Six white votive candles are left burning at the base of the

wall after everyone has gone. There are only the candles and the flickers

of light that dance above them. Lit from below, the names carved into the

face of the wall don’t stand out as words. Instead you see fingerprints

where a name has been touched, marked by the oils from living

skin.

It’s almost 2 in the morning on Memorial Day 2012. Usually the

Vietnam Veterans Memorial would have a carpet of mementos and letters in

front of it on this, the eve of Rolling Thunder, when thousands of

veterans, motorcycle riders, and onlookers congregate in Washington.

Indeed, they thronged to the wall earlier and left hundreds of cards,

grandchildren’s drawings, and teddy bears plus one rolled-up canvas that

might have been a tent or a tarpaulin. But tonight the rangers have

cleared everything away by order of the Secret Service. The President will

speak here tomorrow.

All of these items are, officially, suspect.

Bernie Pontones got here late, after the sweep-up. Bernie’s a

sixtyish guy with a long white ponytail, a veterans’ advocate in Grove

City, Ohio. He placed a candle in front of the wall for each of six men

who remain in his thoughts.

A teddy bear decorated with uniform name tapes was left by a member of a California chapter of Vietnam Veterans of America.

Photograph from the book Offerings at the Wall courtesy of Turner Publishing.

Ask Bernie about them and he’ll tell you what he remembers or

has pieced together: Greg, the kid he knew from church, was killed when a

runway was mortared and his plane flipped and burned. Sammy, who’d been in

Bernie’s platoon, turned to his buddy and yelled, “Get down!” instead of

getting down himself. Gerald, who trained with Bernie at Fort Benning, was

in country less than a month when he bought it. Bernie doesn’t know how.

The sergeant, who heard a noise and threw his grenade. It bounced off a

tree right back at him. His body shielded the blast for the rest of the

men, including Bernie. Robert, from high school—Bernie doesn’t know how or

why or when, but he died late in the war, when the end was in sight and

death seemed particularly cruel. Ron, who had volunteered for active

combat. They say he slipped in the rain, fell, and somehow detonated his

grenade. Damnedest thing.

Despite the solemn setting, Bernie’s almost giddy tonight,

leaving burning sage all around the wall, less because he believes in the

herb’s healing powers than because it strikes him as a silly, New Agey

thing to do. And he believes in the healing powers of silliness. He

laughs, remembering the monkeys that threw rocks at them over there.

“Lifer fragged himself” is how he tells the story of the sergeant, the

grenade, and the tree.

This candle-lighting ceremony is cathartic for him, he says, a

long overdue release: During the war, there was no time to process all the

sudden death. As they said at the time, “F— it. It don’t mean nothing.”

You had to postpone your mourning.

“If you were distracted by grief,” Bernie says, “you couldn’t

keep yourself safe.” You’re fighting a war. You’ll have the rest of your

life to grieve.

Bill Schools is here with Bernie. He’s more interested in

conversation than in the wall tonight. Bill’s a Rolling Thunderer who’s

here in the wee hours because that’s the only time Bernie will come.

Bernie is still bothered, all these years later, by crowds and camera

flashes.

So now the members of this small contingent from Vietnam

Veterans of Ohio, who drove eight hours to get here, have the wall to

themselves.

Chris Smith came with them. He doesn’t look for any names. He

kept his distance over there—that’s how he protected his psyche. Chris

doesn’t look at the wall for more than a few seconds, even when standing

right in front of it. His eyes don’t rest. He doesn’t always come along,

but Bernie and Bill persuaded him this year.

The men leave, and as soon as their voices fade, all that

remains is their flickering gifts.

Without Bernie to explain them, the candles have no story.

They’re six pieces of a puzzle that could depict anything at

all.

The wall is about stories. The little ones are told in the

letters and objects left behind—eccentric items that speak of matters so

intimate they may be indecipherable except to two people—one living, one

dead. Bullet casings soldered into a circle. Five cans of fruit salad. A

teddy bear, loved threadbare. A harmonica. An ace of spades. A handful of

gravel. A model carousel. A toothbrush. Graduation tassels. They’re all

pieces of a larger story still under revision, about the meaning of an

unpopular war conducted in a small country among three superpowers with

competing geopolitical ideologies—a proxy war with inchoate objectives

that killed a lot of people and sent others home in varying states of

disrepair.

