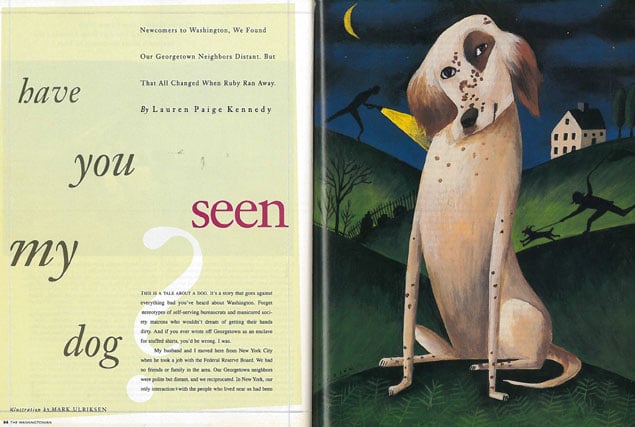

This is a tale about a dog. It’s a story that goes against everything bad you’ve heard about Washington. Forget stereotypes of self-serving bureaucrats and manicured society matrons who wouldn’t dream of getting their hands dirty. And if you ever wrote off Georgetown as an enclave for stuffed shirts, you’d be wrong. I was.

My husband and I moved here from New York City when he took a job with the Federal Reserve Board. We had no friends or family in the area. Our Georgetown neighbors were polite but distant, and we reciprocated. In New York, our only interactions with the people who lived near us had been a broom handle to the ceiling and a shout of “‘Turn it down!” Washington wasn’t an easy adjustment. We were lonely. Then it came to me: Get a dog. We weren’t ready to start a family, but perhaps we could gain comfort and expand our nest by rescuing a soul in need.

Ben and I went to the Friends of Homeless Animals of Northern Virginia in Loudoun County on a Saturday afternoon. Every dog there was a walking tragedy. Choosing one was nearly impossible, but the minute we saw Ruby a white-and-liver-spotted English setter—we wanted her.

Abandoned in the Virginia woods, Ruby was a survivor, albeit an abused and damaged one. She trembled, tucked her tail, cowered in her kennel, and shied away from people. We vowed to revive her joie de vivre, certain that she would, in turn, revive ours.

Ben dreamed of training Ruby to run at his side in Rock Creek Park. As for me, a maternal instinct I’d never known kicked in. When Ruby had nightmares—whimpering in her crate and beating her tail—I lay on the floor in the dark and stroked her. I whispered that we would never let her down. I promised she would never be hurt again.

That makes it twice that I was wrong.

• • •

It was Thursday, April 19. We’d had Ruby eight days, and she was showing progress. That morning she’d wagged her tail and licked my hand.

As I opened the door to take her to the park, a WET PAINT sign greeted me at my front steps—a surprise from the condo’s maintenance staff. Ruby charged forward, her pink paws staining black as I tried to pull her back. She looked at me, confused. Just then my neighbor, a bear of a man named Jim, approached us. As I tried to keep Ruby from the paint and close the door, he offered to help.

Something about Jim triggered terror in Ruby. She reared up, squealed, wriggled out of her leash, and darted into R Street. An SUV screeched to a halt. My heart stopped. Then I heard a thump. I ran into the road, scanning it for Ruby’s body. My eye caught a blur of white streaking across Montrose Park toward the tree line that signaled the start of the woods.

“Ruby!” I screamed. All of my trips to the gym and daily jogs failed me. Even injured, Ruby was too fast. I tailed her into Rock Creek Park, then lost her as she rounded a path. I cried her name again. Then I fell down in the dead leaves and sobbed.

• • •

Two hours of searching passed.

“You’ve got to poster the area immediately,” Officer Scotlund Haisley of DC Animal Control told me. With spiky hair and wraparound sunglasses, Haisley looked like a surfer in a cop’s uniform, but his furrowed brow suggested that his job was no day at the beach. “Blanket the woods before the evening joggers come out. Put her picture on it. Run to Kinko’s now. I’ll keep looking.”

Forty-five minutes later, I was taping a poster to every sign, park bridge, and large tree within a mile of where Ruby had disappeared. I called her name and squinted for a moving white mass among the underbrush. Was she dying somewhere, licking her wounds?

I returned home to find Haisley waiting for me.

“We need to set a humane trap,” he said. “Bait her with some food. Let me get that organized.”

He’d barely finished his sentence when he was called uptown to pull apart two pit bulls.

