Among all the stresses and worries weighing on DC mayor Vincent Gray, the fact that the District’s top prosecutor, US Attorney Ronald Machen, is zeroing in on him must loom large.

DC’s government scandals are infamous: Marion Barry on camera with his crack pipe, bribery at the DC Taxicab Commission, a $48-million scam in the tax office. Yet the ongoing corruption probe into Gray’s 2010 campaign—coming on the heels of criminal investigations that took down two DC Council members—has rocked Washington like never before.

Machen, as the politically appointed head of the federal prosecutor’s office, doesn’t need to dig into the minutiae of cases. That can be left to lower-ranking prosecutors. But when asked if he’s personally involved in the Gray investigation, Machen smiles.

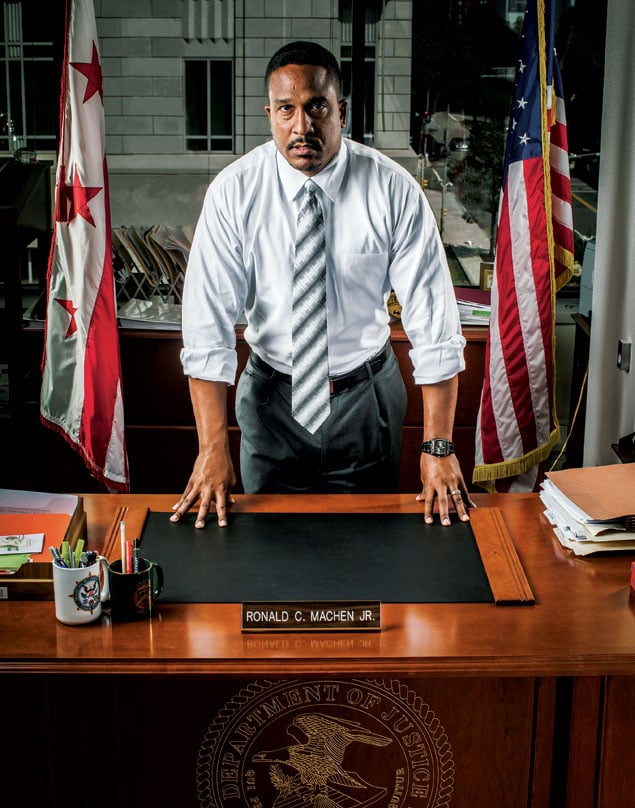

Seated in an oversize leather armchair at one end of his massive office overlooking Fourth Street, Northwest, he says that yes, he is very involved, then laughs at his own understatement.

Before Machen can continue, his spokesman, Bill Miller, interrupts to remind him that technically he’s not supposed to use Gray’s name because the mayor has yet to be charged with any crimes and hasn’t been identified in court documents. “We call it the Candidate A investigation,” Miller says.

But if the identity of Candidate A is supposed to be a secret, it’s the worst-kept one in Washington. So far, Machen and his team of prosecutors have gotten guilty pleas from three of Gray’s campaign aides, and it seems only a matter of time before more members of the mayor’s inner circle—perhaps even the mayor himself—will fall.

Machen and Gray are caught in a high-stakes game of chicken: Will Gray give in to calls for his resignation first? Or will Machen and his investigators beat him to the punch, dealing a blow so incriminating that Gray is, at best, forced out of office, at worst, into a courtroom?

There’s no other job in the country like Machen’s. He’s one of the nation’s 94 US Attorneys, but as US Attorney for the District of Columbia, he has a uniquely diverse portfolio. He handles the sophisticated cases typical of a federal prosecutor—national-security matters, complex securities frauds, public corruption—but his office serves a dual purpose. Because DC doesn’t have an elected district attorney to go after its street criminals, Machen also oversees the prosecution of drug offenses, murders, rapes, and other crimes.

Asked what his priorities were when he became US Attorney, Machen lists public corruption first. From the beginning of his tenure, he wanted to emphasize holding officials accountable. If citizens can’t trust their government, he says, it weakens the democratic system: “The people of this city deserve ethical, strong leadership. And when people violate the law who are in positions of trust, there are going to be consequences.”