That story is complicated.

Along with this offering was a note: “Left for our beloved only son, Dead at age eighteen.”

Photograph from the book Offerings at the Wall courtesy of Turner Publishing.

But it’s one the National Park Service relentlessly pursues.

Bernie’s candles are gathered up by park rangers and put into big blue

boxes. The boxes are hand-trucked and golf-carted to a temporary storage

room near the Washington Monument, where they await transport to the

Museum Resource Center, or MRCE, pronounced “mercy,” a gleaming modern

facility in Maryland that houses 40 historic collections from National

Park Service sites around the region. The candles get 30 days or more of

isolation and are checked for organic matter—flowers, potpourri,

marijuana, unsealed food, tobacco, anything that might carry mold. That

stuff is “deaccessioned”—thrown out to protect the rest of the

collection.

Then the artifacts go into the cotton-gloved hands of Duery

Felton Jr., curator of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Collection, a

decorated Vietnam veteran who has devoted himself to this work for 25

years.

Felton is a young-looking 65. He’s compact, with a shaved head

and a cane he sometimes carries but rarely uses. He works in blue cotton

garments that resemble scrubs, and he moves with grace. Give him a mask

and he might be a surgeon.

Duery Felton doesn’t want to be written about. Ask him about

his thoughts and feelings—how his life would be different if there were no

Vietnam Veterans Memorial or what the hardest part of his job is—and he

answers the question he wishes you asked instead.

He pauses, touches his fingertips to his closed eyelids, and

begins: “I can tell you this one because he has died.” He answers your

question about him by talking about others. Even then he won’t give a name

or even an approximate year. Part of his sacred duty is keeping the

secrets of the 58,282 people named on the wall and their loved

ones.

Get him off the record and his face softens, his eyes widen,

and he smiles easily. But he’s wary of expressing opinions and thoughts of

his own or imposing his meanings on the objects he curates. Being

interviewed is part of his job, but he speaks as a representative of the

National Park Service, not as Duery Felton.

Profoundly injured during the war, Felton will sometimes tell

some of his story and sometimes not. He’ll sometimes confirm or deny what

others have written about him, and he’ll sometimes smile and change the

subject. Before media and researchers are allowed into the facility where

the collection is housed, they must sign a document affirming that

collection staffers have the right to refuse to answer questions or give

personal opinions.

Which of course they do with or without such a document. But

Felton prefers it this way.

There’s no mystery about Felton’s importance to this project.

Even a generation later, veterans and veterans’ groups remain mistrustful

of the government but not of Felton, who’s their go-between. Objects show

up at the wall addressed to him.

“Duery—you will understand,” reads an envelope containing a war

diary. When rumors went around that the collection was stored in a leaky

room with rats, Felton invited veterans’ groups to see the acid-free boxes

and the temperature-controlled rooms where the objects are kept, alongside

Clara Barton’s furniture and Frederick Douglass’s piano.

Even now, Felton proudly shows off a tableful of insect

traps—used—each with a number denoting where in the facility it was

placed. The contents of the traps are entered into a database to track

incipient infestations. Felton is guarding treasures.

His insistence on his own privacy, however, has attracted all

the more curiosity. In, of all places, Wiki Answers, where anyone can

answer any question at all (Q: How many types of rhinos are there? A:

Five), one of the questions is “What happened to Duery Felton Jr. in

Vietnam?”

It remains unanswered.

Bernie’s candles will be examined, cataloged, wrapped in a

plastic bag, and put in a blue box. And there they’ll sit, with the

hundreds of thousands of other pieces of grief in the collection, until

we’re all dead.

According to legend, the first object left at the wall was

someone’s dead brother’s Purple Heart, thrown into the cement as the

foundations were poured for the black granite panels. By the end of the

opening ceremony 30 years ago this month, lots of people had laid down

mementos. No one anticipated that. No one had any idea people’s immediate

reaction would be to do what so many returning vets say they did in

Vietnam: leave something of themselves behind.

This impulse was an entirely new phenomenon, unknown at other

memorials. It seemed to be instinctive, long before anyone knew, or even

suspected, that the things they left would be kept.

