Once, Ben Bradlee and his close friend, lawyer Edward Bennett Williams, planned to retire at age 50. They were, Bradlee recalls, going to be “sort of Lanny Budds,” traveling the world tackling big problems the way Upton Sinclair’s character did in a 1940s series of novels.

“We were going to solve the Boston school strike, whatever,” says Bradlee. “But you can’t get Williams to retire with a 105-millimeter howitzer.”

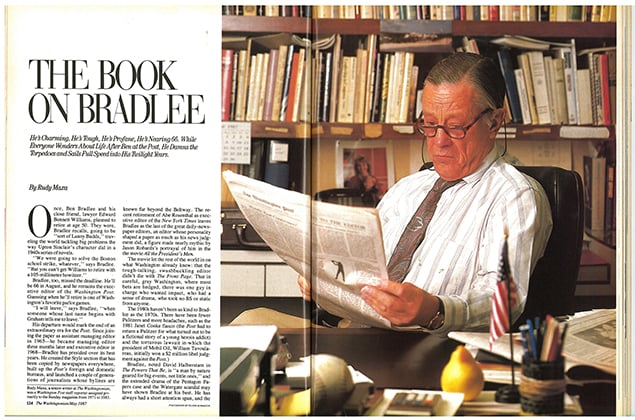

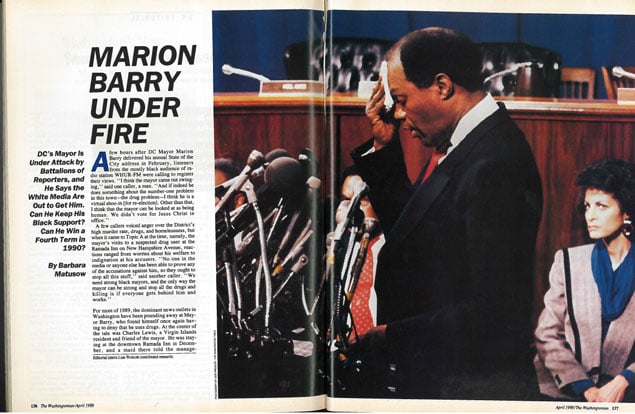

Bradlee, too, missed the deadline. He’ll be 66 in August, and he remains the executive editor of the Washington Post. Guessing when he’ll retire is one of Washington’s favorite parlor games.

“I will leave,” said Bradlee, “when someone whose last name begins with Graham tells me to leave.”

His departure would mark the end of an extraordinary era for the Post. Since joining the paper as assistant managing editor in 1965—he became managing editor three months later and executive editor in 1968—Bradlee has presided over its best years. He created the Style section that has been copied by newspapers everywhere, built up the Post’s foreign and domestic bureaus, and launched a couple of generations of journalists whose bylines are know far beyond the Beltway. The recent retirement of Abe Rosenthal as executive editor of the New York Times leaves Bradlee as the last of the great daily-newspaper editors, an editor whose personality shaped a paper as much as his news judgement did, a figure made nearly mythic by Jason Robard’s portrayal of him in the movie All the President’s Men.

The movie let the rest of the world in on what Washington already knew: that the tough-talking, swashbuckling editor didn’t die with The Front Page. That in careful, gray Washington, where most bets are hedged, there was one guy in charge who wanted impact, who had a sense of drama, who took no BS or static from anyone.

The 1980s haven’t been as kind to Bradlee as the 1970s. There have been fewer Pulitzers and more headaches, such as the 1981 Janet Cooke fiasco (the Post had to return a Pulitzer for what turned out to be a fictional story of a young heroin addict) and the torturous lawsuit in which the president of Mobil Oil, William Tavoulareas, initially won a $2 million libel judgment against the Post.)

Bradlee, noted David Halberstam in The Powers That Be, is “a man by nature geared for big events, not little ones,” and the extended drama of the Pentagon Papers case and the Watergate scandal may have shown Bradlee at his best. He has always had a short attention span, and the routine administration of the newsroom does not set his heart pounding. Some Post staffers say his presence has been felt less since Donald Graham became publisher and Leonard Downie became managing editor.

But no one at the Post is suggesting Bradlee retire. In fact, some fear he is the workaday reporter’s last champion, the only editor with the charisma, clout, and guts to override the corporate types who view the Post more as a profit center than a newspaper, more as a product than an adventure.

Bradlee’s fans think longevity is what becomes a legend most.

