The minister’s sermon was about love.

I hadn’t yet packed my bag for the hospital, and I was scared

and a bit hung over from the mojitos I’d consumed the night before. Church

has always been a hopeful and welcoming place for me, and that morning I

needed to be held in grace. I looked at the bulletin, and the sermon title

made me grit my teeth—“The Unspeakable Gift.” In a few hours I’d be

checking into the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda to participate

in a weeklong medical study. My mind was too preoccupied to worry about

love.

The sermon started with a poem by Raymond Carver, “Late

Fragment”:

And did you get what

you wanted from this life, even so?

I did.

And what did you want?

To call myself beloved, to feel myself

beloved on the earth.

The minister, Mark, continued with a reading from St. Paul’s

letter to the Corinthians: “Thanks be to God for his unspeakable

gift.”

The message focused on our ability to give and receive love.

Mark explained that our capacity to love is one of our most precious. He

related the story of a friend who would end a conversation by saying, “I

love you. Do you know how much I love you?” (Who says those

words? I thought.) Mark spoke about the fact that the words made him

feel weird and that it wasn’t until his friend’s death that he really

grappled with their meaning.

Not feeling particularly lovable or loving that morning, I

tried to allow the message to wash over me, seep into my sadness, and

change my heart a bit. I sat there numb and weepy. The service ended, and

I headed home to pack.

I had known about the study for years and ignored the quiet

voice that said the road forward leads through NIH. Then a few years ago,

I was in a class at the Writer’s Center in Bethesda and did a short

assignment about being 15. In the process of researching it, I learned

about the study. I turned the story in and thought that was

that.

I lived five miles from where some of the most renowned

scientists in the world were studying people like me, but I chose denial

and fear—until something clicked and I knew I had to live

differently.

• • •

The journey had started when I was 15. My first menstrual cycle

had been excruciating, and that had set in motion a series of doctors’

appointments. Finding answers meant that my parents and I became private

investigators in a search to make me well. My blood was sent to lab after

lab. At 15, I learned the languages of endocrinology, genetics, and

high-risk gynecology.

Sleuthing and vials of blood led to a diagnosis of Turner

syndrome, a genetic condition in which a female is missing all or part of

her X chromosomes. (Females generally have two X chromosomes, males an X

and a Y.) The syndrome occurs in one of every 2,500 live female births.

Ninety-eight percent of fetuses with Turner syndrome are miscarried. The

syndrome usually manifests itself in extremely short stature and

infertility. It can also mean heart and kidney problems, cognitive

difficulty, spatial-reasoning issues, hearing loss, dry eyes, diabetes,

and osteoporosis. My case was a bit more complicated in that I was missing

only part of an X chromosome, which meant I had a “mosaic” form of the

disorder.

I’m not sure if my endocrinologist had ever made a

Turner-syndrome diagnosis before. His reaction was one of both concern and

curiosity. I remember him saying, “By the time this is an issue for you,

who knows what technology will be able to do?”

After we left his office, my mother and father took me to a

Mexican restaurant. Maybe they were as scared as I was, but we didn’t

discuss what the doctor had said. I ordered a burrito and soldiered

on.

A mosaic form of a genetic disorder allows doctors to hedge

their bets. They’re never really sure how the condition will express

itself until they poke around inside. My endocrinologist wanted to find

out exactly what Turner syndrome looked like in me, so he sent me to a

gynecologist who was known to handle unusual cases.

A laparoscopic procedure, which required general anesthesia and

a small incision below my belly button, confirmed that I had “streak

ovaries” (scar tissue that doesn’t produce eggs). A bone-density scan

revealed that at age 15 I was already on the road to osteoporosis. I

wanted to be thinking about guys and driver’s ed, not bone degeneration

and ovulation.

The years that followed were filled with treatment typically

prescribed to postmenopausal women—hormone-replacement therapy,

bone-density scans, bone-strengthening drugs. As my doctor tried different

hormones, I endured the same emotional shifts, night sweats, and weight

gain familiar to many grown women. I never looked any deeper into Turner

syndrome than the initial investigation. I even kept the same gynecologist

until I was 33, scheduling appointments months in advance and making

special trips home to Louisville from Washington so I wouldn’t have to

explain my situation to anyone.

