Parents of preschoolers expect to hear about the typical misdeeds when they get that first call from a concerned teacher.

Your child doesn’t listen. Your child has a biting problem. Your child calls everyone “stupidhead.” When Jenny Rogers was pulled aside by her son’s pre-K teacher in Rockville, the issue was different: Her son, William, couldn’t write.

He could hold a pencil, but not correctly. His letters were barely distinguishable, and he couldn’t write his name. Straight lines and simple shapes were impossible. The teacher urged Rogers to get four-year-old William some extra help. (At the family’s request, I’ve changed their names.)

Rogers hired a handwriting tutor, and after that yielded almost no improvement, she took the teacher’s advice and sought an evaluation from an occupational therapist. The assessment found—no surprise—that William had poor fine-motor skills. What was surprising, however, was the recommendation: “a global occupational therapy (OT) approach.” Because William’s issues sounded severe, the family enrolled him in therapy sessions after school.

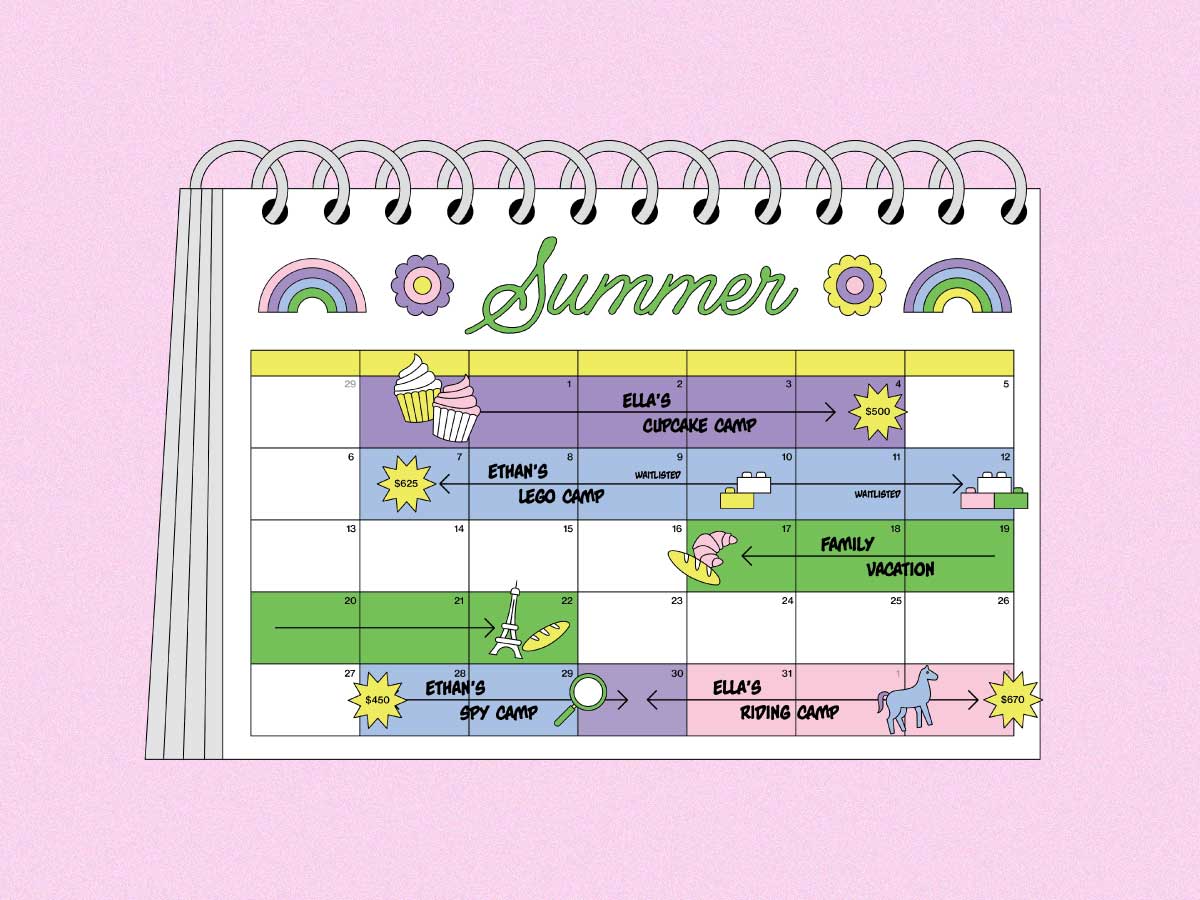

Each week, the boy would knead putty and practice using pincers to hone his fine-motor skills. He also did all kinds of exercises that seemed to have nothing to do with writing, such as tossing balls (for hand/eye coordination) and jumping on trampolines (to develop gross-motor skills). All told, the treatment cost the family two hours a week for the entirety of his first-grade year, not to mention thousands of dollars.

Four years later, William is pretty accomplished at gymnastics, an interest he discovered thanks to OT. But he still has “terrible” handwriting, his mother says. “I bought into the idea of ‘you don’t want your kid to feel bad about their issues,’ so I was happy to help if I thought it was going to help,” she explains. “Whether it helped in the end? I don’t know. Am I sorry I did it? I don’t know.”

Rogers’s story will resonate for any Washington parent who has received the out-of-the-blue phone call or found the note in the backpack from a worried teacher. Suddenly, your child’s idiosyncrasies—she’s clumsy, she won’t walk barefoot, her pencil grip isn’t perfect—keep you up at night. What if something bigger is wrong? you think. If I don’t do something now, will it get worse? Before you know it, you’ve lost perspective and become convinced your sweet preschooler will be in trouble if you don’t get her help right now.

Today, schools and specialists are steering kids toward a surprising place: OT, a therapy once reserved for the injured and the mentally disabled. And parents, understandably eager to support their children, are going along with the treatment as recommended, at price tags of $3,000 or more a year.