• • •

Benjamin Crowninshield Bradlee has always worked both sides of the street. Educated at St. Mark’s School and Harvard, fluent in French and social graces, he also curses like the sailor he once was. His charm is legendary—women of all ages find him sexy—but he can coolly freeze out those who displease him.

Jason Robards got him right in the movie. The actor growled like Bradlee and strutted like Bradlee. But while some of Bradlee’s junior editors try to emulate their boss—no American newsroom has seen as many men wearing shirts with bold stripes offset by white cuffs and collar—few can match Bradlee’s brash style.

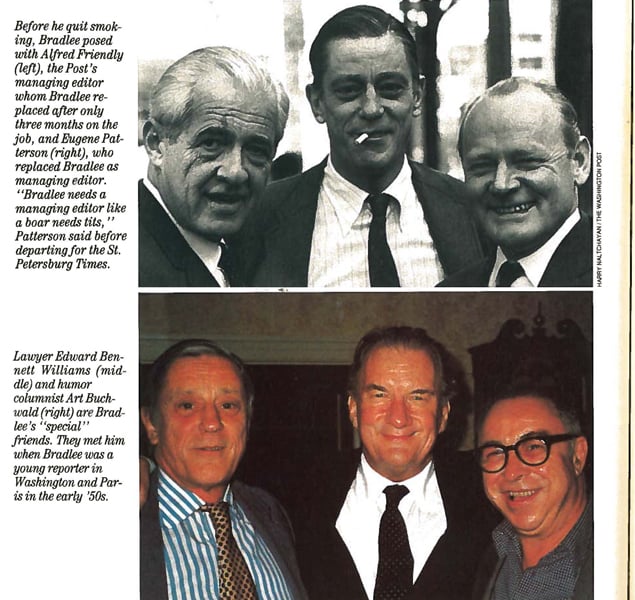

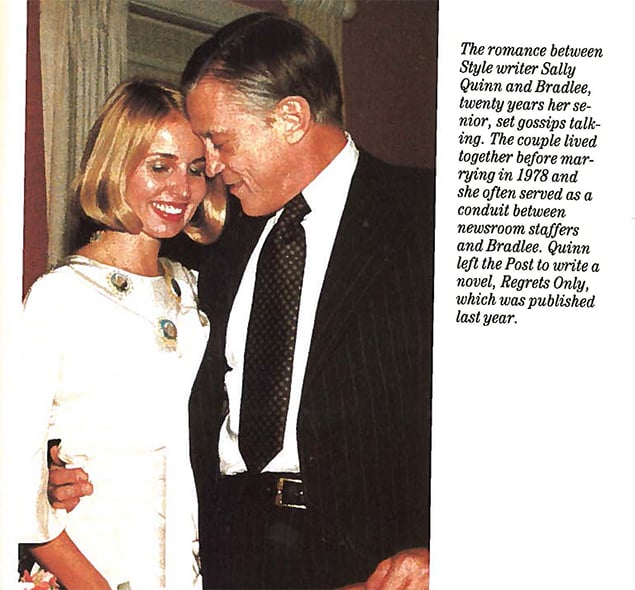

When he gave up his Kent cigarettes in 1975 after attending how-to-quitsmoking classes, younger editors lined up for the same classes. But no one wielded a swagger stick in the newsroom as Bradlee briefly did. And none can get away with what Bradlee can. A couple of Post editors’ careers nosedived when their marriages broke up and they began dating younger women; it is well known at the Post that board chairman Katharine Graham disapproves of such things. But Bradlee’s star remained bright after his 1973 separation from his second wife and in spite of his ensuing live-in relationship with Style writer Sally Quinn, twenty years his junior.

