morning, and the

painting eventually went on display at MoMA.

Two and a half years later, Hemingway was dead of a

self-inflicted shotgun blast in his new home in Ketchum, Idaho. “The Farm”

was still at MoMA and, even there, continuing to tug at old, somewhat worn

heartstrings.

Hadley wanted the painting, which had been borrowed from her

nearly 30 years before, returned to her. But Mary Hemingway, heir to the

writer’s estate, refused. The two former wives ended up in court, with

Hadley finally agreeing to a titular settlement of $20,000 in

1964.

Mary Hemingway, living in New York, took possession of “The

Farm” from MoMA.

It wasn’t until a dozen years later that the painting finally

began its journey to Washington. In early 1976, the charming director of

the National Gallery of Art, J. Carter Brown, contacted Mary to tell her

about the much-anticipated construction of the East Building and ask her

to donate “The Farm” to the museum’s collection.

Mary replied that several museums had made the same request,

and though she hadn’t made a decision, she was “aware that I must do so

soon,” in part because she was concerned about the painting’s

condition.

Brown asked if he and Vic Covey, head of the National Gallery’s

conservation department, could pay her a visit. The request proved

fortuitous. Brown’s memo of June 14, 1976, states that Mrs. Hemingway was

“cordial and warm” and obviously impressed with the gallery’s annual

report.

Before Brown left, “Mrs. Hemingway indicated that that

afternoon she would be signing a new will in which the picture would be

left to the National Gallery.”

The painting was loaned to the museum by Mary Hemingway for the

1978 exhibit “Aspects of Twentieth Century Art,” in the East Building. It

was returned, then came back in 1981 and was again on view. “The Farm”

formally entered the National Gallery’s collection in 1987 but has

continued to travel to art institutions around the world.

Joan Miró continued working until his death in 1983 at his home

in Palma, Majorca, outliving his enemy Francisco Franco by several years.

By that time, Miró’s work had come to embody an aesthetic that was at once

earthy and poetic–and utterly Spanish.

The diversity of Miró’s creative output is staggering, and the

sheer number of works makes a traveling retrospective like this spring’s a

major challenge. Yet “The Farm” remains a touchstone, a youthful codicil

of Miró’s deepest associations, what National Gallery curator and head of

modern and contemporary art Harry Cooper calls “a résumé of his entire

life in the country.”

Miró said more than once that he was happy that Hemingway

bought his painting. No one wants to say what “The Farm” might be worth

today–Miró’s “Painting-Poem,” from 1925, sold earlier this year for $26

million–but the dollar value is largely irrelevant. Hem was right about

its primal power, and he concluded his 1934 article in Cahiers

d’Art with a tribute to Miró that even elevated image over words:

“[T]he thing to do is look at the picture, not write about

it.”

James Conaway writes often about travel and culture and is the author of “Vanishing America” and other books. His new novel is due early next year. He writes a blog at cjonwine.blogspot.com.

Related:

Art Preview: “Joan Miró: The Ladder of Escape” at the National Gallery