There have always been spies, but espionage is far from static. Like so many things, what drives a person to spy on the US on behalf of foreign interests changed drastically after the collapse of the Soviet Union. And these motivations appear to be changing again in the post-9/11 era.

Today, spies are more racially diverse and adept at using technology, but most of all, they’re more idealistic than during the Cold War. That’s among the findings of a 2008 study by the Defense Personnel Security Research Center (PERSEREC), which published a series of reports analyzing what compels American citizens to spy on their own country.

In the 1980s, 74 percent of spies did it solely for money, the study found. But since then, the majority of Americans caught spying on America were not recruited by a shadowy foreign agency or in it for financial benefit. Of the 37 Americans caught spying inside the United States since 1990, only one was solely motivated by monetary gain, the study found.

This shift in motivation is likely the result of a marked demographic change in the spy population. The traditional Cold War spy was a younger, white male. Now, while still mostly male, the modern domestic spy is older, more educated, more likely to be married, more likely to be non-white, and more likely to be motivated by what the study calls “divided loyalty.”

The study cites “divided loyalties,” which it defines as “allegiance to a foreign country or cause in addition to or in preference of allegiance to the United States,” as the most drastic and significant change in espionage motivation. Prior to 1990 it had been the sole motivation in only 20 percent of cases, but leaped to 57 percent after.

The study attributes this increase to globalization and changing immigration patterns. From 1947 to 1989, 80 percent of American spies caught working for foreign entities were native born. From 1990 to 2007, the number dropped to 65 percent with the remainder being naturalized citizens. More importantly, spies with cultural ties to other countries shot up from 10 percent before 1990 to 50 percent after.

One example is the case of John Joungwoong Yai, a businessman and naturalized American citizen of Korean descent, who for three years in the early 2000s sent unclassified information to North Korea and was plotting to obtain classified information before his arrest in 2003 for acting as an agent of a foreign power.

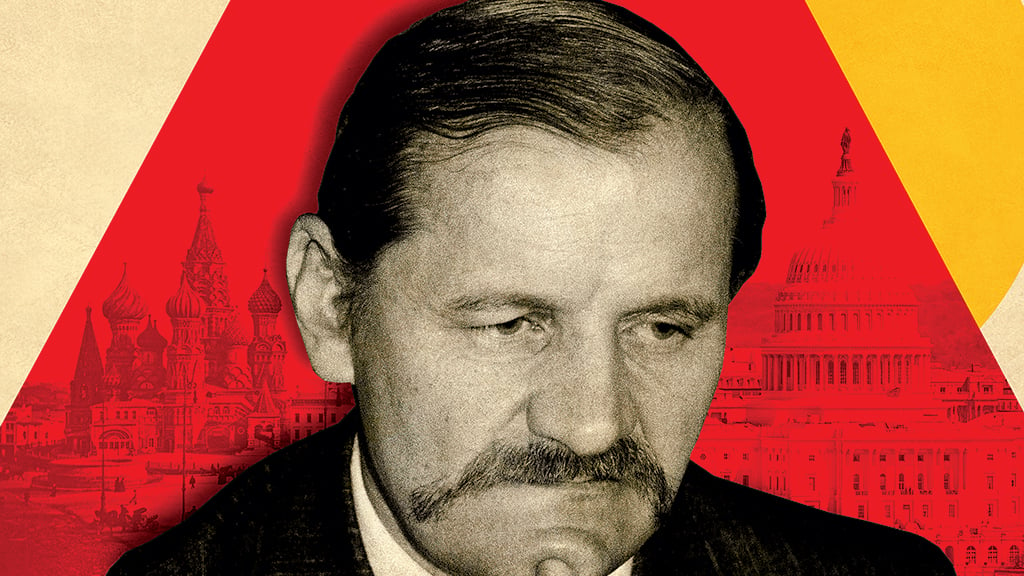

This demographic shift seems to be, in part, a response to the vacuum left by the Soviet Union and the repositioning of priorities for the War on Terror. As of 2007, Russia was the destination for only 15 percent of the information collected by the known domestic spies that PERSEREC studied. Asian counties, including China, and Latin American countries, especially Cuba, are collecting more now.

The number of known spies in the US peaked in 1985, but the 1980s were also the the peak of success for domestic counter-espionage. Only 60 percent of attempts by American spies to pass information, usually to the Soviet Union, were successful. The 1990s and early 2000s saw the success rate bounce back to 84 percent, almost matching the early Cold War. This increase may be due the shift toward better educated spies and the proliferation of costumers for American intelligence since the 1990s.