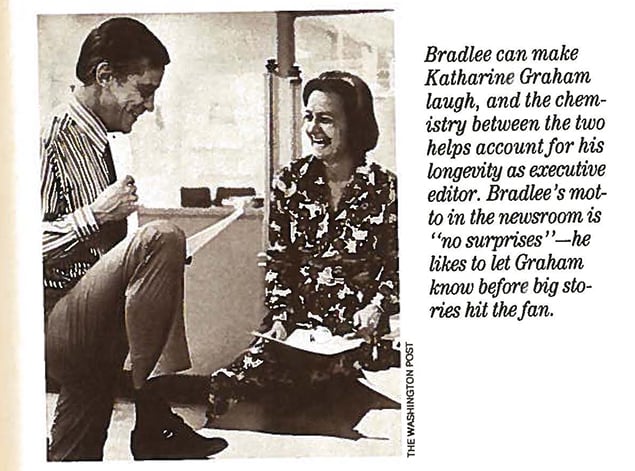

Bradlee has a straight-from-the-shoulder approach to life. “He’s basically an existentialist—yesterday doesn’t count because it’s gone; tomorrow doesn’t count because it hasn’t happened yet,” says his former managing editor, Howard Simons. And that appeals to Katharine Graham. She bet correctly that Bradlee’s verve would attract talent and move the Post into national prominence when she moved him from Newsweek to the Post 22 years ago. During those years, Bradlee’s detractors have waited in vain for him to fall from grace. He has maintained Mrs. Graham’s affections while fending off the ire and invective of every White House administration.

Lyndon Johnson loathed the Post’s turnaround on America’s involvement in the Vietnam war. (It was Phil Geyelin, a Katharine Graham hire on the editorial page, who reversed the paper’s hawkish course in 1969.) And LBJ despised Bradlee’s polished, Ivy League background as well as his past friendship with Jack Kennedy. The Nixon administration would have been happy to see the newspaper consumed by flames when it treated the Watergate break-in as more than a third-rate burglary. Jimmy Carter and his close aides had plenty of quarrels with the Post‘s reporting , and Ronald Reagan doesn’t often get a warm feeling reading his hometown’s dominant newspaper.

Katharine Graham usually stands above the fray—to the applause of her fifth-floor editorial staff—and Donald Graham is still an enigma as publisher. That leaves Bradlee as the lightning rod for most criticism.

“He’s the ultimate Teflon—nothing seems to touch him,” says one Post reporter admiringly. “Janet Cooke, the whole thing with the black community and the Post magazine …. “

When his newspaper makes a mistake, as in the Cooke affair and the inaugural issue of the new Sunday magazine, Bradlee pleads guilty and pushes on.

Bradlee’s reputation for swagger and brass can be partly attributed to his good looks: slicked-back hair, a leathery face etched with interesting lines, a quick, broad smile, and a barrel chest due to an exercise regimen that followed a childhood bout with polio. A Wall Street Journal reporter wrote seventeen years ago that Bradlee was “a gruff but witty and debonair man who looks rather like the Hollywood version of an international jewel thief.” Then there’s his trademark voice, all gravel and growl, that can purr, cajole, demand, or roar.

Bradlee’s reputation has been enhanced by an unusual vocabulary that owes something to his addiction to crossword puzzles, something to his French, and a lot to the lexicon of the locker room and military.

He has, for example, told his editors to look for the “holy shit” stories—articles that make readers pick up their morning paper and exclaim, “Holy shit!” When Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein protested that they—not the newspaper as a whole—should have received the Pulitzer Prize for Watergate reporting, Bradlee told them, “This paper had its cock on the chopping block.”

Former managing editor Simons remembers some of Bradlee’s Navy sayings, such as “‘making a stove from steel wool,’ meaning you can do amazing things with a little bit of information and work up from there.” During an editor’s meeting years ago, one participant mentioned vacationing in Ocean City.

“Ocean City?” Bradlee asked. “Isn’t that for enlisted men?”

A Post department head remembers Bradlee asking him about an upcoming event. The subordinate treated the question too casually, saying he had been wondering about the same thing. Bradlee turned stern.

“That,” he growled, “is why I’m asking you, lieutenant.”

And this is how Bradlee remembers the day the New York Times scooped the Post in 1971 by obtaining the classified Pentagon Papers: “The score was 36 to nothing, and we were trying to get even.” When a Style writer wrote a flattering profile of a movie star, Bradlee told her she’d written a “tank job,” a boxing term meaning to take a dive. Complimenting Ben Bagdikian on living behind bars for a series about prison life, Bradlee said, “I got to hand it to you, buddy. You’ve really got big ones.”

Off-color, streetwise talk is part of Bradlee’s modus operandi , and Post staffers consider such comments the highest of praise. Sarcasm and sparring are Bradlee’s ways of showing affection, a technique that some of his junior editors have adopted over the years—many of the Post’s most successful editors and reporters are professional wise guys.

Bradlee rarely spends much time chatting with wallflowers, the quieter staffers who lack a quick repartee.

“I’m very high on energy,” he says of his strategy for picking talent. “I don’t like people who are languid.”

Says a longtime staff reporter: “I think you could accuse him of favoritism and elitism and still be within your rights. But he is so damn charming; he has a way of making people feel good. But he also has a way of making you feel bad if you’re on his shit list.”