“I’m so sorry,” he said as he left. “There aren’t enough of us to go around, and pretty soon there won’t be any. The city hasn’t renewed our contract, and we’re the only game in town. Unfortunately, I get too many calls for dog fights and too few from pet owners who care.”

He left his card. “I’ll check in later, and I’ll come back tomorrow with the trap if you don’t find her tonight. Hell, if you do and it’s 3 AM, call me at home. I want to know.”

• • •

The posters had barely gone up when the neighborhood started buzzing.

Georgetown is dog country, and Montrose Park is ground zero for an assortment of mutts and their owners.

A lost dog was serious business, an injured one a state of emergency. That night Ben and I were stopped by more than a dozen strangers who vowed to search. Many mentioned another dog, Montrose—named for the park—that once had all of Georgetown talking.

Montrose had been a dumped stray who feared humans. He lived in the woods for months, surviving on scraps from behind the Safeway and the occasional dead animal. He arrived every day to consort with the park’s other dogs, playing as long as people remained at bay. The minute anyone approached, he took off for Rock Creek. He became the park’s unofficial mascot and a neighborhood legend.

“It took many, many attempts,” said Justin, the man who eventually adopted Montrose. “One time we set out a big steak on a blanket. The plan was to wrap Montrose in the blanket when he started eating. That dog was just too smart. Twenty other mutts ran for the T-bone, but Montrose hung back. He knew what we were trying to do.”

“So how’d you catch him?” Ben and I looked at Justin as if he were a guru who could guide us.

“Poor guy. A few of us jumped on top of him and wouldn’t move,” he laughed. “It was the only way. I’m just glad we didn’t suffocate him.”

After a struggle, Justin took Montrose home. With a little time and tenderness, the dog came around. Now he was the most famous pooch in the park, a happy guy who loved everyone—and who came when he was called.

Montrose’s story gave us hope.

• • •

Friday morning, an anonymous caller sighted Ruby.

She was seen drinking water from Rock Creek on the Oak Hill Cemetery grounds. She was limping but could still run.

Oak Hill is an exclusive burial place on R Street, open to the public during irregular hours and closed on weekends. Its entrance is across the street from the late Washington Post doyenne Katharine Graham’s mansion. Graham’s husband is buried there (as is Graham herself now). Spiked iron gates and barbed wire keep people out but fail to thwart small animals. The fenced land borders Montrose Park, Rock Creek Park, and another cemetery off Q Street, Mount Zion.

After hearing of the sighting, I entered Oak Hill. The iron gates were open, but a sign read CLOSED FOR A PRIVATE GATHERING. A man with a George Hamilton tan popped his head out of a building. “Young lady, where do you think you’re going?”

It was the caretaker, who lived on the grounds. He wasn’t moved by my tears or by the leash hanging around my neck.

“That dog is not here,” he said. “And no, you cannot come in. This is private property. I have to respect my clients.”

I looked around. “Your clients are all dead,” I said. “My dog could be dying, and she was seen here minutes ago. Surely you can make an exception?”

“Trespass and I may call the police.”

“So call them.” I kept walking. I could feel his glare boring into my back as I continued my search. Wonderful, I thought. Ruby’s lost, and now I have to contend with a real-life Cruella De Vil.

• • •

Saturday morning and still no Ruby.

Officer Haisley set two traps in the woods. Each had a door that would shut after an animal entered it. Both were baited with puppy chow. Saturday afternoon and evening came, and then Sunday morning. We didn’t catch anything, and no sighting was reported.

Ben and I spent the weekend canvassing the trails behind the park, going west toward Whitehaven Street and north past the Massachusetts Avenue bridge. We walked every path, climbed every bluff, scurried down every ravine, treaded through overgrown terrain, waded through streams, and climbed rocks. We plastered the area with Ruby’s picture. Our limbs were bleeding, bruised, and weary. We picked ticks off our T-shirts. I feared the worst.

Still, our spirits were buoyed by the stream of residents who told us they’d seen the signs, called their friends, brought their dogs, and joined the search. I felt humbled by their kindness.

Sunday afternoon we went home for a drink of water. Just before we went inside, former Health and Human Services secretary Donna Shalala stopped us. She lived around the comer.

“Still no luck?” she asked.

We said no.

“Could Ruby be in the cemetery?”

We nodded.

“I’ll get you in,” she said with a determination one might have seen when she was trying to get a new health policy passed. “Be here at six and we’ll go together.”