I grew weary of educating doctors about Turner syndrome when I

was being treated for everything from strep throat to pinched nerves. The

question about medications always required that I disclose

hormone-replacement therapy, which meant I had to explain why someone of

my age was taking hormones.

Disclosure became more complicated once I became an adult and

health insurance entered the picture. When asking about preexisting

conditions, an insurance investigator once said, “When did the condition

start?” and I replied, “Mitosis.”

A pause, then the follow-up: “When do you expect treatment to

end?”

“When I die.”

Again and again, I cringed at the thought of coming out as a

person with Turner syndrome. I tried to retreat into a kind of normality

that deflected reality as much as possible.

The decision to participate in an NIH study was an attempt to

confront the silence. I was 35 years old. It was time.

• • •

I arrived at the NIH Clinical Center alone, early, and

unprepared. The nurse responsible for checking me in wasn’t even on duty

yet. I had packed my suitcase as if for a four-day business conference,

not a hospital stay—slacks, blouses, and pumps rather than T-shirts,

sweats, and tennis shoes. That was probably a function of my denial as

well as my “don’t leave home without lipstick” impulse. I’d never spent a

night in a hospital, never had an MRI or CT scan.

People generally don’t go to NIH when they have a

garden-variety illness. NIH takes the sickest of the sick and offers hope.

Old and young gather there. The common denominator is illness—the kind so

serious that it generates platitudes and whispers. To be a patient at NIH

feels like being a contestant on a reality show in which all the cameras

are turned on you—or being a lottery winner when the prize is assuming a

large debt at a huge interest rate.

My mom arrived from Louisville that evening to hold my hand.

She had gathered some hospital-friendly clothes from my apartment in

response to my SOS call and set up my closet while I tried to make sense

of my hospital schedule.

A nurse came by and pointed out the container into which I’d

need to pee. She told me they’d be taking my heart rate and blood pressure

every few hours. She noted the times I’d need to fast and the times they’d

be drawing blood. She said the study director would arrive in the morning

to make sure my paperwork was complete. She revealed very little, other

than time and location, about the alphabet soup of tests on my schedule:

“The specifics will be explained by the doctors.”

All my meals would be in my room. I shared the first one with

my mom. The food looked like it was supposed to taste good. I had been

assigned the least restrictive diet and could eat as much as I wanted when

I wasn’t fasting. I ordered enough for two, and my mother and I sat there

talking about her trip and what the nurse had described. After dinner, she

headed to my apartment.

While we were eating, my roommate, Annie, arrived. Roughly my

age, she was the first person with Turner syndrome I’d ever

met.

Annie was from Texas, where I’d gone to grad school, so we

talked about barbecue and line dancing. At five feet, she was a shade

taller than I was, with wavy red hair hanging down her back. Her disarming

drawl and openness stood in opposition to the short sentences and hard

edges that would characterize my time at NIH. Before I met her, my image

of Turner syndrome was based on pictures in 1950s textbooks of people who

looked like a cross between Dawn of the Dead zombies and

Frankenstein. She was beautiful.

I had someone to talk to during the nights that would prove

difficult. Annie was in love, and we spent hours talking about the

wonderful man with whom she planned to spend her life and who was

supporting her through the Turner-syndrome journey. I wasn’t in a

relationship, so her story was a hopeful example of love and connection.

The study occurred in September and I was planning a trip to New Zealand

in November, so she listened to me talk about my plans as I thumbed

through my Let’s Go and Lonely Planet guides.

Annie had participated in the study three years before and was

now doing the follow-up longitudinal component. Doctors had found problems

with her heart during her earlier stay, so a great deal was at stake. She

knew the ropes and could sometimes assuage, sometimes confirm, my

fears.

Most of all, we shared a bond that widened my circle of what it

meant to be normal. She knew what it was like to have the “So . . . let me

explain about my having children” discussion with a boyfriend. She knew

about hormone-replacement therapy and what it was like to hear a doctor

say, “Well, your aorta could be malformed and your kidneys could cease

functioning.” She had osteoporosis, and clothes didn’t really fit her,

either.