Eleanor Wimbish, a homemaker from Cecil County, Maryland, near

the northern end of the Chesapeake Bay, wrote to her son Billy as soon as

she ran out of thank-you notes for the flowers and food people had sent to

his funeral. She just kept writing, letters she wouldn’t finish, or would

finish, then rip up.

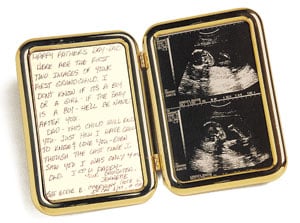

Lots of letters are addressed to “Dad.” This one came with sonogram images of a soldier’s grandchild. A cast of the child’s hands was later left at the wall.

Photograph from the book Offerings at the Wall courtesy of Turner Publishing.

“It was all a secret until the wall,” she says. She lived near

enough to become friendly with the guys who stood vigil at the

construction site—vets who heard rumors of threats to bomb the memorial.

She brought them sandwiches.

The first year after the dedication, she wrote seven letters to

Billy and left them at the wall. The second year, six. Before anyone

realized the value in keeping what people left at the wall and before

there was a systematic collection system, Wimbish was leaving letters.

Before she knew anyone would see them or save them. Before she knew she

wasn’t the only one who felt compelled to leave something. She couldn’t

tell you why. Can’t tell you for sure even today.

She doesn’t write to Billy anymore. She’s 85 now, and her

husband, another son, and two grandsons have passed, too. Too many letters

to write. But Felton pulled all her letters for her, as he will for others

who ask, so she could come see them again this year, in case it’s her last

chance.

The memorial’s design is such a great story you’ve probably

heard all about it. The vet, Jan Scruggs, who watched The Deer

Hunter in 1979 and then concluded that the names had to be

remembered. His struggle with Congress to get a plot of land on the

Mall.

The design contest was open to everyone. Entries had to

incorporate all the names of the dead and missing members of the US

military and had to make no political statement about the war. As the

planners put it: “The hope is that the creation of the Memorial will begin

a healing process.”

Essentially, the contest asked: Please design a piece of art

that makes no statement whatsoever while somehow attending to the psychic

wounds of hundreds of thousands of people. And—oh, yeah—leave room for

almost 60,000 names.

A committee of eminent artists would judge entries by number,

not by name, a little decision that proved huge: There would be no stigma

attached to an idea by an absolute nobody.

Up in New Haven, Yale undergraduate Maya Lin and her classmates

were taking a course in funerary architecture, and the contest became

their final project. Lin came down to look at the piece of land where the

memorial would sit, and she came up with the design we have today. The

committee unanimously chose it. Somehow, over the objections of some

veterans and Congress members and the Secretary of the Interior, her

vision got built.

The footage from the press conferences is still amazing. In the

first one, Lin giggles and tosses her hair. In another, she joins a

roomful of suited veterans and officials at least ten years older than she

is. She wears a giant, ridiculous gray hat, begging to be called eccentric

and arty. She doesn’t giggle in that one. In a 1994 documentary, Maya

Lin: A Strong Clear Vision, she hardly ever smiles. You learn a lot

from your first press conference.

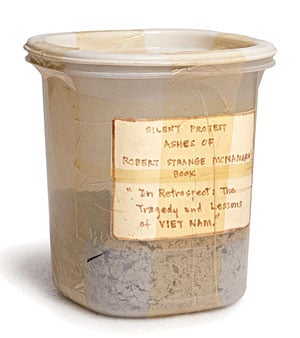

The ashes of a copy of the 1995 memoir “In Retrospect” by Robert S. McNamara, who was Defense Secretary from 1961 to 1968.

Photograph from the book Offerings at the Wall courtesy of Turner Publishing.

Her design was the first of what Kirk Savage, a University of

Pittsburgh professor of the history of art and architecture, has dubbed

“therapeutic memorials,” created as psychologists began to notice

something they called posttraumatic stress disorder in the vets who came

home to a populace that wished they would shut up about the

war.

