Relative to the length of his presidency, no commander-in-chief may have a deeper visual archive than Gerald Ford. That’s the guess of Michael Martinez, a photojournalism professor at the University of Tennessee who’s studying six decades of official presidential photography, and has already spent a great deal of time sifting through the work of David Hume Kennerly, who spent two-and-a-half years capturing nearly every minute of Ford’s brief stint in office.

“It’s to build a narrative,” Martinez tells Washingtonian of official White House photographers’ work. Having a full-time photographer only goes as far back as John F. Kennedy, who created the position when he brought in Cecil Stoughton to develop the “Camelot” narrative. Before Kennedy, most official presidential photos were taken by a string of random military photographers, Martinez says. But not all presidential visual legacies are as story-driven as Kennedy’s, or as volumnious as Ford’s and Barack Obama’s, both of whom are photographed as much with their families as they are on official White House business.

“Sometimes they get a feel for the family, and sometimes we get the coldness of the office,” Martinez says. “Nixon was very controlling, and Ollie Atkins didn’t have unlimited access, he was more of a public relations guy.”

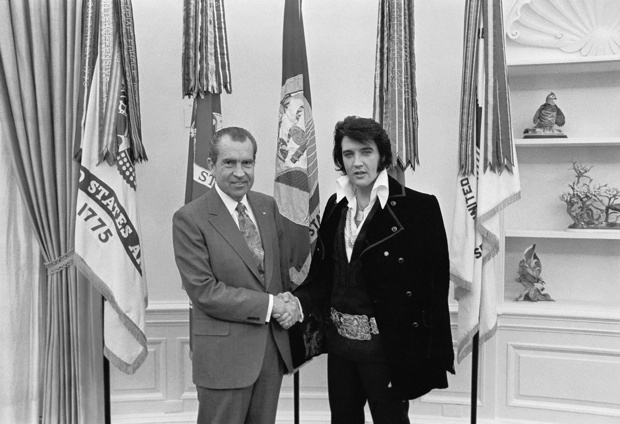

Atkins had had a long career in newspaper photograph before signing up with Nixon in 1968, including several World War II campaigns in Africa and Europe. But in the White House, he mostly captured the ceremonial moments for an otherwise media-sensitive president. That’s why one of the most famous images from Nixon’s presidency—a grip-and-grin shot with Elvis Presley—feels so static.

“You could subsitute a head of state, a governor for Elvis,” Martinez says. “The only reason it’s so desirable is because it’s Elvis.”

Kennerly, on the other hand, wound up being one of Ford’s closest confidants. While Kennerly’s most memorable photo might be the one of Ford reaching down to pet his golden retriever, Liberty, the former Time photographer had practically unfettered access to the Ford family’s most private moments. Martinez is particularly fond of one of President Ford visiting his wife, Betty, just after her breast-cancer surgery at Bethesda Naval Hospital, and another of Susan Ford preparing to sub in on ceremonial duties during her mother’s recovery.

Not all presidents have been as available as Ford, and some have been even more restrictive than Nixon. Jimmy Carter eschewed having an official photographer entirely, while Bill Clinton—who had Bob McNeely—also left behind a fairly conservative photo archive. Ronald Reagan and both George Bushes were more open with their photographers, as is Obama with Pete Souza. Martinez’s research also tracks changes in photography as a profession and a medium: Reagan’s first-term photogapher, Michael Evans, made the switch to full-time color portraits, while George W. Bush’s shooter, Eric Draper, jumped from film to digital.

One of the biggest factors determining what kind of visual legacy the public gets is whether a president gets the right photgrapher, Martinez says. These relationships can start years before a president actually enters office, and often last long after a term is complete.

“Defining the right photographer is pretty difficult,” Martinez says. “Because they campaign for two-plus years before the election, you have your pick of some good ones. I think the question is more so whether they would want to grant any sort of great access, whether they’re comfortable with the photographer and comfortable with their own skin to let people around them. When you’re president you’re never alone.”

Souza, the current occupant of the job, had his first White House stint during Reagan’s second term, but he’ll be remembered more for his work with Obama. Souza first took photos of Obama on assignment for the New York Times in 2004, and latched onto the then-senator’s presidential campaign staff in early 2007. But Souza’s bigger legacy will be as the first White House photographer whose work is transmitted to the public almost in real time, thanks to his big followings on Twitter, Instagram, and Flickr.

“He’s doing a photo stream and direct to the public,” Martinez says. “The media can pick it up, but the public can just sit there and watch it. In previous administrations, they had to go through traditional media of some sort.”

But there’s a flip side to that progress. While Martinez credits Obama as one of the more generous presidents—”You see the interaction of Michelle and Barack and the kids,” he says—Souza is also doing as much PR work as he is archival work, something that started on the first day of the Obama Administration.

“When Chief Justice Roberts screwed up the swearing in on Inauguration Day, there was a re-do private ceremony,” Martinez says. “Media were not allowed in. It was a handout from the White House Press Office.”

It’s a tactic the White House has kept up as it has kept news photographers out of the room during many official presidential moments, much to the frustration of the current crop of photojournalists assigned to cover the president. “A government photographer is no substitute for an independent, experienced photojournalist,” the White House News Photographers Association said last February when the administration refused to open the Dalai Lama’s visit with Obama to news cameras, but later distributed a Souza photo for media use.

That’s a bad trend for journalism, but it also damages the reputation of Souza and his fellow White House photographers through the years.

“Every once in a while that thing happens, and that’s not good, because it becomes a PR function, not a documentary function,” Martinez says.

Find Benjamin Freed on Twitter at @brfreed.