As a Post staffer, you know you’re in trouble if Bradlee ignores you, if he looks right by you as he strides through the newsroom and never pauses to make a smart-aleck remark about your work.

“He uses inattention as a management tool,” says William Greider, a former Post writer and editor who now writes for Rolling Stone magazine. “Some of it is not feigned. A lot of it is ‘Don’t tell me about the muck; tell me about the mountaintop.’ He could zing you in unpredictable ways and you’d say, ‘Holy shit, he is paying attention!’

“I went to the Post in ’68, and as a reporter for most of the next ten years, I probably didn’t have half a dozen conversations with Ben,” recalls Greider. “Yet somehow he conveyed to me that he liked what I was doing and that I should do more of it, take chances, swing from the heels, go for the bold, offbeat approach, dig beneath the surface—all the values an editor is supposed to communicate. He never said any of that in anything resembling a direct way, which I take as a kind of genius.”

Robert Barkin, once the Post’s assistant managing editor in charge of art direction, remembers being furious when publisher Donald Graham killed a redesign of the newspaper that Barkin had labored over for months.

“Ben said to me, ‘There’s a rule I live by: Don’t get mad; get even.’ And he does. It’s amazing—he never loses his cool; he always finds ways to turn things around to his own advantage.”

“Everyone thinks he’s got a tough shell, but he’s really a patsy,” says columnist Art Buchwald of Bradlee. “He never calls if everything is going okay. But if you’re in trouble, he’s always there.”

Bradlee’s two “special” friends, as he terms them, are Buchwald and lawyer Edward Bennett Williams. Williams and Bradlee met when Bradlee was a beat reporter at the Post in 1949 and Williams was trying cases in police court. Bradlee met Buchwald several years later when Bradlee moved to Paris, first to work as a press spokesman at the American Embassy and later as a Newsweek reporter.

For years now, the three men have met for lunch every month or so, most recently at Maison Blanche. They call their gathering “the Club,” and although they occasionally audition new members, the trio has an understanding that one of them will always veto adding another permanent member. Not even Katharine Graham—who, along with Buchwald and Williams, was a witness at Bradlee’s 1978 marriage to Sally Quinn-survived the veto.

Sometimes the interests of members of the Club don’t coincide. Williams remembers an incident that occurred years ago when he bought a piece of property in Potomac. He wanted to build a home on it but was told there was no city sewage and the land was not suitable for a septic tank.

“All I had was a very expensive place to play softball,” says Williams, who began a campaign to persuade the Washington Suburban Sanitary Commission to extend sewer and water lines to his new property. When the WSSC finally approved the extension, Williams walked out his front door the next morning “to see my picture on the front page of the Metro section and the Post saying it was costing the taxpayers $30,000 to give me sewer and water.”

But no damage was done. In fact, after the Post’s law firm wavered in the face of government opposition to the Post‘s printing of the Pentagon Papers, Williams’s law firm picked up the newspaper as a client, a relationship that continues today.

When Bradlee, Williams, and Buchwald have lunch, they draw matches to determine who pays the bill; the man with the shortest match loses.

“Bradlee is really dumb; he’s very weak on the match game,” confides Buchwald. “If you get back to Ben with that quote, you’ll get a ten-minute diatribe—he doesn’t like any publicity about his match game.”

Bradlee professes not to like publicity much at all and says that has been the biggest change in his life since the Post became an important paper.

“We are such public figures now,” he laments during breakfast—eggs over easy—at the Madison Hotel. “That never was true. I mean, I make a casual-ass remark to Sy Hersh—you know, that story that I haven’t had so much fun since Watergate …. “

What happened was that investigative reporter Hersh came to play tennis one Sunday at Ben and Sally’s Georgetown home. Bradlee says Hersh-another professional wise guy—”comes roaring on my court” with the Iran-contra scandal on his mind “and says, ‘Come on, Bradlee! You haven’t had so much fun since Watergate!’ And I say probably not, or something like that. The next thing, he’s giving a speech that is covered by the press at the women’s something-or-other, and in answer to a question, he says, ‘Well, I saw Ben Bradlee last weekend, and he says he hasn’t had so much fun since Watergate.”

It hit the fan. Here, said Bradlee’s considerable list of enemies, is the world-famous Watergate editor chortling over another national crisis.

“Ben Bradlee has become an embarrassment to the Washington Post,” wrote Bradlee’s nemesis, Reed Irvine of Accuracy in Media. “It is time he retired.”