It’s hard to doubt him. Even as his office deals with budget cuts and a hiring freeze, he has aggressively allocated resources to investigations of DC officials, expanding his fraud and public-corruption unit and creating a special team of a dozen prosecutors who collaborate on the DC corruption cases. Machen often sits in on the team’s meetings, and he has assigned his principal assistant US Attorney, the office’s second-in-command, to lead it.

Aside from the Gray investigation, Machen’s office—the country’s largest US Attorney’s Office, with more than 350 lawyers and a budget of nearly $73 million—has secured guilty pleas in the recent corruption investigations of DC Council members Kwame Brown and Harry Thomas Jr.

Machen is living up to the reputation he’s built over the course of his career—first as a young prosecutor in the US Attorney’s Office in the ’90s, then as a partner in the white-collar criminal-defense practice at the high-end firm Wilmer, Cutler & Pickering (which later became WilmerHale)—as a dogged investigator with an eye for even the smallest holes in a case.

By Machen’s own admission, he can be a micromanager. He talks through trial strategies with prosecutors. He asks about key witnesses, meets with defense attorneys, and in the DC corruption cases has been involved in plea deals. Machen could leave these details to his line prosecutors—the lawyers who investigate and try cases—as many of his predecessors have, but that’s not how he likes to do things.

In addition to talking tough, Machen looks tough. With his six-foot-one frame, broad chest, and thick neck, the 43-year-old former Stanford wide receiver could be mistaken for a retired pro athlete. He wears a sharp suit, wingtips, and a goatee. He has a pierced left ear, and the diamonds in his wedding band occasionally glint as he gestures to emphasize a point.

The bags under his eyes hint at the grueling hours and stress of his job, but he doesn’t sound fatigued: “I get up, and I’m charged to come in here every day.”

His work, after all, isn’t done.

Machen had been an associate at Wilmer, Cutler & Pickering immediately after graduating from Harvard Law in 1994. He then left for a year to clerk on the federal appeals court in his hometown of Detroit. He could have returned to Wilmer, but when the opportunity to become a prosecutor arose, he jumped at it.

“I wanted to learn how to try cases,” Machen says. “You just don’t get that opportunity as an associate at a firm.”

Jeb Boasberg, now a judge on the US District Court for the District of Columbia, started a few weeks ahead of Machen in December 1996 in the US Attorney’s Office, where they shared an office and became friends.

They were in the homicide unit together, four years into their tenure as prosecutors, when Machen decided to return to private practice at Wilmer, Cutler & Pickering in 2001. Before he left, Machen handed off one of his cases—a grisly matter in which an estranged husband shot his wife and her lover—to Boasberg.

Machen had prepared a summary of his investigation, known as a prosecution memo. Such memos are usually 10, maybe 15 pages long.

“He handed me a 50-page prosecution memo that detailed all the incredibly exhaustive steps he had taken in all facets of the case,” says Boasberg. “He essentially handed me an unlosable case. This was not a high-profile case, but he had treated it like one.”

Jamie Gorelick, former US deputy attorney general and now one of the most prominent partners at WilmerHale, recalls arriving at the firm in 2003 and immediately taking note of a lawyer she describes as “a young superstar out of the US Attorney’s Office named Ron Machen.”

Machen was helping run one of the firm’s biggest cases, a matter for Boeing that Gorelick also worked on. She was particularly impressed by his ability to develop strategy and to assess witnesses and facts.

Machen got an early taste of DC scandal while working on the firm’s pro bono investigation of Harriette Walters, the midlevel manager in the DC tax office who embezzled more than $48 million. Though the US Attorney’s Office conducted its own investigation of Walters, the DC Council separately retained WilmerHale to perform an independent probe.

Partner Bill McLucas headed the effort. Prosecutors were concerned that the WilmerHale investigation would interfere with their work, but McLucas says Machen, a respected alumnus of the US Attorney’s Office, put them at ease.

Machen primarily defended clients in white-collar criminal matters during his time at the firm, experience that colleagues say has helped him identify weak points in the cases he’s involved with as US Attorney.

“He’s always thinking about what he would do if he were defense counsel,” says criminal-division chief Mary McCord, one of the senior prosecutors involved in the DC-corruption investigations. “I like to think that even though I’ve done this 17 years, I can still put on a defense hat. But oftentimes he’ll say before I’ve thought of it, ‘If I was a defense attorney, I’d do this.’ I think that’s been helpful.”

