One of the highlights of teaching college journalism is bringing students to the Washington Post to hear from Ben Bradlee, the newspaper’s longtime executive editor, who in 1991 became vice-president-at-large.

As he speaks about his colorful past, the students are as hushed as I ever see them, enchanted by the arrestingly handsome veteran of the news business who is larger than life in his presence and experiences. He documents this in his memoir, A Good Life, which tells of his six-month bout with polio at age 14, graduation from Harvard, his 3 1/2 years of naval service on a destroyer in the south Pacific during World War II, a close relationship with President John F. Kennedy, three marriages that produced four children, and leading the Post through its unraveling of Watergate, the biggest political scandal in American history.

The fit and energetic Bradlee still goes to the office almost daily, yet his priority is no longer the mad scramble for news. His primary focus is his family—his wife, writer Sally Quinn, and their son, Quinn, a charismatic college sophomore who has weathered physical and learning challenges and is now thriving. Here is how Bradlee describes Quinn in A Good Life, a child who had 5 1/2-hour open-heart surgery by the time he was three months old:

His body had been unseamed, then closed with more than eighty stitches, and penetrated by more tubes and wires than I could count. He was fighting for his every breath, eyes tight shut….

How does an infant learn to fight that hard? Through tribulations that defied understanding—seizure disorders, speech difficulties, and learning disabilities—a valiant young man has emerged.

The last time my class visited Bradlee, he told us: “There comes a point in a person’s life when you look back and wonder if your life made any sense.” Struck by that, I asked if I could come back alone and talk to him about his climb down from executive editor of the Post to a man content these days just to have the title of Dad and to tool around his 200 acres on the St. Mary’s River in southern Maryland.

Here is Ben Bradlee at 81, the raspy-voiced legend who epitomizes resilience, optimism, and passion, the three qualities researchers believe to be the secrets to aging well.

• • •

At my age, you do question your life, and you do admit to any kind of failure. I’m not totally proud of everything. I mean, I wasn’t very good at the marriage business. It took me a while to get the hang of that. But I don’t believe for a life to make sense that you have to be all about success.

I’ve been in the newspaper business for a long time, and journalism has always been very important in my life. In looking back, I see that it was always a goal to be involved in something I felt passionate about, and this was it. I have never doubted whether I was in the right business. I love this business. In many ways, I was married to the newspaper, and that didn’t help my first two marriages. Breaking news excites me on every level, from messes in the White House to John Bobbitt getting his tallywhacker whacked off by his wife.

Working at a newspaper—this is my real self. Even now, my relationship with the Washington Post is umbilical. I still come here almost every day. And I don’t have to look for things to do. I make speeches; I’m a sounding board for editors and reporters. I’m very engaged with this place. I stay connected because it feels right; it has always felt right. And it is a marriage in the sense that it’s a deep, personal, satisfying bond.

The pinnacle, of course, was Watergate, and that’s vaguely discouraging to think that you peaked 30 years ago. But historically, there was never a news story that really had this impact—until September 11. Everyone around the world knew about Watergate and Woodward and Bernstein; they knew about me. But I don’t miss that. No, I don’t miss that at all. Because I never felt like that person. I never woke up and looked at myself in the mirror and said, “You powerful son of a bitch, you can do anything.”

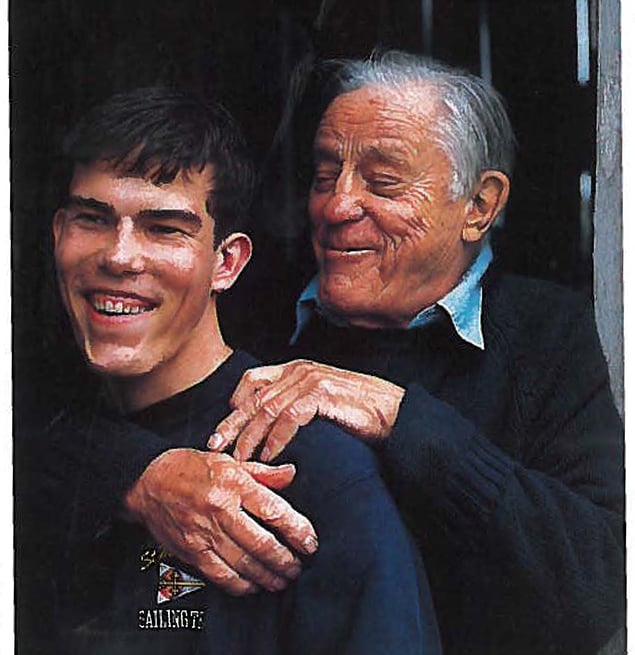

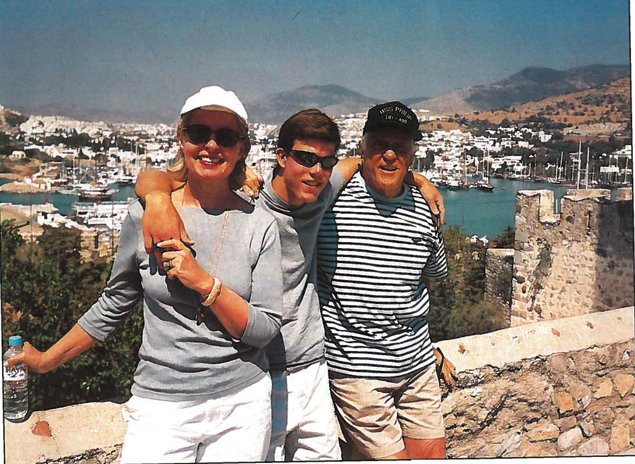

What has dominated my life for the last 20 years, and really forms who I am, is my son Quinn. He graduated from high school with honors, and that was unbelievable. I was in heaven. He dominates both Sally’s and my life because we wiii always need to nurture him and to protect him and to give him the confidence that those children lack. But he’s doing great, he’s doing so well he fools people; you don’t pick up right away on his disabilities, provided you don’t talk quantum mechanics with him. He’s good-looking and he loves people. I’m so proud of that kid.

