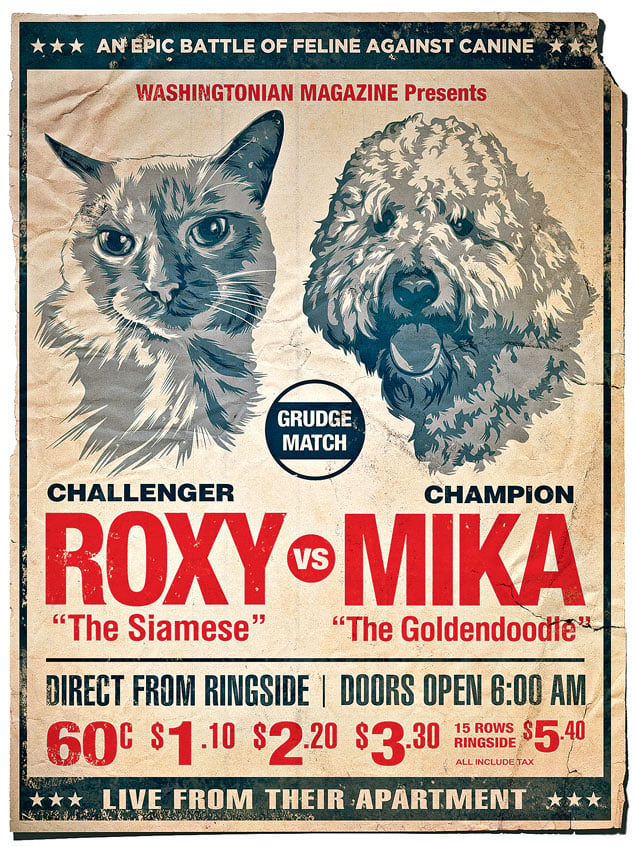

When my husband, Ben, and I brought home our dog, Mika, a curly-haired 1½-year-old goldendoodle, I was anticipating the usual headaches of dog ownership—chew marks on my most expensive boots, whining at 3 am. What I didn’t expect was terrorizing our lazy 14-year-old Siamese cat, Roxy.

I’d grown up with Burmese cats and golden retrievers, and they’d always gotten along. Why would this be different? For one thing, we live in an 800-square-foot apartment in Logan Circle, not a house in Bethesda. For another, Roxy is declawed. And last, I didn’t realize we were violating one of the cardinal rules of dog/cat relations: When choosing a new pet, match a young cat with a young dog, high energy with high energy, lazy with lazy.

We were trying to make Miley Cyrus get along with Maggie Smith.

Ben and I read up on the best way to introduce dogs and cats (keep them separated, let them figure each other out at their own pace), but quickly a toxic cycle began: Roxy would hop off whatever dresser she was lounging on. Mika would spring up—even from a nap—stiffen, and bolt after her. Although one of us usually managed to catch Mika before she reached the cat, there were times we’d find Roxy pinned on her back by Mika’s paw, hissing and growling. Mika wagged her tail as if she’d won the most fun game ever.

When Roxy started confining herself to a closet and dropping weight, we knew the “let them figure it out” thing wasn’t working. We tried obedience classes. Our vet put Mika on Prozac for five months. We tried to distract Mika from Roxy with what the trainers call a “Ferrari-level” treat (Frosty Paws ice cream). We sprayed Mika with a water gun whenever she went for the cat. We tried teaching her to ignore the cat by rewarding her with treats whenever she responded to the “leave it” command. The only change: Mika was getting chubbier from the constant flow of bison jerky and peanut-butter ice cream.

“Some dogs and cats just weren’t meant to be together,” the vet told us.

By the time trainer Michelle Yue of Good Dog DC came over, we’d become resigned that the animals would probably have to lead separate lives within our apartment.

Yue’s philosophy: Stop bad behavior before it starts. If the dog’s energy level ramps up to 11 on a scale of 10 whenever the cat comes around, our goal is to keep her at 1. I also appreciated that Yue was realistic. “You can do this when you’re watching TV,” she said.

Yue outfitted Mika with a head collar called a Gentle Leader—a painless nylon collar that fits around her head and snout and allows us to exert pressure on the back of her neck so she isn’t choked—and put her on a leash. “We’re going to teach Mika that it’s her job to lie down and stay when the cat is around,” she said. The trick was to make it into a mental exercise for the dog by letting Mika decide to do it: “You want her to figure out that lying down is what she needs to do to be comfortable.”

Yue pulled the leash taut, and Mika thrashed around. After a few minutes, the dog lay calmly on the floor. Yue took out a toy and placed it a few feet from Mika. Whenever she jumped for it, Yue tightened the leash and Mika went back down.

We’re a few weeks into training with this method—inside the apartment, we’ll gradually transition off the Gentle Leader, then off the leash—and we’ve seen more progress every day than we have all year. I’m not sure we’ll ever feel comfortable leaving them in the same room together when we’re not home, but last night Mika and Roxy sat in the bedroom four feet from each other for a good hour. I’m not sure the war is over, but I think we’ve reached a détente.

This article appears in the March 2014 issue of Washingtonian.