At six Shalala rang our bell.

“I have a key to the gates,” she said. “Certain members of the community can let themselves in.” She winked. “But I made a phone call to the caretaker to be polite. He’s expecting us.”

Mr. Cruella greeted us warmly, as if the exchange from two days before had never occurred. He sucked up to Shalala immediately and told her he had gone looking for Ruby earlier that day. I coughed.

His real persona surfaced when he said sternly, “Ms. Shalala, you must promise me you’ll escort these people through the property at all times.”

She shot him a look and assured him she would.

We set off for the creek. As the three of us searched, I told Shalala about the plight of DC Animal Control and how it was on the verge of losing its contract with the city. I told her how empathetic and stalwart they’d been. She seemed disturbed. She, too, had a rescue dog.

“What you need are a few bloodhounds,” she said after an hour’s effort yielded no sign of Ruby. “If you can’t come up with anything on the Internet, call me at home. I may have some leads through the FBI.”

• • •

Several sightings trickled in on Monday, but Ruby remained elusive. We had yet to find anyone with bloodhounds and were feeling mentally and physically spent after consecutive ten-hour days in the woods. Someone had given us the number for Marta Williams, an “animal communicator” in California. We were will ing to try anything. I called her.

“How does this work?” I asked Williams.

“You describe your dog,” she said. “I look at a map of your general area. Then I ask my guides to direct me to Ruby. I do astral projection and go to the site where she’s hiding. I find her, look at her injuries, and talk to her. I do energy work with her to try to get her to come home, or at least reveal herself to you when you’re looking.”

“Okay,” I gulped. I described Ruby, hung up, and waited.

Williams phoned me back a few hours later. “Ruby is north of you, toward the Kalorama area,” she said. “She’s terrified of people and is afraid to come home. She definitely has a broken leg—I think it’s her back left one, but I can’t be sure. She knows you’re looking for her, but her fear is too great. She’s near the creek, hiding in a cave of rocks. She’s very hungry. I’m going to keep working with her. You go to Kalorama, near Belmont Road, still beneath the bridge.”

Ben and I set out for Kalorama, parked as directed on Belmont Road, and descended a bluff toward the creek. The Taft Bridge loomed above us. We shouted Ruby’s name, tramped through mud and leaves, stumbled on a dead cat and a homeless person’s makeshift tent.

The sun set and we headed home, dejected. We’d called an animal psychic from California. We were losing it.

• • •

Tuesday morning, I caught a raccoon in one of the traps. The critter was overjoyed by its puppy-chow breakfast. I let it go.

Tracking dogs were key if we were to get Ruby back. There had been one or two sightings in the woods on Monday, but the trail was cold by the time they were phoned in. It was time to call Donna Shalala.

“Of course I’ll help,” she said. “Let me see what I can come up with. By the way, did you see today’s Washington Post? There’s a nice story on the op-ed page about DC Animal Control. Something about the urgency of renewing its contract.”

“Did you have something to do with that?” I asked.

I could almost hear her smiling through the receiver. She’d never tell.

As Shalala was searching her Rolodex for FBI pals with bloodhounds, the phone rang.

“My name is Carl Washington, pet detective,” a man said. “I hear you’re looking for some tracking dogs. I’m the best, ma’am. If your dog’s out there, I’ll find her.”

“Did Donna Shalala send you?” I said.

“Who?”

“Forget it. I’m just glad you called. How soon can you come?”

Mr. Washington arrived from Falls Church 30 minutes later. He looked more Out of Africa than Ace Ventura, dressed in an orange vest, a safari hat, and jeans. Nets and poles were slung around his shoulders.

This real-life pet detective didn’t use bloodhounds. His tracking team consisted of one little poodle and a tiny terrier. They looked like boys sent in to do a man’s job.

“Poodles have a better nose,” he assured me. “And Jack Russells can outrun anything. The poodle picks up the scent, then Jack here chases your pet and circles around her like a sheepdog, nipping at her if she tries to get away. Then I throw the net, and you get your dog back.”

“Sounds good to me,” I said.

“I have a 70-percent recovery rate. I dropped everything when I heard Ruby was injured. I had another case, but a hit dog can die from infection.”

“How much will this cost?” I asked. “If I get Ruby today, I won’t charge you a dime,” he said. “Otherwise, just enough to check my dogs for ticks and fleas, plus any reward you want to give me.”