Lin’s design is really about the visitor’s experience at the

memorial, a giant V carved into the earth like a knife wound. The viewer

journeys below ground level with the names of the dead, emerging into the

light again when leaving the names behind. The lettering is only about

half the standard one-inch size for inscriptions. You have to get close to

read it. The shiny black granite reflects you as you look at it. The

carved surface invites you to touch it; when you do, a ghostly hand meets

yours. Some early visitors were startled when they got their pictures

developed to see themselves in the wall, taking the picture.

The memorial doesn’t leave you alone. It pulls you in. It

encourages you to dredge up long-buried feelings and to experience them

right there, in semi-public, alongside other mourners.

Veteran Paul Baffico, at a recent luncheon for wall volunteers,

said: “You can physically touch a memory. You can put your hand on a name.

And it’s 6:30 am, July 23, 1970. I can smell it, hear it, feel it—my gun,

the cordite, the madness of a firefight, Hueys coming in. How the hell did

I survive this?”

Everyone who cries at the memorial has something in common.

It’s a mending wall. It invites a particular contemplation by those who

survived and now face the confounding privilege of becoming

old.

And finally, in a way, the wall is a monumental, daring

deception.

By removing all context from the wall, Lin only seemed to be

declining to make a statement. But the absence of context, of course,

wasn’t without meaning—because the memorial says nothing about glory or

sorrow or heroism or democracy or freedom, nothing about making the world

a better place or making a sacrifice for a worthy cause. All that’s left

is loss of life, the only thing everyone could agree on, a single

existential truth. These people are gone, and that’s all there is to say

about the war.

In 1984, when the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund officially

gave the memorial to the country, the National Park Service began

semiofficially collecting all the artifacts left at the wall. By then,

Duery Felton was on the board of the DC chapter of Vietnam Veterans of

America, and he visited the facility regularly.

None of the staff at MRCE had Felton’s experience. Someone left

a package of M&M’s at the wall, and Felton knew it might be because in

the war M&M’s were the placebo of choice when morphine pills ran out.

Anything he didn’t already know he could find out from his network of

veterans.

By 1989, the Park Service had hired him part-time as a museum

technician. Even now, in his more senior role as curator, he’s part-time

so that he has time for veteran activism and volunteering.

Felton is careful not to impose his own meaning on the objects.

He doesn’t correct spelling or punctuation when transcribing letters. If a

package or letter comes to the wall sealed, it stays that way. He insists

that Metro cards, car keys, fast-food spoons, and parking tickets be

collected because nobody can say they aren’t meaningful. It might, he

says, be the car the guy always wanted to buy. Nobody knows the

collection, the outpouring of grief, as he does. The collection is part of

him and he of it. There are artifacts he takes out just to look at every

once in a while, but he won’t say which.

The mysteries are always there: the black lace panties, the

Bazooka Joe bubblegum comic strips, the fishing bobber, the Mickey Mouse

ears, the single high-heeled shoe, the GI Joe action figure, the golf

trophy, the taxidermized deer hoof and ankle, the television, the set of

coins hundreds of years old.

Felton compares the mysteries to Odysseus and the Sirens: “Plug

your ears with wax or you’ll crash on the rocks. It’s seductive, but you

have to learn to read and not to read.” That’s one of the hardest jobs he

has—to read the letters. The content has to be archived, but the reader

can’t, day after day, week after week, let everything fully touch

him.

The letters Felton reads but doesn’t read show poignantly what

changed—and what didn’t—with the passing years. A young woman tells her

father he would have been the best daddy in the world. A soldier can’t

forgive himself for not realizing how badly his buddy was hurt. A

37-year-old woman writes to her lover, who’s still 21.

Mustache, khakis, round pale face. Mike Brady is at the wall at

midday on Memorial Day, standing by a bench, smoking a cigar. He’s already

finished his beer.

“Every year I come back and have a beer and a cigar with my

brother.”

Mike is alone.

Here’s Mike’s story: He and his brother were in Nam together at

the same time, in staggered service. Mike still had months to go, but his

brother, Brad—three days from going home—promised to smoke a cigar for

Mike when he got back. Brad never made it.

The note says these are the casing and bullet that killed one Henry Lee Bradshaw on August 12, 1968.

Photograph from the book Offerings at the Wall courtesy of Turner Publishing.

Mike seems at peace, about 40 feet from the wall, where there’s

some shade, gesturing with his cigar. Nobody else seems to be here by

himself.

