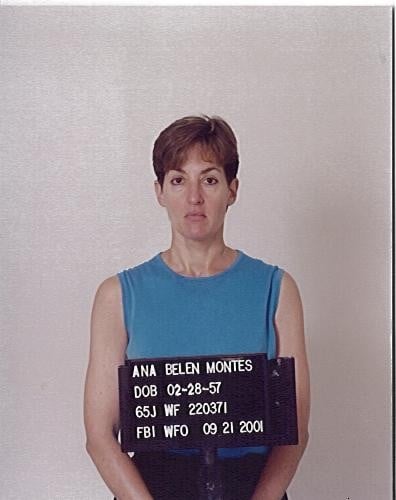

For 17 years, Ana Montes was a diligent employee of the Defense Intelligence Agency, the US military’s spy arm. By day, she was its top Cuba analyst, with access to some of the nation’s best-kept secrets. By night, Montes passed those secrets to the Castro regime: the identities of American spies, details of a crucial surveillance satellite. Until her arrest in 2001, Montes was perhaps the most effective spy Cuba ever recruited, and—according to Jim Popkin’s rollicking new book, Code Name Blue Wren—the most dangerous female spy in American history.

In Code Name Blue Wren, Popkin tells a DC story. Born to Puerto Rican parents, Montes grew up outside Baltimore, attended UVA, then, in 1979, moved to Washington to work for the Justice Department. In 1985—after her recruitment by Cuba—she found a job at the DIA. Outside of work, Montes would hole up in her Cleveland Park condo to decrypt shortwave radio broadcasts from Havana, or meet her handlers for dim sum across Upper Northwest, growing isolated and paranoid as her double life progressed toward arrest. Now, after 21 years in prison, Montes is scheduled to be released this week. We spoke with Popkin about his book, the Washington spy scene, and what to expect when Montes gets out.

How did you first get interested in Ana Montes?

This story has fascinated me for years now. Ana rose up the ranks within the Defense Intelligence Agency and kept getting promoted and promoted—but the whole time, for nearly 17 years, she was secretly spying for Cuba. To me, that would be interesting enough. But on top of it, she had four family members working for the FBI. That includes her sister, Lucy, a translator who coincidentally was assigned to a unit that was dedicated to finding Cuban spies.

One of the reasons that I got into this is that one of my best friends, my college roommate, lived at 3039 Macomb Street. So as a younger person, I hung out there a lot. And after Ana was arrested, he reached out to me. He’s like, Do you realize she bought our condo? The exact unit, she bought it from him. That’s what got the story in my head. This spy lived in an apartment where I’ve been.

Right, and that apartment is important to the story—she’d do her work for Cuba there, then cross the street to call her handlers on the payphone outside the zoo.