I felt overwhelmed with his generosity. I said okay. His team sniffed Ruby’s bed, then strained at their leashes to get going. They took off toward Rock Creek Park, pulling Mr. Washington with the power of a large dog pack.

• • •

Wednesday morning, 5:45 AM. A pounding at the front door. Carl Washington was holding an all-night stakeout in the park—he must have caught Ruby! When I opened the door, I saw a short woman and a Great Dane.

“Ruby’s across the street!” she shouted. “I was walking our dog and saw her, right by the fence! Along the cemetery!” She was jumping up and down, pointing. The Great Dane howled. I threw on my shoes and ran outside. Ben followed.

We crept along the fence but saw no sign of Ruby. We trailed it past one of the traps and into the woods. We called her name. We looked for an hour. Nothing.

Upon our return I found a note in the doorway from the pet detective:

“Here until 5:30 AM. Can’t keep my eyes open. Will return later. Don’t worry! We’ ll find her!”

He had missed her by minutes.

• • •

Later that day, Ben was busy riding the learning curve at the Federal Reserve. Inevitably, Ruby’s plight had become water-cooler conversation among his fellow economists.

One of Ben’s coworkers, Bill, devoted an afternoon off to help with the search. He picked up his wife and headed for Rock Creek Park. Within an hour they spotted Ruby. I couldn’t believe it—we had hunted the woods for six days. We had hired a psychic and a pet detective and had come this close to bothering the FBI. Our neighbors had seen her, and now Bill had, too. Why hadn’t we?

Bill said Ruby had scooted up a hill into some underbrush behind Montrose Park and disappeared before he or his wife could grab her. He was certain it was our dog.

“Smallish? Thin? Brown patch over her eye? Dirty-white coat?”

Yes to all, and Ruby’s white fur coat would certainly be dirty by now.

“We tried to get her, but she’s too fast,” he said.

• • •

Thursday afternoon, another sighting near the cemetery led me back there. A week had gone by since the accident. Oak Hill’s gates were open. I stopped a groundskeeper and asked if he had seen Ruby.

“Sure, I have. We’ve all seen that dog, every morning this week. Down by the creek and up here along the fence line.”

Ruby was hiding out in Cruella territory. This could be a problem. I offered him and his men a bounty: Whoever caught her would receive a hundred bucks and a case of beer. He said he’d spread the word.

That afternoon I ran into Donna Shalala as she walked her dog, Cheka, in the park.

“Don’t you worry about the cemetery,” she said. “I’m not allowed to give you my key, but it won’t be a problem. Mrs. Graham called the caretaker yesterday and gave him an earful. If you need to get in, you just phone him and say so.”

I thanked her.

I only wish I could thank Mrs. Graham.

• • •

Ann Edwards, a volunteer from Friends of Homeless Animals who runs a bed-and-breakfast on Capitol Hill, became a fixture in the neighborhood that week. After serving her guests their morning coffee, she’d hop into her car and drive to Georgetown to offer us support and an extra pair of eyes.

Anne was my backbone. English-born and -bred, she was no quitter. When my spirits sagged, she insisted in her broad accent, “Never you mind. Ruby’s been spotted, that’s the thing. She’s a tough girl. And so are you. We shall find her.”

After so many sightings near the cemetery fence, we decided it was time for a more Zen approach. We would sit and wait. Call to Ruby in our minds. Expect her to appear again where she’d been seen before.

Officer Haisley, still calling us daily, advised, “Keep checking those traps. She’s got to be very hungry by now.”

The pet detective was more skeptical.

“Your dog’s not here,” he said. “I think she’s north. My dogs can’t find her scent. We need a solid sighting—you need to see her yourself—so we can pick up a real trail. I don’t trust the information we’re getting.”

I considered what the animal psychic had said—she’d insisted Ruby was up near Kalorama. Still, all these sightings of a white dog had come in near R Street.

Anne, Ben, and I decided we’d keep looking close to home. Thursday night we set up lawn chairs in Montrose Park, choosing a prime spot to see into the cemetery. The tombstones glistened white in the darkness. It grew cold. At 12:30, we packed it in and returned at 6:30 in the morning. We sat vigil all day Friday. Ruby did not show herself.

• • •

Saturday night, we received two phone calls. The first was from the cemetery caretaker’s wife, who kindly asked if we’d like to tour the grounds at dusk when Ruby might come out from hiding. Whether or not the gesture grew from Mrs. Graham’s influence, we were grateful. Ben and I geared up with dog treats and flashlights and walked the eerie paths for an hour. The night was still. We saw nothing, not even a ghost.