Really, Quinn changed my life. In my other marriages, I cheated my kids. I wasn’t around while they were growing up. At one point, when Ben was young, I wasn’t even in the same country for a year. He is now deputy managing editor of the Boston Globe (on leave to write a book about Ted Williams). It’s just fantastic for him and for me.

But by the time Quinn came along in 1982, although I was still editor of the Post, it wasn’t that frenetic scramble as it was during Watergate and other eras. I never felt like I had the job done, but I felt that I was on top of the job. I had more time on my hands. So Quinn was really the only child of mine I saw a lot of growing up. I mean, Jesus, from the moment he was born and holding his tiny little hand in the oxygen tent to giving him hugs every morning before I left for work, I have been very involved with this boy. I had to be; he was in such need of us. He will always be in need of us.

I’m glad to where I am right now. I don’t have a ten-year plan. When opportunities come up that excite me, I do them, especially if it is something challenging. A few months ago I went to the Mideast and sat on a panel that spoke to 800 Arab journalists on American attitudes toward the Arab world. That was a lot of fun to do. And I’ll go on Larry King or other shows when an important story comes up and they want my view. But when things come up on weekends, I often won’t do them because I’d rather be with the family.

Being 81 feels bad in the knees, but it doesn’t feel bad anywhere else. When on the land, I’m out in the woods five hours a day with my toys, my tractor and chain saws. I love to find a little parcel that is overgrown with vines next to a swamp and clear it and plant it with something beautiful. Yeah, I really like this outdoor life, the guy thing. And I stay out there l until I am physically exhausted. In the past, I didn’t have the time to do that. I worked most Saturdays and Sundays.

I love this life right now, I really do. And the love of my life is to be in the country with Quinn, which we’ve done since he was a child and he’d go out there with a tiny hatchet and we’d work together. His attention span was about 20 minutes; then he’d wander off and discover something else in nature. I used to go out in the woods with my own dad, but I am a much different father with Quinn than he was with me. I mean, I wear my heart much closer to the sleeve. My father told me that he loved me once in his life, and he must have been 65.

I remember exactly what I said back to him. I said: “I know that, Dad. I’ve known that all my life, and you don’t have to say that. But I’m glad you did.” And I was glad that he did; it meant a lot. I probably tell Quinn every day of his life that I love him. I hug him and kiss him all the time, three or four times a day. I never kissed my father much that I can remember.

I’ve had no problem during my life going to shrinks if necessary. When you have a busy life it’s good to stop for introspection and reflection. And I have always been reflective about relationships, especially if relationships go sour. All the shrinking I’ve done taught me that you have to talk your way out of the rough patches into an understanding of what caused them.

This marriage works. Not only do we share this common preoccupation with Quinn, but Sally’s in the news business. She loves what I love. That’s been a great treat to have shop talk as pillow talk. Also for me, marrying somebody that much younger—Sally’s 20 years younger—was marvelously invigorating. Suddenly I developed this new circle of friends in my fifties who were in their thirties. Even now, I have only a handful of friends older than me.

I’d like to think, even at 81, that I’m continuously growing, yet I like that things have slowed some. I don’t have to be listening to the television and suddenly hear something that makes me fly out of the house and go down to the newspaper at 10 PM and start on a story. I know who I am. Let’s put it this way: I know enough about who I am, and maybe I don’t want to know any more than this. Perhaps I have a sign somewhere still inside of me that says: “Don’t go there.” But I don’t think so. I’m really quite open in a way that surprises people. I don’t feel I have a hell of a lot to hide.

Obviously I think about dying, but I don’t spend much time thinking about getting older because there’s always some damn thing on my calendar that I have to do. The Quinn hurdles go on and on, and they will for the rest of his life and for the rest of my life. I can’t think of anything I really desperately wanted to do that I haven’t done. I wanted to write a book. I wanted to help the Washington Post be a great newspaper. I wanted very much to help Quinn shine. I’ve got all the damn houses I need. I’ve got a lot of good friends. I’ve seen the world. What else could I want?

To be happy in your life depends on how you adapt to the situation in front of you when problems arise. Do you adapt with resilience? Do you adapt with hope? And I’ve always had that. I’m hopelessly the glass-is-half-full kind of guy. Even with all the craziness in the world today, I don’t worry much about being blasted into kingdom come. What can I do about it? I’m only interested in restricting my efforts and restricting my worries to things that I can do something about.

Journalism is dedicated to finding the truth, and I guess in philosophical terms, I know my truth, what makes me the happiest. And that is to be in the company of people I love.

I’m not as overtly productive as I once was, but I feel good. I’ve got a fake knee; one is metal. But it’s the only health thing I’ve got. I’m in good shape. No, I wouldn’t change much about this life. I would say the one constant for me has always been that I never stayed doing something that I really felt cornered by. I’m in a good marriage now, but in the last analysis, it is really your life, and you’ve got to find a way to make it work. And when it doesn’t work, you need to fix it and get back on your feet.

Iris Krasnow is a best-selling Annapolis author and a journalism professor at American University. This article is excerpted from her book, “Surrendering to Yourself,” from Miramax Books.

This article originally appeared in the July 2003 issue of Washingtonian.