In 2009, when President Obama nominated him to be the District’s top prosecutor, Machen was successful in private practice and surely comfortable—the average WilmerHale partner takes home more than $1 million a year; Machen’s hourly rate was $875.

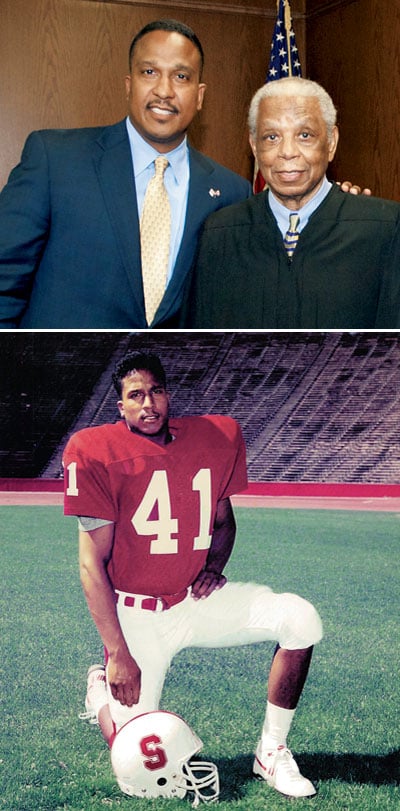

As US Attorney, Machen makes $155,500, but he says the position is “a dream job.” After his Senate confirmation, he was sworn in by the man he calls “the biggest mentor of my entire career,” Judge Damon Keith of the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, a civil-rights icon often mentioned in the same breath as Thurgood Marshall.

Keith, who was 87 at the time, flew in from Detroit for the occasion. Standing before a packed room at the federal courthouse on Constitution Avenue, he led Machen through the oath of office. Machen’s wife and sons were by his side, and his parents were in the audience.

Machen had clerked for Keith shortly after law school. Keith, now 90, says Machen is like a second son.

Keith remembers him as being a little overconfident when he first showed up for work. After playing football at Stanford and graduating from Harvard Law, Keith says, Machen thought he knew it all: “We had to take a little of that swagger out and still keep him courageous and strong.”

Machen grew up in the middle-class Detroit suburb of Southfield. His father was a chemist at Ford, and his mother worked for a purchasing company that was a Ford subsidiary.

Machen’s parents saved to send him to one of Michigan’s most elite prep schools, Cranbrook—the same one attended by Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney.

Though he says it broke his mother’s heart that he wanted to move so far away when he chose to go to Stanford, his parents encouraged him. Machen had begun playing football when he was 12 and walked on at Stanford as a wide receiver. He says he likes that the game takes both physical and mental toughness.

The talent for the sport seems to run in his family. Machen’s young sons, ages 8 and 11, already play football, and until recently his oldest son, from a previous relationship, was a middle linebacker at Georgia Tech.

Machen loves hanging out with his kids—he calls them “my guys”—and tries to make time to jog or bike in Rock Creek Park on weekends. Most days, he wakes by 6:30 to get the boys ready for school or summer camp, and he arrives at his office by 9 or 9:30. His wife, who is in marketing, takes care of the kids in the evenings while Machen works at the office until 9 or 10 at night.

At the urging of DC congressional delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton, who recommended him to Obama, Machen moved his family from Silver Spring to DC so he could be part of the city he’s charged with protecting.

Machen tapped an old friend and colleague from his first go-round in the US Attorney’s Office to be his second-in-command.

Vincent Cohen Jr. is the son of Washington legal legend Vincent Cohen, the first black partner at the law firm then called Hogan & Hartson, now Hogan Lovells.

The junior Cohen started as an assistant prosecutor about nine months after Machen. Though Machen was only slightly more senior, he took Cohen under his wing, showing him the ropes and offering advice on how to manage the various cases assigned to first-year prosecutors.

“He left no stone unturned,” Cohen says. “He’d put a number of witnesses—more than probably anyone else in the office—into the grand jury for his cases just to make sure that any defenses, any outs, any avenues that somebody might try to take, were blocked by testimony.”