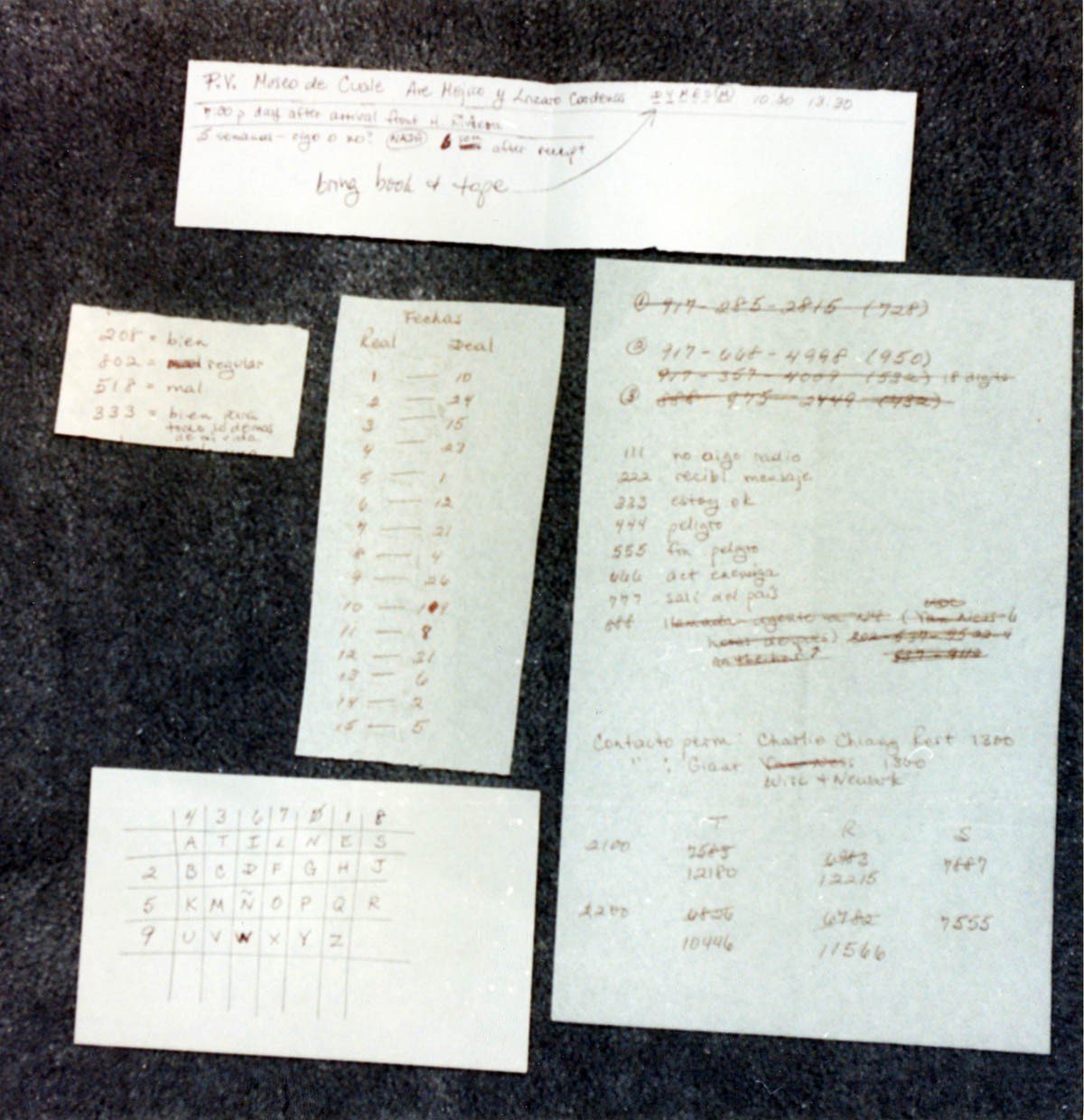

Yes, she was in and out of all those shops on Connecticut Avenue in Cleveland Park. And she was trained in Havana on counter-detection, so she used the zoo to try to evade detection—she would go in and double back to see who’s watching. That’s a classic maneuver to see if someone’s following you. You’d think she was just browsing and looking at animals, but she wasn’t. Then she’d make a call on a payphone to the Cubans with pre-programmed codes.

Backing up, how was Ana initially recruited to spy for Cuba?

Ana was radicalized in college, her junior year abroad, living in Madrid. She fell for a guy from Argentina, sort of a political revolutionary, and she became outspoken in her views about—in her words—US atrocities overseas. Then she entered [Johns Hopkins’ School of Advanced International Studies], and one of her classmates—another American woman of Puerto Rican descent, Marta Velazquez—heard her and befriended her. Marta, it turns out, had already been recruited by the Cubans. So she encouraged Ana.

The Cubans have a brilliant intelligence service. They were trained by the Soviets. And one of the things that they did early on was to get Ana to write an autobiography. Once she did that, two things happened: One is that it was collateral the Cubans could use against her if she ever tried to get out. Number two, they now knew what buttons to push, because they kind of understood her psychology, more than they would have otherwise. And so they were able to manipulate her—play up to her desire for grandiosity and her desire to serve a greater good.