“They used to let me smoke over by the wall,” he says. “Some

people would bother me, but the ranger knew I was a vet and said, ‘Just

don’t leave the butt.’ ”

Mike says he’s a surgeon who has retired to Bluemont, Virginia.

He makes the trip for the cigar and the beer every year. He used to feel

sad, but not anymore. He remembers the last day he felt sad about the war.

It was the first year of the wall, camping out with other veterans the

night before the monument was to be dedicated. They all went to see it for

the first time, jumping the barriers. By flashlight it was immense,

incomprehensible—he couldn’t find his brother’s name. He didn’t care. The

wall was for both of them. When the sun rose and he found his brother’s

name, he didn’t feel sad anymore. He’s had a good life, and war is

war.

That’s Mike’s story.

“The wall does it. All the names are on there. It’s like the

person’s spirit is on there.”

This is Edward Tick, author of War and the Soul, a

therapist from Albany who’s been treating posttraumatic stress disorder

for decades.

Tick says the wall works on two levels: It’s a symbol, and it’s

a repository. These aren’t the same thing; they answer different

needs.

After the war, veterans and family members of the dead had no

time or place to grieve and felt socially rejected for remembering a war

everyone wanted to put behind them. The wall is a place of honor in the

nation’s capital, acknowledging the sacrifices they all made and that the

whole country mourns.

But people can also unburden themselves, Tick says—put down

some of the things they’ve been carrying, literally and figuratively, and

grieve at last. The names make the wall like a grave, as if the person is

present.

“Here in the sacred place, you can talk to the person and

complete a relationship that was cut short,” Tick says. “He is

here.”

As the hymn says, you can lay your burden down.

These were left with no explanation, but some military nurses have said they wore frilly undergarments to feel feminine under their fatigues.

Photograph from the book Offerings at the Wall courtesy of Turner Publishing.

It’s a random evening at the wall, and you have to stretch a

bit to remember this is a sacred place. A pack of teenagers doesn’t even

change the topic of conversation as they walk by the names. They’re

debating Batman versus the Avengers.

Two brothers under age ten circle around behind the wall, where

the top is at ground level. They take a picture of their sister taking a

picture of the wall.

Families march by, the kids with glazed expressions from seeing

all of DC’s majesty in an afternoon, the parents trying and failing to

think of someone the kids might have heard of who’s on the wall. A young

woman on a cell phone asks, “Yeah, but what was his middle name?” A couple

out for a romantic monuments tour doesn’t seem to know what to do. Perhaps

they came here by accident but feel they owe the wall a little time, a

little discomfort. After a minute, they look at each other and nod,

walking off again.

It has taken a lot of time, but these kids are now able to walk

past the wall untouched, blessed with the confounding privilege of

ignorance.

Jan Scruggs, having won the battle to memorialize the war so

many were eager to forget and seeing his dream become one of the most

visited landmarks in DC, faces a different battle now. Plans are under way

for an education center nearby to explain the war to those who were born

after it was over—now about half of the US population. The education

center, perpetually about two years from completion, will display a small

fraction of the estimated 400,000 objects that have been left. And,

Scruggs hopes, that will be it—the Park Service will stop collecting the

offerings at the wall.

While important artifacts are still being left—Scruggs calls up

on his iPhone a recent photo of a bloodied Viet Cong canteen with a bullet

hole through it, leaning against the wall—MRCE just doesn’t have the

resources to collect, catalog, and store every object in perpetuity, as is

the mandate of this collection.

MRCE has an enormous backlog—estimated at about 200,000

objects, roughly half the collection—and not enough staff to catch up.

There are seven employees at the facility, but they don’t work on just

this one collection. And the stream of offerings isn’t letting up, even

now.

They’ve learned a lot over the years by trial and error—that

cans of tomato products burst, that printer ink smudges and runs onto

other objects, that clothing deteriorates without cold storage. A canteen

with 40-year-old bloodstains teaches them more.

Nobody’s sure when or if the Park Service will stop collecting

it all. Felton loves this aspect of the collection, that it’s uncensored

and unjuried, that no judgment is made on what’s valuable and what’s not.

Everything is valuable because someone wanted it included.