Occupational therapy, at its most basic, involves a host of customized strategies, activities, and training that help people navigate daily life without difficulty.

An adult who’s had a stroke might receive OT to relearn how to feed herself. The elderly could go see an OT (as a practitioner is known) in search of strategies for safely using the stairs.

As a profession, OT goes back a century, to the post–World War I era when therapists helped mental-health patients and veterans with daily life. Soldiers in traction, for example, received OT to learn basket-weaving or sewing or some other “purposeful activity” that might help stave off depression. But today, only 2 percent of the certified OT practitioners in the US focus primarily on mental health. Almost a third go into pediatrics—more than any other specialty.

The interest in kids became more pronounced in the 1970s when A. Jean Ayres, a psychologist and OT, published Sensory Integration and the Child, which posited that our senses are integrated by our central nervous system. According to Ayres’s theories, a typical person when faced with a noisy environment, for example, will intuitively watch someone’s lips to better understand what’s being said—the sense of sight enhances sound. But if your senses can’t properly work together, you can’t hear as well, which for a young child can mean social isolation and academic hurdles. Ayres’s research led to OT strategies to help kids overcome these kinds of problems. In 1975, the Education for All Handicapped Children Act—meant to ensure that disabled youth were enrolled in school and offered individual help—placed countless OTs in public schools.

Occupational therapy’s move well beyond its origins—to treating otherwise mainstream children—is a more recent phenomenon. Today’s teachers may suggest OT because your child needs to learn his body’s boundaries better—he bumps into things or invades others’ personal space. Or he may be fidgety or have “too much energy.” An OT will say that therapy might help him cope with life better, resulting in more confidence and overall success.

These suggestions are happening at early ages. In Washington, the National Child Research Center, Gan HaYeled Preschool, St. Columba’s Nursery School, CCPC Weekday Nursery School, Clara Barton Center for Children, Temple Sinai Nursery School, CCBC Children’s Center, and Wonders Child Care are just a few children’s programs that either have an OT on staff or contract with an OT consultant. A local firm co-owned by OT Judi Greenberg has contracts with 30 area preschools.