Together at the helm of the office, the two have made an aggressive team, most notably leading the wide-ranging probes into public corruption among DC officials.

Though unrelated, the investigations into ex-council members Harry Thomas Jr. and Kwame Brown and the Gray campaign hit almost at the same time.

First came the accusations in March 2011 from former mayoral candidate Sulaimon Brown that the Gray campaign had paid him to stay in the 2010 race and promised him a city job if he continued to attack Gray’s chief opponent, incumbent Adrian Fenty.

By June 2011, the feds had begun investigating Ward 5 council member Thomas for spending more than $350,000 of the city’s money on vacations, a motorcycle, and a luxury SUV, among other items.

Then, in July of that year, Machen’s office revealed that prosecutors had been investigating Kwame Brown for misusing campaign funds during his 2008 reelection bid for his at-large seat on the council.

And those are just the matters out in the open—the US Attorney’s Office handles many more confidential investigations than public ones.

Last fall—a few months before the FBI raided Harry Thomas Jr.’s home—Machen decided a special team of prosecutors was necessary to handle the onslaught of public-corruption cases. He asked Cohen to lead the effort and act as his eyes and ears.

Though Cohen’s administrative responsibilities, including personnel and budget matters, could be a full-time job, he says the public-corruption casework takes up as much as 75 percent of his time.

And the guilty pleas are stacking up: Harry Thomas Jr. pleaded guilty in January to theft and tax charges and was sentenced in May to 38 months in prison, the first sitting DC Council member to be charged with and convicted of a felony; two other people have also pleaded guilty in connection with Thomas’s scheme. And Kwame Brown pleaded guilty in June to bank fraud and violating DC campaign law.

Now the focus seems to be narrowing on Candidate A himself. Thomas Gore and Howard Brooks, both members of Gray’s campaign treasury team, admitted to secretly paying off Sulaimon Brown. Gore also pleaded to obstructing justice, and Brooks pleaded to making false statements—both federal offenses.

An even bigger bombshell dropped in July, when public-relations campaign consultant Jeanne Clarke Harris admitted to evading campaign contribution limits by funneling political donations from businesses owned by Gray financier Jeffrey Thompson through coworkers and relatives. The scheme resulted in a $653,000 shadow campaign to elect Gray. (Thompson hasn’t been charged as of this writing, though feds have seized boxes of his documents and records, and he has hired powerful criminal-defense lawyer Brendan Sullivan.)

“One of the things I’m most proud about with these public-corruption cases is they haven’t gone to trial,” Machen says. “We’ve put together such strong cases in the investigative part, in the grand-jury process, that there’s just no reason. These aren’t folks that are just going to wilt and cry because the US Attorney comes calling. They only plead when there’s no option.”

Gray, whose office didn’t respond to requests for comment for this story and who has stayed mostly quiet about the investigation, has previously told reporters: “This is not the campaign that we intended to run.”

Gray’s lawyer, white-collar criminal-defense giant Bob Bennett, a partner at Hogan Lovells, is not among Machen’s critics. In an e-mail, Bennett writes that in investigating his client, the US Attorney “has been totally responsible and professional” and, though “an aggressive advocate for the government,” Machen has been “very fair.”

On a Friday afternoon this summer, Machen stands before an audience of young people at HD Woodson High School in Northeast DC. He’s there for the second annual youth summit organized by his office, with the theme of “breaking the silence on youth violence.”

As an Ivy League-educated black man in one of the city’s most powerful jobs, Machen has seized the chance to be a role model to the predominantly African-American public-school students he frequently speaks to.

“Why are we here?” he begins. “The answer is simple: Too many young people are dying in DC.”

He’s there to convince the kids to stay out of trouble, but he doesn’t come off as preachy. Maybe it’s all those years he spent on the football field—he sounds more like a coach giving a locker-room pep talk than a law-enforcement official there to boss them around.

Machen tells the students they have to stay vigilant to guard their futures—easier said than done, particularly for those without support systems at home.

He says a major factor in his decision to return to the US Attorney’s Office was the opportunity to build trust between DC’s toughest neighborhoods and law enforcement. He hopes that in addition to the public-corruption work, this will be an important component of his legacy. As part of his outreach, he’s appeared at basketball games and other events to build ties in neighborhoods such as Anacostia that rarely have a warm relationship with prosecutors.