The second call came from a stranger just as we were going to bed. She had found a white dog on R Street hours before. I stopped breathing as she described the dog. It was all white, no brown spots. Short legs, blue collar, very small, only 15 pounds. It wasn’t ours. This news called into question every sighting we’d received. People had seen a white dog along the fence line, in the park and in the cemetery. But was it Ruby or this other pup? I wondered if Ruby was miles away—or dead.

I’m not Catholic, but I prayed to St. Francis of Assisi, the patron saint of animals.

• • •

Sunday morning, ten days into the search, a group of 15 volunteers from Friends of Homeless Animals was due to arrive at 7 AM for one last-ditch effort to find Ruby. At 6:30 the phone rang.

“Hello,” a man’s voice said. “I was walking beneath the Taft Bridge. I’m sure I saw your dog. I ran to a pay phone. It was only five minutes ago. Please come quickly. And park near Belmont.”

Ben threw on his clothes and hit the road. While I greeted the volunteers in Georgetown and planned our course of action for the day, Ben parked on Belmont—exactly where the psychic had told us to go the previous Monday. He slid down the hill we had tackled a week before. Ten seconds later, he found Ruby. She was breathing heavily in the tall grass. Ben whistled. She looked up, startled. Still too scared to come to him, she took off. Ben tumbled down toward the creek and pursued her.

Even running on three legs, Ruby was fast. She led Ben along the creek until Rock Creek Parkway loomed ahead. She tore across the road, narrowly missing the cars. Ben, frantic, dodged traffic and continued the chase.

Ruby stuck to the jogging paths, heading back toward our house and the cemetery. At one point, an older gentleman with two Labradors approached from the other direction. Ben yelled, “Stop that dog!”

The Lab’s owner crouched down like Johnny Bench, ready to catch her. Ruby stopped for a moment, sized up the situation, then chose the man as the easier target. She ran right through his legs.

• • •

The volunterr dog posse in Montrose Park was unaware of all the action until my neighbor ran up to us shouting, “Your husband’s down at the creek with Ruby! She just went into the cemetery—get in there now!”

Half of the dog posse ran back into the woods where my husband was tracking her. The others ran to the Q Street fence line to try to keep her from escaping. I rang Cruella’s doorbell, begging to be let into the cemetery. No answer. I leaned into the buzzer.

I heard a window bang open two stories above. An expletive flew out of it. Cruella was soaking wet.

“I am in the shower! I am not corning down there to let you in! Go away!”

“My dog is in the cemetery! Please, I’m begging you!”

“No!”

In a moment of synchronicity, Donna Shalala happened to be walking Cheka across the street right then. Cruella saw her as he slammed the window shut. Less than a minute later, the caretaker’s wife opened the gates. I ran to the creek.

Ben had not been so polite. He’d found a hole in the fence big enough for an animal and squeezed in. I met him at the creek’s banks. He fought his way into the brush, spotted Ruby, and forced her back toward the dog posse. They were waiting along the fence line where it ran into the creek.

When Ruby realized she was surrounded, she gave up and went straight to my husband’s arms, as if this had all been a game, and, shucks, it looked like she’d lost.

• • •

Friendship Hospital for Animals told us that another day or two and Ruby wouldn’t have made it. She was covered in ticks and had a broken leg, a 104-degree fever, and an infection. She hadn’t eaten much, if anything, in ten days. She was one tough girl.

After antibiotics, fluids, and food, she was deemed stable enough for surgery. A plate was screwed into her leg, giving her use of it again. After six days in intensive care, she came home. She’s made a full recovery.

As we waited to settle our $2,300 tab, a technician slipped us a card. It was addressed to Ruby and signed, “All of your friends at Montrose Park.” The technician took the bill out of our hands and told us it had been covered by dozens of donations.

Two days later, we invited everyone who had helped us find Ruby—half of Georgetown, the shelter volunteers, Donna Shalala, DC Animal Control, economists from the Fed, the pet detective- to celebrate with us in Montrose Park.

Ruby met her subjects—our new Washington friends—like a queen. The psychic sent her regrets. And Mrs. Graham? I hope she was watching from her front windows.

Cruella, to my surprise, sauntered up about an hour into the party. He bent down and patted Ruby’s head.

“Welcome home, girl,” he said sweetly. “Can I have some cake?”

This article appears in the September 2001 issue of Washingtonian.