Writing in Newsweek, the President’s recently retired communications director, Patrick Buchanan, said Bradlee had “exulted” in claiming that the scandal was more fun for him than Watergate.

To Bradlee, such saber-rattling was out of proportion to a “casual-ass remark” on his tennis court.

“To go from there to Pat Buchanan’s piece in Newsweek . . . that’s bullshit!” he snarls. “You know what a journalist means by fun-he doesn’t gloat. When we were thinking about statements to issue after we won our libel suit [in March an appeals court threw out the libel judgment against the Post in the Tavoulareas case], I said, ‘How about saying I haven’t had more fun since the Iran-contra scandal’? And everybody said, ‘Shut up, Bradlee!’

“You’re in a fishbowl. I like to say what I think, and I’ve got to watch that now.”

Bradlee arrives at the Post on 15th Street every weekday morning between 8:30 and 9. He drives to work from the Georgetown mansion he shares with his wife and their son, five-year-old Quinn, in his beige Subaru; the family’s second car is a four-wheel-drive Jeep. Bradlee reads the Post and the New York Times daily and looks at the Baltimore Sun and “the Moonie paper,” the Washington Times. He also glances at the Boston Globe, where one of his sons is a reporter. He attends both daily story conferences at the Post and meets with most prospective hires. He takes lunch around town—the Madison Hotel, Joe & Mo’s, Duke Zeibert’s, Mel Krupin’s—or sometimes plays tennis at midday. The only change in his schedule in the last ten years, says Bradlee, is that he no longer is on the rotation schedule with other senior editors to work weekends.

Sally Quinn is Bradlee’s third wife, and he is proud that he has remained friends with his first two. One of them, Antoinette (Tony) Pinchot, is single and living in Cleveland Park. When she married Bradlee, she was a beautiful blonde who was as quiet as Bradlee was outgoing. (Bradlee’s brother asked him why he was marrying Tony, and Bradlee replied, “I guess I just need a pretty blonde to tell me I’m marvelous around the clock.”) Bradlee attributes the breakup of that marriage to working day and night at the Post in the early ’70s.

His first wife, Jean Saltonstall, was from one of the first families of Massachusetts. They wed before he left to serve in the Navy in the summer of 1942. Today she is remarried and lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Their son, Ben Jr., is on a leave of absence from the Boston Globe to write a book about Oliver North.

Bradlee also has two children from his second marriage: After a short stay at Harvard Business School, Dominic (Dino) is a construction superintendent in the Catskills. Daughter Marina is married to a Loudoun County schoolteacher, Rick Murdock.

The story of how Bradlee met Sally Quinn has been distorted in the retelling. In 1969, Bradlee was looking for someone who would cover parties the way political reporters covered campaigns. He heard about a general’s daughter, Sally Quinn, who knew the city ‘s players, called her in for an interview, and liked her style.

Legend has it that when she told Bradlee she had never written anything, he quipped, “Well, nobody’s perfect,” and hired her. Actually, Philip Geyelin happened by Bradlee’s office just as Quinn was explaining how she had no experience. It was Geyelin who made the remark. But Bradlee did hire her on the spot, and she became the sassy writer in the Style section Bradlee had wanted.

Their romance in the mid-’70s caused great newsroom gossip. They attended functions together, and she moved into his townhouse just off Dupont Circle. Eventually, Sally redecorated both thetownhouse and Bradlee, whose wardrobe had once led someone meeting him to think he was a bookie instead of an editor.

“I would certainly like to take credit for that,” Quinn says today of Bradlee’ s preppie look. “Ben just never really cared for clothes …. He had pants that came up over his ankles. It’s impossible to get him to go shopping.”

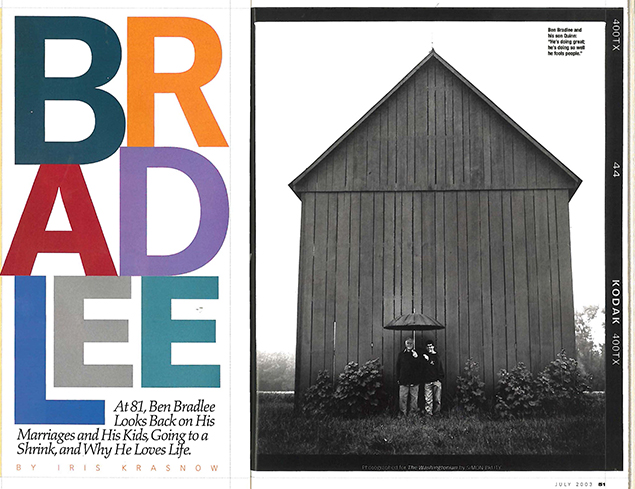

The Bradlees—who married in 1978—had a son, Quinn, in 1982. He was born with a small hole in his heart that required open-heart surgery when he was three years old. He is on medication and attends a special school, and doctors hope he will outgrow the side effects of the complication.