I met the principal investigator (PI) of the study on Monday.

Her salt-and-pepper hair and wire-rimmed glasses projected deep knowledge.

Very scientific, she discussed the history of the study and explained how

it fit with other Turner-syndrome work around the world. She had a

perpetual-motion air that didn’t seem to allow her to sit down and hear my

story.

I quickly learned that my experience wasn’t the point of the

study. Doctors were primarily interested in the clinical and genetic

factors related to Turner syndrome. The PI talked about an additional

study on blood glucose in which I’d be asked to participate. Our eyes

never really met. My mom took notes. The PI was politely interested and

left after ten minutes. Her assistant provided copies of articles

published by the NIH research team.

The first major procedure during my first full day at NIH was

the insertion of a PICC (peripherally inserted central catheter) line—a

thin tube that runs under the skin from the arm to the heart. I chose to

have the PICC line so as not to be stuck with a needle every time someone

needed to draw blood or administer a substance during a test. (Quite a

choice.) PICC lines are generally used for the long-term administration of

chemotherapy or antibiotics.

I went to the PICC area and signed more papers while someone

talked very quickly about what the papers said. Then I was escorted to the

sterile room where the line would be inserted. The Today show was

on a TV in the corner. I watched a segment about Paris Hilton as they

administered a local anesthetic and began to search for a

vein.

The nurse, an athletic thirtysomething guy, said, “I’m glad

you’re nice. This is the first time I’m doing this, so you might have to

be a little patient.” He laughed, and my heart sank, unsure if he was

joking.

Inserting the line involved inching a small tube toward my

heart. It slithered through the muscles of my upper arm, pointing toward

my chest, where blood flowed freely. Centimeter by centimeter, the

technician charmed the snake toward its destination. (I felt nothing.) He

checked the placement, made sure I was “responding correctly,” explained

cleaning procedures, and sent me on my way. The line would remain in for

the duration of my stay.

I wandered through corridors and elevators—around silk ferns

and muted sofas positioned for comfort and community—trying to find my

room. I thought of the direct line to my heart that now existed. If only

it were that easy to make way for emotions to move and dance, for the

substance of grief and pain to flow in and out, for memories to live and

transition to some higher place.

In elevators and waiting rooms, I witnessed the frailty of the

human body—bald children with defeated eyes, families speaking in somber

codes. I saw a man gently holding his wife’s hand as she rested her head

on his shoulder. A child of no more than eight walked up to the reception

desk and relayed information with the swagger of a surgeon. He shouldn’t

have had to be that smart. I saw old people present file folders the size

of encyclopedias to nurses. I saw infants staring at mortality. We were

all on the same road, traveling at different speeds.

• • •

On my third day, I had a 3-D cardiac MRI. Like the entrance to

a dragon ride at a carnival, the rolling, bed-like platform takes you into

the mouth of the beast. I walked into the room, and the nurse—who looked

as if she could run a marathon in two hours—asked about buckles or other

metal on my clothes. She handed me a headset-like contraption to mitigate

the loud noise. I’d be inside the machine for an hour while the doctor

administered the test, which would produce a three-dimensional movie of my

heart’s activity. The doctor arrived and the procedure began. The sound of

the machine was deafening, and I seemed to lie there forever.

The movie my heart produced—part video game, part Discovery

Channel—was brief. I saw my heart beating on a small screen. Muscles moved

with the fluidity of a ballet dancer. Blood flowed like a river. Valves

opened and closed as elegantly as a bird’s wings. The components of my

heart worked together in such a way that I left convinced of a God. The

experience of seeing a 3-D film of my heart was intimate and distant,

natural and artificial.

The cardiac MRI was one of many tests focused on my heart. The

heart is one of the primary organs affected by Turner syndrome, so it

received a thorough evaluation. The knowledge that this organ would get a

tremendous amount of attention was one of the primary reasons I’d been

scared to participate in the study, but I knew I needed to do it. Every

inch of the grand muscle was checked for shape, strength, and

function.