How did she get away with it for so long?

Ana is really smart. She was really good at what she did, and extremely careful. If you look at some of the other major spies—Rick Ames at CIA, he lived beyond his means. And Robert Hanssen took hundreds of thousands of dollars from the Russians, and would hand off classified documents to them in parks in Virginia.

Ana didn’t take those risks. She memorized virtually everything. She almost never took a document out of the building, with a couple very limited exceptions. And so that protected her. She had a day job at DIA, and then her night job was to come home, type up everything she’d seen that day into her encrypted Toshiba laptop, and then, every few weeks, she would hand off a disk to her Cuban handler, who she would meet in restaurants in DC. So that part was risky, but she was just really smart and kept her head down. And there was not that much suspicion about her until much later in her career.

How did she ultimately get caught?

The National Security Agency had gotten information that helped them decode shortwave radio transmissions from the Cubans. They kept referring to an “Agent S,” and so [the NSA] put everything together and concluded that “Agent S” was probably a fairly significant official within the US intelligence community.

They took that information to the FBI, but [the FBI] really spun their wheels for a long time. They thought it was a man, they didn’t know which agency [the person belonged to], so they didn’t get anywhere for over two years. Then an analyst at NSA got really frustrated—she thought that the FBI wasn’t moving fast enough—so she went behind the back of the FBI, and took [the information] to DIA, which was Ana’s actual agency. They figured out very rapidly that this spy had to be Ana Montes.

Some of my favorite stuff in the book involves the logistics of spying in DC.

Yeah, I just love the spy-versus-spy stuff that happens behind the scenes throughout Washington. I used to run around the Russian embassy, and one day, the sun was beaming like a flashlight into the house right across from the embassy on Wisconsin [Avenue]—that house is still there, and subsequently, people started calling it the Spy House. But at the top, there were three skylights. And during the day, you couldn’t see this, but as the sun set, you could see there were three cameras on tripods. And they were directed at the front door of the Embassy.

I love this stuff. This is DC. It still goes on. We spy against our enemies, and some of our friends. They return the favor to us.

Ana Montes’s spying seems to have been concentrated in Upper Northwest. Is that still where DC-based spies are congregating today?

There are spies on both sides of the ledger all over DC. But it’s going to be with a focus on the Russian embassy, the Chinese Embassy, the Iranian mission—you know, the obvious targets. It used to be Iraq as well. This is happening constantly here, but you’re not going to know it when you see it. The FBI is really good about using undercover vehicles and people that you would never ever suspect—people with beat up cars and pizza trucks, people who look like UPS drivers. They just blend in with woodwork. You’d never know they’re there.

What will happen when Ana is released?

Ana gets out this week. Her official release day is Sunday, but her family believes she’ll probably get out on Friday. My understanding is that Ana likely will go to Puerto Rico where she has sympathetic family. And there’s also a small but vocal community of Puerto Ricans who support Cuba and revolution and have been in Ana’s corner ever since she was arrested. My hunch is that she will go to Puerto Rico to get her bearings and restart her life.

She’s on probation for five years under very strict restrictions. I think she’s going to be very careful about what she does. She’s been living in one of the toughest prisons in the country for women. She will not want to return to that environment. I write in the book that she did not get the Martha Stewart treatment at all—she’s done hard time for 21 years.

Ana spied because she thought US policy was immoral. Does she still think she was right?

To this day, Ana is not remorseful about what she did. She believes in what she did and the politics behind it.

Sometimes it’s morally justified to break the law in service of something you believe in. How do you see that in her case?

What the US has done—US foreign policy, especially going back to the 60s and earlier—a lot of it is inexcusable. But I think you could argue that [her conduct] was immoral. If she had a problem with American foreign policy, she had other options. All Americans do. She could protest, she could join an organization, she could write letters. The answer should not be to join an organization, lie through your teeth, and deceive your colleagues and your family to achieve your goal.