Come December, Charles Randolph-Wright will have two plays showing in Washington at the same time. An adaptation of Akeelah and the Bee, which debuted in Minneapolis, will open at the Arena Stage on November 13. On December 1, Broadway hit Motown the Musical will arrive at the National Theatre. “It’s thrilling,” Randolph-Wright says. “DC is like a second home.”

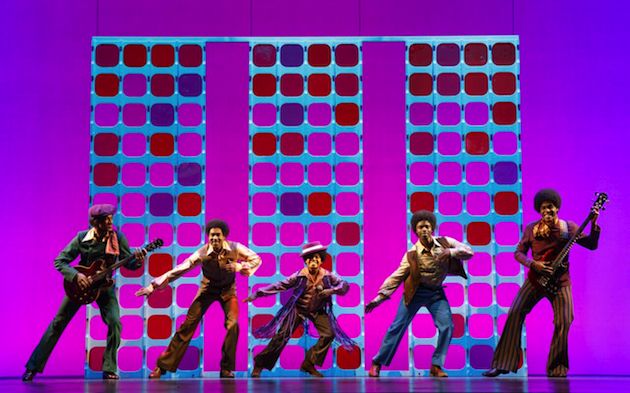

The two shows have more than a director in common. Akeelah is based on the 2006 film about a girl from a public housing project whose brains and resilience lead her to the Scripps National Spelling Bee. Motown is adapted from Berry Gordy’s book about his iconic record label, which helped launch the careers of artists like Diana Ross and Smokey Robinson. Randolph-Wright was drawn to these plays because they both send their characters on a boundary-crossing, hurdle-jumping journey to achieve their goals.

“Geography doesn’t limit your dream. Your neighborhood doesn’t limit your dream,” he says. “No matter where you are from, no matter who you are, color, etc. You can go after your dream. That’s what Berry Gordy did. That’s what Akeelah did.”

This message shows up often in Randolph-Wright’s work and is even reflected in his own life. He grew up in York, South Carolina and graduated from Duke University with a double major in theater and religion. He studied Shakespeare in London and dance in New York City, eventually getting an ensemble role in the original cast of Dreamgirls on Broadway. He has since built a prolific career directing and producing for theater, film, and television, where his credits including episodes of the ABC Family series Lincoln Heights and the Showtime series Linc’s. He’s a resident playwright at Arena Stage; in 2010, he directed Duke Ellington’s Sophisticated Ladies, which broke Arena’s box office record.

Though his resume covers a lot of ground, Randolph-Wright chooses his projects carefully. “There are a lot of things I turn down,” he says. “I don’t ever want to settle for some piece that’s not expressing the things that are on my mind. I do feel a responsibility as an artist to do the kind of work that I do.”

Part of that responsibility involves conveying to young people, especially young people of color, that they shouldn’t limit their ambitions. “I realize the importance of kids seeing people who look like them,” he says. “When they see that, they then have permission. They are enabled to go after something, to believe they can attain a certain dream.”

When Randolph-Wright goes to the theater, he’s often one of only a few people of color there. That imbalance is echoed in the stories told onstage. “Too often the people making the choices of shows pick the shows that relate to them,” he says. “And the people who are doing that don’t look like us.”

In recent years, television has made progress in diversifying its stories and casts, but Randolph-Wright says live theater, particularly on Broadway, hasn’t followed suit: “I believe that television is winning that game. We must do better in the theater, we must.” In that realm, however, Washington is performing better than New York. “The audience is a true mixture of people,” he says of DC theater. “You have every type of person. Every age, every color. That’s unique, unfortunately, in the world of theater.”

The title character of Akeelah and the Bee is African-American, and the cast features Latino, white, and Asian children. Motown the Musical celebrates the legacy of some of music’s most influential black artists. Randolph-Wright hopes that bringing these stories to DC stages will have a unifying effect. “It’s the nation’s capital,” he says. “We’re so divided in our country. I hope that politicians come and let go of their colors, their red and blue colors, for an instant. That’s what we have to focus on. What can we do together, as opposed to what do we do to keep us apart.”