I had lived my entire life not knowing my heart. Finishing a

marathon seven years earlier hadn’t convinced me it was healthy. My family

history of cardiac disease surrounded my heart in a shroud. I can’t

describe the relief on the face of the technician who broke the rules

(only doctors are supposed to reveal test results) and told me my aorta

had fully functioning valves or the affirming nod by another one who read

my EKG. I can only say a weight in me was lifted with each revelation.

Textbook pictures of malformed hearts no longer matched mine. The

premature deaths of family members were countered with each piece of

positive evidence.

• • •

On my third afternoon, I reported to radiology for a pelvic

ultrasound. Pregnant friends had described this test and shared

black-and-white images of life as it grew inside them, so I went in

knowing a little about what to expect. The technician, a stern woman,

instructed me to take off my shirt and pants and put on the gown. I sat on

a bed and watched her prepare the jelly that had been warming in a

toaster-oven-like appliance. I was truly excited. She asked me to lie down

and moved my gown to the side.

The technician rubbed the warm substance across my belly and

moved a small implement firmly over me from left to right. I watched her

slow, steady hands and thought about the fact that I now shared something

with friends who were mothers. For a moment, I felt as if I were joining

the sorority of women who could have babies.

She gently pushed the instrument, and I prayed that things

could be different. On the screen, I saw a large, empty space that I think

was my uterus. The technician said, “The doctors will provide analysis of

the images later.”

Happiness turned to grief as I contemplated the truth this test

would likely confirm: the scar-tissue ovaries that had been revealed years

earlier. The test ended, and the technician left. I wiped off my stomach

and dried my eyes. I lay on the table for a few minutes, thinking about

how different this experience was for most others.

How do I negotiate being fully female but somehow not? I felt

as though a fundamental choice—the decision whether to have children—had

been taken from me. I never got to weigh the pros and cons, dream about

baby names, or anticipate pointy elbows and knees protruding from beneath

exhausted ribs.

My diagnosis had forced me to approach the question of children

not as an easy assumption but as a challenge I’d confront later—when

technology would make pregnancy possible or adoption would bring children

into my life.

As I sat in that room, the issue no longer swirled in my head

as an abstract concept to contemplate in the future. A visceral grief

settled in my bones. I lay there breathing and crying, hearing the

deafening silence. I was cold and lonely. Emotionally bare, I prayed to

understand how I could love myself if I was never a mother. I prayed to be

whole, to feel the grief that I had buried for so long.

Somehow I gathered myself enough to put my clothes on and move

on to the next test. To say I found resolution would be a lie. I still

struggle with the feelings that surfaced in that room every time I

consider motherhood.

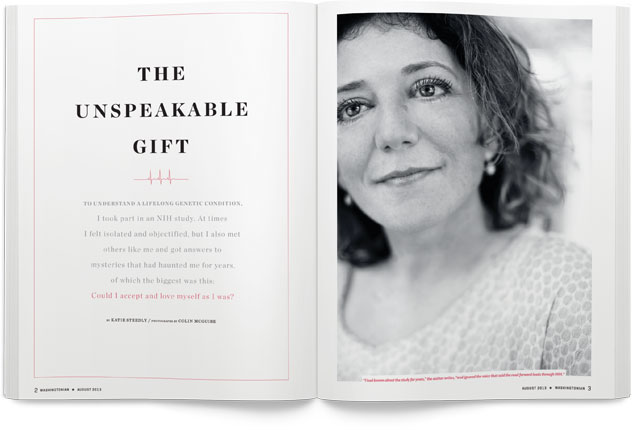

The study required that photographs be taken of me. I don’t

like having my picture taken in the best of circumstances, and I was angry

at being subjected to a camera’s eye.

The experience reminded me of the pictures of women and girls

with Turner syndrome I had seen over the years. I couldn’t help but think

about the grotesque pictures of females with the condition that appeared

in textbooks, depicting abnormal bodies, webbed necks, malformed hearts,

horseshoe-shaped kidneys. The subjects were never smiling; they were

simply ugly. I was now being forced into an experience similar to what I

imagined they had endured.