Bradlee and Sally Quinn socialize with several Post reporters and their spouses and play host to tennis-playing friends on their backyard court. For twenty years, Bradlee has owned a cabin in West Virginia, where he likes to spend weekends driving a tractor, splitting wood, and swimming. The couple spends each August on Long Island in a house, Gray Gardens, that they rent out the rest of the year. During August Bradlee socializes informally with the New York literary set—not many enlisted men there—and says he lives in jeans and polo shirts.

• • •

“Look at all these guys,” Bradlee said to a fellow Post editor years ago as they entered a meeting of the American Society of Newspaper Editors. “We wouldn’t hire any of them.”

“Don’ t worry,” replied his colleague. “They wouldn’t hire you, either.”

Bradlee doesn’t have the usual resume of a big-city newspaper editor. After Harvard, he served during World War II aboard Navy destoyers in the Pacific, then returned to New England to help start a newspaper in New Hampshire to rival William Loeb’s right-wing Manchester Union Leader. When Loeb bought his paper, Bradlee worked for about three years in Washington at the Post, then went to Paris to be press spokesman for the US ambassador.

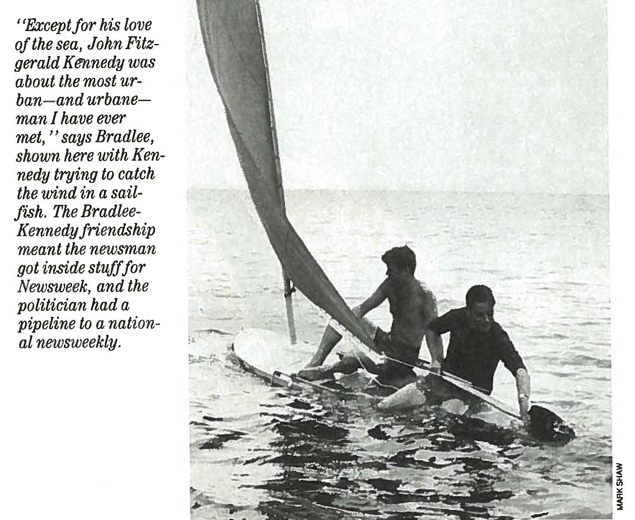

He joined Newsweek in Paris, and in 1957 moved to Washington as the magazine’s bureau chief. Two strokes of good fortune boosted his career: He became close friends with a young senator named John F. Kennedy, who bought a home next to his in Georgetown. And, while Washington bureau chief of Newsweek, Bradlee convinced the brilliant, mercurial owner of the Washington Post, Philip Graham, to buy the newsweekly.

Bradlee’s friendship with John Kennedy served him well at Newsweek (in 1975 he wrote a best-selling book called Conversations with Kennedy, based on the five years they knew each other).

Then in 1965, after the suicide of Phil Graham left her in charge of the Post, Katharine Graham hired Bradlee as managing editor of the Post. Some say his wit, charm, and take-charge personality reminded Graham of her late husband; whatever the chemistry, it worked, and Bradlee became executive editor in 1968 even as other yes-men who had served Katharine Graham as advisers fell by the wayside.

• • •

Bradlee is famous for standing behind his reporters. The Watergate scandal coverage, which was run mostly on a day-to-day basis by editors Barry Sussman, Harry Rosenfeld, and Howard Simons, is most often cited as an example of Bradlee’s willingness to take risks.

Al Hunt, bureau chief of the Wall Street Journal, remembers the 1980 Republican convention, when Lou Cannon of the Post reported that George Bush would be Ronald Reagan’s running mate. When a groundswell for Gerald Ford began to develop, Hunt recalls other Post editors coming up to Bradlee and saying, “Jesus Christ, what are we going to do?”

“We’re stickin’ with Louie,” Hunt recalls Bradlee saying.