The contents of the collection are not on public display. But

in a book or museum exhibit or article, someone can see the diaper pins or

Alcoholics Anonymous chips, and the story gets told.

Felton has trouble explaining to younger workers how it used to

be, why Vietnam vets are sometimes amazed that strangers now thank them

for their service. It’s just hard to explain.

Without question, Felton’s sensitivity has made it easier for

some to give up their precious memories, the treasured and fraught bits of

war, the shrapnel that slowly works its way out of wounds and gets carried

to the wall, to be laid down. Left in good hands.

But the fact that everything is gathered and stored means the

collection is unwieldy and absurdly time- and

resource-intensive.

For example, Sarah Ettinger, a paid intern, is cataloging the

objects in a box from 2010. She selects an item; consults a book, The

Revised Nomenclature for Museums, to see how to describe it; and

notes the description on a paper form. Entering the form into a searchable

database is another step.

The item is a piece of yellow posterboard, 11 by 14 inches,

with GOD BLESS AMERICA in silver glitter and a crude, construction-paper

American flag. It’s signed by a Pittsburgh elementary-schooler who

presumably made it for a class project.

Ettinger flips around in the nomenclature guide. This is a

“communication artifact, advertising medium.” It’s not really, but that’s

as close as the nomenclature gets. She has a small space on the form to

identify this poster in a way that distinguishes it from any others. It’s

yellow, which is an unusual color, and fairly thick.

There’s a stack of posters like this one, probably one from

each kid in that class. Cataloging them all and figuring out how to note

their differences will take her the rest of the day.

The easy answer—the one her colleagues will have to reach

eventually, though Felton resists it—is that this artifact isn’t worth an

employee’s time, that no one will see it once it’s in its box, that it’s

generic and hardly likely to be significant to anyone’s healing process.

Right now, though, this is a museum artifact because a little boy put it

down in a sacred place and left it there.

Memories can’t survive on their own. They live in brains,

bouncing off things and slowly taking new shapes. One of Ed Tick’s vets

doesn’t remember being blown up with his best friend but prays that the

horrible things he dreams now, over and over, are symptomatic of the

confusion of trauma and not what really happened—that it’s a story he’s

telling himself, trying to make sense of the absurdity that is

war.

There’s the fog of war, and there’s sometimes a different fog

that follows.

Mike Brady, the retired surgeon with the cigar who said he was

healed by seeing his brother’s name, doesn’t show up at all on Google. At

least not in Bluemont, Virginia, or any town nearby. No retired surgeon

with that name on Google, either.

The phone number he gave is a disconnected land line in

Herndon. It could have been a transcription mistake. But that guy—the vet

who’s not sad, who comes to the wall at peace and leaves cigars not

because he’s anguished but because he’s healed, the one with the great,

uplifting story—the name he gave for his brother isn’t on the

wall.

Legend has it that the first object left at the wall was a Purple Heart. Many more have been left there since.

Photograph from the book Offerings at the Wall courtesy of Turner Publishing.

That doesn’t make the story untrue. Maybe something

happened—maybe, fighting demons, he panicked when asked his name and gave

a false one. Can it be that he has no story at all, that he’s just a rogue

playing an odd trick on a credulous writer? But he was there, at the wall

on Memorial Day. He had an earnest, plausible story. It can’t all be fake.

There must be an explanation.

Fifty miles away, down Snickersville Turnpike in Bluemont,

Rosemary draws a blank. She lives by the old train station, knows

everybody in town, and her father was in Nam, but she doesn’t know Mike

Brady or any retired surgeon. Neither does Scott at the post office or

Lynnette or Amy at the wounded-warrior retreat for Walter Reed patients

that will open next year. Lynnette shakes her head in woman-to-woman

sympathy.

“He gave you a fake name and a fake

number?”

Bubba and Pete at Tammy’s Diner know everybody in town—but no

Mike Brady or any vet who visits his brother every year at the wall and

smokes cigars.

If it’s all made up, why did he pick Bluemont, a town of 3,000

where it just happens that a retreat for wounded vets is being built? Did

he have this story ready in case he got the chance to punk

someone?

There’s got to be more to the story of Mike Brady. There is

more, even if we’ll never know it. Mike Brady, whatever he’s about, is

another artifact of the Vietnam wall.