I couldn’t look at the photographer when I entered the small

room. He seemed nice enough, but my mood was such that I resented the very

oxygen he demanded. He asked me to remove my shirt but let me leave on my

bra, camisole, and jeans. (I was relieved beyond belief.) The fluorescent

lights made my skin appear corpse-like.

I was to stand in front of a screen and let my arms hang, not

allowing my shoulders to tense up and curl forward. The photographer said

he was particularly interested in the way my elbows extended. He didn’t

give me instructions for my face, so I’m not sure it was included in the

picture. He asked me to turn to the left and remain relaxed. (It’s really

hard to relax when someone requests it.) I turned to the right. He came

closer for what I assume were close-ups of my face and neck from various

angles. I wish I’d been clever enough to think of an expression that

passive-aggressively said “F— you” or that subliminally said “Really see

me” to everyone who would look at these pictures in the

future.

The photo session put me in touch with an anger I hadn’t been

able to articulate. I was angry that I just had to stand and have pictures

taken of me. I was angry that I was hungry and hadn’t been able to eat

because I’d had a blood test that afternoon. I was angry because a nurse

had tried to stick me with a needle at 5:30 in the morning. I was angry

that I had Turner syndrome. I was angry that I was different. I was angry

that there was no cure.

• • •

One of the final tests on my last day was a comprehensive

hearing exam. The audiologist looked as if he’d stepped out of a J. Crew

catalog, and he had an empathetic demeanor. We had a long discussion about

the connection between Turner syndrome and hearing loss. He asked me a

battery of questions, then handed me a buzzer and stood in front of what

looked like a rock-music soundboard.

The test was easy at first. I was told to press the buzzer when

I heard a sound. I detected a variety of sounds at a variety of pitches

and volumes. As the test progressed, there were centuries of silence. I

got a sick feeling and began randomly pressing the button—like choosing C

on a multiple-choice test when you have no idea of the answer. Every once

in a while, I actually heard a sound. I couldn’t tell what pitches or

volumes were more audible. I knew in my gut I was failing.

After the test, the audiologist printed the results and told me

I had significant hearing loss within the pitch range of the human voice

and explained this was common for Turner patients. He suggested I consider

hearing aids.

A wave of fear washed over me, and tears welled. I had been

through so much, and now this information pushed me over an edge I didn’t

even know I was near. Somehow I heard the news as more evidence that I was

less than whole. I thought about all the ways in which I was imperfect or

broken, about every time I’d asked for clarification when someone spoke or

nodded in agreement when I hadn’t heard something, about my need over the

last few years to see people’s mouths when they talked—all the

subconscious coping mechanisms I’d developed. Being flawed had now been

scientifically verified. I knew hearing aids wouldn’t make that feel any

better.

• • •

The study culminated in a conference in which the research team

would come to my hospital room and share my results with me. I had my PICC

line removed that morning and would be released after the

meeting.

My mother and I were waiting, a mixture of fatigue and fear

churning in my stomach, when a chaplain came to the door. She had been

ordained in the same denomination in which I’d grown up, the United Church

of Christ, so our theological waters converged immediately. The chaplain

asked about my story and shared her own—she had a social-justice

background that had taken her around the world, and she was new to NIH.

She asked if my mother and I wanted her to pray with us. We said yes. (We

were both exhausted from the week—my mom had spent every day with me,

leaving only to sleep at my apartment—and scared about the final

conference.) After about 15 minutes, the chaplain held our hands and asked

that the God of health and safety watch over us. She affirmed the fullness

of God’s grace and asked that it be present in our comings and

goings.

Her visit brought a measure of peace and warmth to the clinical

experience I’d lived at NIH. She was a reminder of my faith. She was God

made real in that moment.

After the chaplain left, the research team began to assemble.