Machen’s focus on the community draws frequent comparisons to Attorney General Eric Holder, who was DC’s US Attorney in the ’90s when Machen was a line prosecutor in the office. Like Machen, Holder devoted time and resources to neighborhood outreach.

“I remember [Holder] saying in my interview with him that the most important function of the job is to protect folks in their own communities,” says Neil MacBride, who was an assistant prosecutor with Machen and is now US Attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia in Alexandria.

Machen’s community initiatives aim to end the “anti-snitching” culture that hinders investigations in DC’s most crime-ridden areas. One of the first efforts Machen launched is a partnership with churches to host town-hall meetings encouraging residents to cooperate with law enforcement and educating them about what his office does and how it can help them. The idea is that if citizens know and trust prosecutors, they’ll be more likely to help combat crime.

Church leaders say Machen’s efforts have made a difference in how their congregants view his office.

“Initially, turnout wasn’t great,” says Reverend Kendrick Curry of the Pennsylvania Avenue Baptist Church in Southeast DC, who has held events with Machen. “But over time, it’s grown immensely. Once people see you on a regular basis and there’s some rapport, they begin to come out.”

Curry has been pastor at his church for nearly a decade, but he says this is the first time he’s ever met the city’s US Attorney or anyone else from the prosecutor’s office.

Machen also attends church east of the Anacostia River, at both Pennsylvania Avenue Baptist and Matthews Memorial Baptist Church.

But the US Attorney is up against long-held and often well-founded fears. In parts of the city such as Wards 7 and 8, the belief that helping law enforcement is akin to a death wish runs deep. Last November, prosecutors won convictions of three men in what had been a 2½-year campaign of violence and intimidation against witnesses to a 2007 murder in Southeast DC.

The culture isn’t the only obstacle in Machen’s way: His office, like the rest of the federal government, has been hit by budget cuts and a hiring freeze. While homicides are at a half-century low in the District, the unit responsible for prosecuting murder cases this year lost half a dozen seasoned prosecutors and had to move others from elsewhere in the office to fill the vacancies. Other violent crimes are increasing: Arrests for aggravated assault in DC are up by 13 percent compared with the same period in 2011.

And while the public-corruption cases appear to be going well for Machen, he had a high-profile stumble earlier this year in the prosecution of retired baseball star Roger Clemens for allegedly lying to Congress about taking performance-enhancing drugs.

The first Clemens trial ended abruptly and embarrassingly for Machen’s office when prosecutors mistakenly showed jurors evidence that had been barred from court, forcing the judge to declare a mistrial. Prosecutors could have dropped the case, but they retried it earlier this year. Clemens was acquitted in the retrial after a quick jury deliberation—a huge setback for the government. Clemens’s lawyer, Rusty Hardin, said at the time that jurors weren’t even close to convinced by the prosecution: “They believed the whole thing was an abuse of the process.”

Machen, though, doesn’t have the luxury of dwelling on past shortcomings. If history is any lesson, his time as the District’s top prosecutor is almost over. Most of his predecessors haven’t stayed longer than four years, and he’s coming up on three. There are already rumblings in Washington’s legal community that Machen will land back in private practice.

That’s where several of his predecessors have ended up, including Jeffrey Taylor, who jumped from the US Attorney’s Office to Ernst & Young, where he led the fraud-investigations practice. He’s now general counsel of Raytheon Integrated Defense Systems.

The position has catapulted others into higher-level government jobs, such as Kenneth Wainstein, who went on to become George W. Bush’s Homeland Security adviser, and of course Holder, the current attorney general.

Machen insists he isn’t thinking about anything other than his current job. He’s busy focusing on the investigation that will more than likely define his tenure as US Attorney—an investigation that remains very much open.

For now, Mayor Gray still sits in his office in the Wilson Building, about a mile west of where Machen is perched above Fourth Street talking about how his prosecutors are “attacking” the public-corruption cases.

Machen can’t say when he expects the Candidate A matter to end—or whether Candidate A ultimately will be charged—but he offers this assurance about the investigation: “We’re moving as fast as we possibly can.”

This article appears in the October 2012 issue of The Washingtonian.