Secrets, says

Frank Warren, are “the currency of intimacy.” He knows, because he has more than half a million

stashed in his basement. The Germantown resident is the founder of the website PostSecret,

which was launched in 2005 as an art project and has since evolved into an online

community with more than half a billion pageviews.

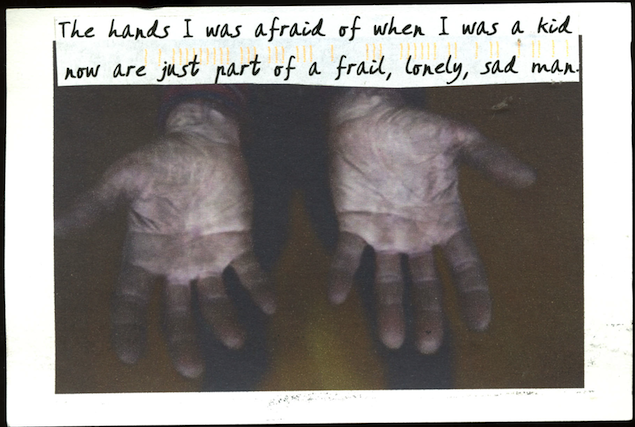

Each Sunday, Warren curates a selection of 24 handmade postcards from the several

thousand that arrive in his mailbox weekly, and posts them on the site. The secrets

range from heartfelt (“I’ve had four new cell phones since my father died three years

ago, and I still add his number to my contact list”) to humorous (“When no one is

looking, I walk up the stairs on all fours. I’m 30 years old”). PostSecret has spawned

five books, speaking tours all over the world, and an iPhone app, but the website

is currently undergoing its biggest transformation yet—from a blog to a piece of live

theater.

The genesis of the PostSecret play started in 2010, when three Canada-based artists

and producers—actor and consultant

Kahlil Ashanti, talent manager

Justin Sudds, and playwright and performer

TJ Dawes—were looking for a new theater project. For the past six years, Ashanti had been

performing his own one-man show,

Basic Training, which had run to sold-out houses three times at the Edinburgh Fringe and been touted

as a

New York Times critics’ pick during its off-Broadway run. In the autobiographical piece, Ashanti

describes how he felt as a teenager about to join the Air Force when his mother finally

revealed that the abusive man he’d grown up with was not his father.

“It’s an intensely personal and exhausting story to tell, but it’s been interesting

to see how it inspired people,” says Ashanti. “I wanted my next project to be something

similar, and something that had a footprint, both socially and commercially.” Sudds’s

wife, Erin, mentioned PostSecret, of which she’s a fan. (PostSecret’s community is

largely, although not exclusively, female.) “Justin and I looked at the website and

were instantly moved by it, and we called TJ and came up with a proposal for how we

could make it best fit the stage. Then we cold-called Frank’s literary agent and pitched

him the idea.”

Warren is used to people approaching him with ideas regarding the site, and he’s intensely

protective of both the secrets he’s gathered and the community he fosters. In the

past he’s turned down several proposals for collaboration, including one from TV’s

own self-help guru, Dr. Phil. “I was apprehensive at first, just like I always am,”

he says. “I want to make sure that whatever I do, I don’t violate people’s trust and

I protect what’s special about the project. But the more I spoke to Justin and the

whole team, the more I felt all our values were in line.”

Warren sent out a tweet from the PostSecret account mentioning that the site was looking

for a theater to do workshops in, and one of the many responses came from

Blake Robison, the former Round House Theatre artistic director, whose wife was also a fan of the

site (she became one of the show’s original performers during its first ever workshop

at Round House Silver Spring). Robison offered the theater as a space, and Warren,

who used to work in Bethesda at the National Institutes of Health, accepted.

The challenges in bringing the site to life as a piece of theater were numerous, but

Warren had a model in mind: Eve Ensler’s

The Vagina Monologues. “She gives voice to unheard points of view, and breaks this taboo, allowing people

to have conversations about something that’s very important,” says Warren. “And the

way that she’s created her play works: It tours not just the country but the world

in a way that really attracts and embraces a lot of people. And ultimately, she raises

so much money for important causes through her art. It’s a wonderful model that I

hope to emulate.”

The play’s structure is still undergoing changes, but the version that played to a

sold-out house at Round House Bethesda last Friday incorporates theater, multimedia,

live music, and audience interaction. Three actors—Ashanti and local performers

Susan Lynskey and

Emma Jaster—performed stories from PostSecret’s archive, acting out a sizable number of different

postcards as well as longer stories Warren has been told via e-mail and at PostSecret

campus events. During one, Warren’s own voice recalls his time as a volunteer at suicide

prevention charity Hopeline, when he called the police to intervene when a woman was

about to jump off her balcony. In another, a discussion about PostSecret leads to

a mother being told by her daughter that her father has been abusing her.

PostSecret typically has several recurring themes, ranging from sexuality to grief

to faith to body image, but there are also moments of levity, which the show re-creates.

“The important thing for us to focus on was the human condition,” says Ashanti. “All

these secrets—what do they have in common and how do they connect us? The biggest

challenge was making sure it wasn’t too depressing, because, as Frank says, the good

things people tell—it’s the not-so-good things they keep as secrets.” One of the show’s

funniest moments reveals the most common secret people send in: an admission to peeing

in the shower.

As the actors perform, secrets are projected above their heads, incorporating the

visual aspects of the site. During intermission, audience members are encouraged to

submit their own secrets, and the actors select a few to read in the second act. The

actors were also encouraged to spontaneously read their own secrets, although in keeping

with the projects’s emphasis on anonymity, it’s never revealed which ones are theirs.

“Hopefully the play is just part one,” says Warren. “Part two is when you get in the

car and drive home, and have a conversation with your spouse or your parents or your

friend that you’ve never had before. Maybe through the play, people can connect in

different ways with others and their deepest selves.”

The PostSecret play will now travel to Saginaw, Michigan, for another workshop, and

then to Cincinnati, Ohio, for a production at the Playhouse in the Park, where Robison

recently moved to become artistic director. At last week’s Bethesda performance, Sudds

was contacted by a producer who expressed interest in staging it in New York. Wherever

the play ends up being performed, both Ashanti and Warren think that theater, with

its unique, irreproducible structure, is the ideal format for PostSecret’s next evolution.

“I think that as time is passing, technology is changing our relationship to art and

entertainment,” Warren says. “Recorded music is becoming less valuable, books are

becoming less valuable, film is becoming less valuable—this is all unfortunate, but

you can see the economic reality of it. But live events are becoming more precious,

and really becoming the performances that can touch us as other forums are losing

their impact. In theater, something’s there for a moment and then it’s gone. I feel

so privileged to be able to share these stories in a way that holds people’s attention

that other forms coming across the screen maybe don’t have the ability to anymore.”

For more information about The PostSecret Play, visit the PostSecret website or follow the play on Twitter.