Not that Bradlee’s news judgment is always perfect. On a Friday afternoon in July of 1973, the Senate Watergate Committee learned of the existence of Richard Nixon’s secret office taping system. Someone leaked the news to Bob Woodward, who called Bradlee at home at 9:30 on Saturday night. Bradlee listened in silence.

“I just wanted you to know, ” Woodward later recounted in the book he wrote with Carl Bernstein, All the President’s Men. “We’ll go to work on it if you want.”

“Well, I don’t know,” Woodward recalls Bradlee answering with slight irritation.

Woodward asked him how he would “rate” the story. Bradlee gave it a B plus. Woodward thought that wasn’t too much and apologized for calling his boss on a Saturday night. On Monday, the man who had installed it, Alexander Butterfield, told the world about the system that would eventually lead to Nixon’s resignation.

“Okay,” Bradlee said to Woodward the next morning, “it’s more than a B plus.”

• • •

One of Bradlee’s contributions to Washington journalism has been the phrase “creative tension.” That was his term for the internal jockeying among Post staffers for good stories and good display. At its best, creative tension was meant to sharpen competition on a newspaper staff that, following the folding of the Washington Star, had no real hometown competition. At its worst, creative tension has been divisive at a newspaper with many talented reporters but only so much space for stories.

“Joe Alsop once told me the ideal staff number was to get down as low as you possibly could and then cut 10 percent, and you’d then have a staff that, if they worked like hell, could almost get it all done,” says Bradlee. “For those of us who have been here a long time, it’s just a major change. We used to write six or seven major stories a day. Now there are some who write that many in a year.

“I gotta tell you, I listen to stories of other city rooms, and I’m absolutely convinced the Post is a Garden of Eden compared to them. You hear people laughing and whistling all day long.”

The Post has not been a Garden of Eden recently; most newsroom employees have been working without a Newspaper Guild contract for about ten months and without a raise in nearly two years. The troops are restless, and their general knows it—Bradlee has been through seven such wrestling matches and says the process “is glacial in its power and inability to change.”

Says Bradlee wearily: “I mean, it’s déjà vu. My God, I can tell you when the group of the best reporters will come in my office, and I can tell you practically what they’re going to say and when they’ll go up to see Don and what his reaction will be.

“My idea would be to bar bulletins—management as well as Guild—and get the most expensive suite in the world and put both sides in the room and say, ‘Come out when you’re through.’ With everybody paying for it, Guild and management. Graham would go crazy in a $1,000-a-day suite.”

Bradlee says he does not have a contract with the Post—never has-but a weekly paycheck is hardly the same concern to him that it might be to some of his staff. Back in the early 1970s, when top Post reporters earned about $20,000 a year, Bradlee’s annual salary was about $100,000. He also owned more than 1 percent of Post stock, which reporters calculated to be worth about $3 million several years ago, before the company’s common stock shot up to its current value of about $170 a share.

Writing in The Powers That Be, David Halberstam said that when someone suggested to Bradlee he might be rich, he protested that he had gone into debt to buy Post stock. He explained that as a finder’s fee for suggesting the purchase of Newsweek to Phil Graham, he had been given an option to buy Post stock at an attractive price; half of the money it took to buy the stock was borrowed, he said.

When he and Sally were about to pay $2.5 million in 1983 to buy their Georgetown home, Bradlee confided to a friend that he was nervous about the purchase because, he said, “it’s going to be the first time I have to touch principal.”

• • •

It is love of the game—not money—that keeps Bradlee at the helm of the Washington Post.

After he joined the paper in 1965, he would sometimes pass the office of Russell Wiggins, the Post’s executive editor and Bradlee’s boss. If he noticed the older man napping, Bradlee would discreetly pull the door closed. Bradlee has said lie doesn’t ever want to fall asleep on the job. And because one wall of his office is all glass and looks onto the newsroom, he’ll never be able to nap in private.

Today the Post is a different place. Bradlee’s angel, Katharine Graham, is still chairman of the board, but the era of Donald Graham has begun. While Bradlee plays fast and loose, Donald Graham plays it close to the vest.

“Institutions become big and prosperous and powerful,” notes William Greider. “On the up-curve, they can afford to have someone like Bradlee as the leader because he’s dynamic, innovative, aggressive, and willing to take chances. And then institutions grow mellow and fulfilled and they level off. I’m not suggesting a decline and failure—they kind of just go on.