So many of the collection’s mysteries can never be unraveled.

You can research and conjecture, but you never have the story unless the

donor gives it up. Felton warns that you should never impose your own

meaning on the things left at the wall, but of course you do. It’s the

seductive power of the collection, that an object will mean something to

you without your knowing what it meant to the person who left

it.

Vietnam veterans returned home to an America deeply divided and

sick of talking about the war. Felton was advised not to wear his uniform

in the civilian world. He was called a baby killer.

So Felton developed another kind of Vietnam wall. There are

certain things that to this day he’ll discuss only with other vets. To

outsiders, he might tell a story shrouded in hypotheticals, expressed in

the second person and without resolution:

“Imagine it’s happened to you. You’re captured with your best

friend, and he’s injured, he’s got gangrene in his leg, and if you don’t

give up information, they won’t give him the penicillin. And after a while

the gangrene rot starts to smell.”

You can research, ask questions, and conjecture. You can find

that Duery Felton grew up in Northeast DC and attended Smothers

Elementary. That at the time of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which made

Vietnam a big war, Felton’s parents—as DC residents—had never been able to

vote for President.

You can find in previously published works that Duery Felton

Jr. volunteered for the Navy, like his father and brother, but a heart

murmur disqualified him. You can find that he then enlisted in the Army.

You can ask him about it, and he’ll tell you he was drafted, actually, and

without hesitation tell you the address on G Street, Northwest, where the

Selective Service office was.

You can find that he was awarded a Bronze Star with a V for

valor for going back into a kill zone three times to rescue the wounded

near the Cambodian border in 1967.

“A Viet Cong with a machine gun yelled right at me, ‘GI, you

die!’ and opened up,” he told the Washington Post in 1990. “The

ground around me exploded like the inside of a popcorn maker.”

Now he doesn’t want to discuss it.

Dollar bills are often left as a symbolic fulfillment of a promise. Some are torn in two—one half is left at the wall, the other kept as a remembrance.

Photograph from the book Offerings at the Wall courtesy of Turner Publishing.

You can find some references to this incident as the time and

place he got his life-threatening injury, the one that would keep him at

Walter Reed for years. You can find other references that it wasn’t that

incident. You can guess that the latter is right.

You can read in Gail Buckley’s book American Patriots: The

Story of Blacks in the Military From the Revolution to Desert Storm

that he faced racism in the Army, a fact that, as Duery himself might

tell you, the North Vietnamese would exploit in propaganda pamphlets that

asked African-American soldiers: Why fight here when your civil-rights

fight is at home?

You can find that half his face was ripped off by a tank in an

accident in 1968, that he remembers the combat surgeon telling him they

were trying to save his life. You can read that he spent years at Walter

Reed in an atmosphere so racially tense that a skipping record of “My

Girl” by the Temptations incited a discussion of the merits of music made

by black people, which led to a “mini race riot,” with whites and blacks

“in wheelchairs, on crutches, carrying IV bags,” all fighting. Afterward,

he and his chapter of Vietnam Veterans of America pressured the government

over the US military’s use of Agent Orange and helped welcome troops home

from Desert Storm.

You can figure out on your own that somehow, after more than 30

surgeries and with constant pain, Duery Felton transformed himself from a

broken, angry man mistrustful of authority into a government employee who

bridges that divide for thousands of others. That he’s absolutely

necessary to one of the most interesting jobs in Washington, a curator’s

position that usually requires a graduate degree. He is a man now

emotionally healthy enough to revisit Vietnam every day, every

hour.

One time, he opened a Ziploc bag containing a bandana and was

overwhelmed by the smell of the jungle. He’s a man who never knows if he’s

going to see an object from his own unit. Who reads but doesn’t read. Who

gets calls at all hours, at his home, about veterans and the collection.

But you can never know how he does it or know if this job is what gave him

back his peace of mind, or even kept madness at bay, if that’s a story he

chooses not to tell.

It must be a hell of a story.

Rachel Manteuffel (rachel.manteuffel@gmail.com) is an actor and writer who lives in Southwest DC. Find her on Twitter @rachelman2.

This article appears in the November 2012 issue of The Washingtonian.