But whether OT works for these kinds of kids is open to debate—and a critic might be wary of some conditions under which consultants prescribe the therapy. Occupational therapists give teachers good concrete tips—they might tell them, for instance, to have kids do wall push-ups before writing activities to maximize focus. But in some classrooms, the consultants screen every three- and four-year-old. And if they don’t find “issues,” schools might arguably question the need for their services. While the purported intent is admirable—to detect problems early before they worsen over time—it’s possible that many of these issues will resolve on their own.

“OTs will be like anyone else,” says Allen Frances, a psychiatrist who writes about the “medicalization of ordinary life” in his book Saving Normal. “If you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail.”

Local OTs such as Heather Jackson-Peña, owner of Young & Well in Rockville, have seen a real shift in their practices. “Much of the intervention we’re providing in pediatric OT is not necessarily for children who have significant or even mild disabilities,” she says. “In some cases, they are only delayed by about six months, or they may be nine months younger than everybody in their class.”

How did we get here?

It’s partly a question for a sociologist. Today’s full day of kindergarten is more intensive than the half day of yore, and the expectations for kids when they arrive are higher than they used to be—there’s less free play and more academics. Preschools feel the pressure. “I think the teachers do feel that underlies everything—that they need to get these kids ready [for kindergarten],” says Emma Stewart, director of CCBC Children’s Center in Chevy Chase DC.

Especially boys, whose fine-motor skills lag behind those of girls, says Michael Thompson, a child psychologist who cowrote Raising Cain: Protecting the Emotional Life of Boys. Not surprisingly, boys make up a majority of local OT referrals—Jackson-Peña estimates that as much as 85 percent of her Rockville practice is male.

In the past, Thompson says, “kids could spend hours a week playing games, building forts, weaving sticks together—you know, just playing in a way that helped them develop their coordination.” Today, he says, “we’ve replaced that with OTs, and they’re personal trainers for kids.”

Does your child need help getting dressed? Hate having his hair brushed? Tire easily? Does she have strong aversions to particular foods, slump down when coloring, or often need to have instructions repeated? Could your kid jump on a trampoline all day? Do bright lights upset him, loud noises? Is your child extremely ticklish?

That’s a small sampling of typical OT screening questions.

Does it sound as if your child could qualify? Probably. But does she need therapy? That’s a different question.

“There is a fine line between benefiting [from] and really needing OT,” says Kristen Masci, an occupational therapist and the owner of Skills on the Hill in Arlington and Capitol Hill. “We have to be really careful . . . when we do evaluations to look at the big picture.”

Many parents nonetheless leave an OT consultation feeling it’s necessary. Private evaluations, which take hours, generally cost $500 to $1,250, and the reports are riddled with quasi-medical, highly technical language, with terms like “vestibular system” (related to your sense of balance), “low tone” (floppy muscles, roughly), and “tactile defensiveness” (oversensitivity to touch). There’s much discussion of your child’s brain. “It freaked me out,” as one mother summed up the process. And in an area with so many resources, it’s easy to get swept up in the sales pitch.

I talked to a Capitol Hill mom who can’t seem to shake the worry that something might be wrong with her three-year-old—despite getting her daughter’s hearing tested and having her evaluated for OT through government services, both of which reported nothing irregular. When a private evaluation found her daughter to be “average to below average” in some areas, the mother enrolled her in weekly sessions, at $135 an hour. “She’s slightly behind,” she says. “If you have something in your gut that’s worrying you, it’s better to be proactive.”

Plus, she says, her daughter’s OT “just seems like play and interaction, and I feel like my daughter is getting the positive benefits without worrying she’s getting a therapy session.”

Kids do seem to have a blast at OT. The workspaces resemble very technical toddler gymnasiums, with myriad swings, slides, hoops, maybe a climbing wall, and plentiful chains dangling from the ceiling. At Leaps and Bounds in Tenleytown, Allison Mistrett walked me through how she has children swing on a tire while rearranging small figurines—picking them up from one spot while swinging, then dropping them in another. For a lot of kids, an hour of exercises like this looks like a weird kind of fun.