“I think Ben continues to underestimate this town in terms of its cultural and intellectual depth,” says Greider. “I think the city in the last twenty years has become much more sophisticated and anxious for quality in every realm—arts and culture—in a way that the Post hasn’t quite recognized, and that’s partly Ben’s fault. Nevertheless, if you look at the Post today and then look at it twenty years ago, you would be staggered by the contrast. It was a rag. Bradlee put a lot of people in there doing things he probably wasn’t very much interested in, but he said, ‘Let’s go for quality.’ It’s a great game to sit around and talk about Bradlee’s weaknesses, but the headline is: Look at that newspaper.

“But can you do it forever?”

• • •

Today Bradlee says he feels terrific. He plays tennis well, though as a result of the polio he suffered as a teenager, he prefers to play doubles because he can’t run fast. Sally Quinn says he has a “murderous serve” and hates to lose, particularly to Sy Hersh. For his part, Hersh says, “The nicest thing about playing Ben is that he’s a man’s man on the court—he competes very hard, and he’s the most honest line caller. He puts me to shame.”

Bradlee says he has asked friends around the newsroom to let him know if he starts missing a step, if he should consider retirement.

“I have a lot of things I want to do after the Post,” he says. “I’d like to write some books, and I will.”

He has been offered “a lot of dough” to write an autobiography but says, “I can’t even contemplate that.”

Ben Bradlee has never been very good Bradlee says he has asked friends at looking back.

On Politics, Luck, and Sally

On the Washington Times: “I don’t understand how people ride over the problems of their ownership. Jesus Christ, I mean, what is that guy’s name, the publisher—Bo Hi Pak? He ran the South Korean CIA here, his name shows up in the Oliver North documents. What other foreign government might he be working for? Certainly, if he was a representative of an Iron Curtain country it wouldn’t be tolerated. I think they do some things very well. I think it’s a good-looking paper—their make-up and layout.”

On how marrying Sally Quinn changed his life: “I got a lot of younger friends; she’s almost twenty years younger than I am. That certainly has been invigorating for me, great fun. And then, of course, the child [Quinn, their son] has been a powerful influence on my life, notwithstanding the other three children I had.”

On his life: “I’ve been wonderfully lucky. My whole association with the Kennedys was fortuitous, accidental! mean, Jack bought a house next to us. The role I played in getting the Washington Post to buy Newsweek was essentially fortuitous. Phil Graham’s mood, for him to buy it nineteen days after the first conversation held with me—stunning. And my whole relationship with Katharine [Graham] came along at a time in her life when she had decided to do something important with the Post.”

On the low points: “You don’t think Tavoulareas was a low point—a $2 million libel suit you lost for seven and a half years? People don’t realize that the day the verdict against us in the Tavoulareas case was returned was the day Quinn was operated on for open-heart surgery. That was the longest f—ing day in my life.”

On politicians: “Obviously, some of them take themselves hopelessly seriously—they are nowhere near as important as they think. One of the things about journalism is that you tend to outlast the politicians. As a profession, you outlast them all. I have a fundamental respect for people who go out and force the public to judge them the way a politician does. I think journalists do that every day. You sign a piece or put your name on a masthead, it says: ‘This is the best I can do.'”

On his politics: “Despite what the Patrick Buchanans of the world might say, I’m very unpolitical. I’m the bane of the liberal community because I’m not on committees to free this or that. I never demonstrated in the ’60s or ’70s. I don’t think that way.”

On his relationship with Abe Rosenthal: “He liked to beat my ass, and I liked to beat his. I once tried to get him to do something he wouldn’t: I had this theory that we could vanish background briefings and off-the-record stuff if we pooled our resources … to get up [and walk out] if they said something was off the record. But you can’t get the Post and the Times to agree on anything.”

On why he turned down a Gridiron Club membership: “I thought it was at worst a group of people in bed with their sources, and I thought that had a potential for corrupting the process. I don’t belong to anything.”

On how managing editor Leonard Downie’s statement to the Wall Street Journal that he was heir to Bradlee’s job played at the Post: “Not great. I think he was embarrassed by that. But you know, it’s going to be decided by Don [Graham], and it’s going to be decided when it’s decided.”

On the Post after Bradlee: “The thing that Post watchers have to understand is that it’s going to be different. It’s just a waste of time to think about it. You know, people really want it both ways. They say the trouble with the Post is that we shoot from the hip. And then they say if Bradlee leaves, it’ll be boring.”

Rudy Maxa was a Washington Post staff reporter assigned primarily to the Sunday magazine from 1971 to 1983.

This article originally appeared in the May 1987 issue of Washingtonian.