One by one, a sea of spectacled anonymity filled my room and a buzz akin

to that of an AM radio in the desert descended. The group of about a dozen

circled as I sat on my bed and listened. My mother took notes. The

principal investigator led the discussion, with analysis by one of the

chief scientists. Their students listened as they explained the results of

my 20 or so tests. They talked about my heart, hormones, bones, kidneys,

blood glucose, blood pressure, eyes, skin, and liver. They concluded that

I was pre-diabetic, had a fatty liver, needed to lose 20 to 25 pounds, had

osteoporosis, and had significant hearing loss.

They wrote no prescriptions. They made no referrals to

specialists. They didn’t seem alarmed by the findings. The atmosphere

seemed strangely relaxed given what my body had endured—they seemed to

have told this story a million times.

I tried to not interpret their lack of interest as cavalier

indifference. I was both relieved and angry. Somehow this meeting didn’t

provide the closure that I craved. I’m not sure what would have—short of

someone saying, “We’d like to enroll you in a genetic-therapy experiment

in which we’ll correct your chromosomes. You’ll grow six inches, and your

ovaries, ears, and bones will be fixed.”

I know that wouldn’t have satisfied me, either. I think I

yearned for acknowledgement of who I was and for the knowledge that

emerges when the body is examined to the degree that physical truths are

revealed and our understanding of ourselves is changed. The NIH doctors

weren’t concerned with what I’d learned or experienced. That wasn’t their

job.

I left bruised and a bit lighter. Years of silence had been

shattered: I’d met my heart and confronted the grief I felt about my

fertility issues. Somehow normal grew to include me.

• • •

I’d never again wonder if my aorta allowed blood to flow in the

right direction (it does) or if my bones were as thin as lace (not quite,

but I have to take calcium and vitamin D supplements). I learned that my

eyes produced enough tears. I received answers to long-held questions

about my physical state. I learned I was strong enough to ask questions. I

learned that being whole is a complicated journey that starts with

breaking our silences and learning to love the parts of ourselves we fear.

I wanted to start more conversations, continuing and expanding the

spiritual and psychic excavation that began within those stark

halls.

I’d have a conversation with my minister in the courtyard of my

church, on the stone benches where I’d passed hours. I wanted to ask him

about the relationship between loving oneself and being loving in the

world.

He might say, “Being loving in the world starts with loving

oneself.” Or he might talk about Martin Luther King Jr. and invoke the

idea that real love takes courage—the kind of which peace, compassion, and

reconciliation are born—and that loving oneself is a profound act of

courage. He might invoke poet Mary Oliver and remind me to “let the soft

animal of [my] body love what it loves.” I would then ask him why St. Paul

called love the “unspeakable gift.”

I’m not sure how he would answer. I think he would talk about

how hard it is to love sometimes, and that the ability to love, even when

it’s hard, is a gift.

I would have a conversation with myself at age 15. I hear this

conversation as clearly as the sea knows the tide and the sky knows the

sunrise. We would meet by the tallest tree in the back yard of the house

where I grew up. My 15-year-old self would be wearing her Rocky’s Sub Pub

uniform and pounds of blue eye shadow. I would tell her everything was

going to be okay. I would show her the NIH results and explain how they

describe her but don’t define her. I would tell her it’s all right to be

mad as hell. I would stroke her hair and tell her she’s beautiful and

whole. I would hold her and explain that she could be a world traveler,

fearless warrior, and loving spirit.

Then I’d have a conversation with myself at 80. We would sit on

the porch of her mountainside home. She would offer me something to drink

and I’d ask for sweet tea. Her long, wavy gray hair would be gathered in a

bun. I would ask why it took me 20 years to find out about Turner

syndrome’s effects on my body. I’d say, “Why was I so scared?”

“We come to things when we are ready,” she’d say.

I’d ask, “How would I live my life differently if I really knew

I was whole?”

She would respond with questions: “Don’t you love completely?

Aren’t you guided by your passions even when that path is difficult? Do

you frame each day in gratitude? Don’t you act generously with loved ones

and strangers?”

Then she would say, “Being whole looks like that.”

She might even hold my hands in hers and add, “I love you. Do

you know how much I love you?”

Katie Steedly (author@katiesteedly.com) lived in Washington

for seven years. She currently lives and writes in

Cincinnati.

This article appears in the August 2013 issue of The Washingtonian.