OTs say it’s more than that. Mistrett explained how the tire swing can be used to treat a range of issues—it could help a child who’s too rambunctious, for example, or one who has trouble focusing. According to Mistrett, it hones hand/eye coordination, strengthens trunk muscles, exercises the “vestibular system,” and helps with “motor planning,” or tackling unfamiliar activities.

Yet studies of OT aren’t so certain about its efficacy. Plenty tout the effectiveness of different treatments, but they list caveats that more in-depth research is needed. In 2012, the American Academy of Pediatrics raised skepticism of some sensory-based therapies used in OT—activities such as playing in a pit of balls either to calm or to stimulate a child’s sense of touch—saying they “may be acceptable” for children; “however, parents should be informed that the amount of research . . . is limited and inconclusive.”

Caroline Pendergast of Silver Spring saw OT (including sensory-based therapies) work wonders for her six-year old autistic daughter. Before OT, Margot couldn’t cope with daily activities such as a trip to Target because it meant sensory overload. She had “sudden, huge meltdowns—I’m talking kicking, screaming, collapsing on the floor,” says Pendergast. An OT taught her to put a hat on Margot to decrease visual input from bright lights or have Margot wear headphones to cut down on auditory input from loud and unexpected noise. “I look at OT now as the foundation for everything for us,” Pendergast says, “because . . . if her sensory needs are not met first, then you don’t get anywhere.”

While there are many people, like Margot, for whom OT is effective, there are others—such as handwriting-challenged William—who show little if any benefit. OT, in that way, is a little like psychotherapy. Whether it works depends on a huge number of variables, including how treatment is administered, the child’s development level at the start, and any disabilities he or she may have. And going into it, it’s impossible to know whether your child will be one of its successes. The evaluation will tell you if your child is a little behind developmentally or a lot—that part is straightforward. But it can’t definitively predict whether the issue will resolve itself naturally without therapy.

“If you dig down deep enough on a young child who is in the process of developing,” says psychologist Madeline Levine, author of Teach Your Children Well, “you’re going to find something atypical, and most of these things are outgrown.”

Yet it’s not just children referred by their schools who are ending up in treatment. Some parents themselves are seeking out OT for their kids because they’ve heard anecdotally that it helped another child.

When Vienna pediatrician Michael Martin sees this happen with his patients, it makes him uneasy. Parents who get “the idea that there’s something wrong with my child” start to “treat children differently,” and “that message gets through to the child,” says the board member of Virginia’s chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics. He has watched parents start their son or daughter down the OT path, only to worry then about other developmental problems as well.

Suddenly, Martin says, they’re visiting an OT, a child psychologist, and a speech therapist and “asking for a neurology consult.”

Worrying about our kids is fundamental to parenthood—we all do it. And parents understandably want to help their children thrive, particularly when it seems like no harm will come from giving OT a try. At the same time, the array of local and national pediatricians, psychologists, psychiatrists, and OTs I talked to said that parents who are told that their child’s mild delays warrant therapy should take a step back and think through the recommendation. Have your child’s challenges truly affected his relationships, his ability to socialize, his ability to learn, his ability to be independent?

Or is he mostly okay?

“The way children gain confidence is to make it through their struggles and to realize they did it and that they survived,” says Avy Stock, head of the child-and-adolescent program at the Ross Center for Anxiety & Related Disorders in DC. As good as our intentions may be, we don’t need to fix all of our kids’ issues. At the very least, we should consider the tradeoffs when it comes to OT.

As Michael Thompson tells me: “Do kids in OT move up quartiles in coordination? Almost certainly not. Does it make a difference that he’s getting better at something with a loving [OT]? Maybe. It depends on what he’s missing….Are they not having a play date with a friend? Are they not running around outside?”

Jill Pellettieri (jillhpellettieri@gmail.com) is a former editor at Slate.

This article appears in our February 2016 issue of Washingtonian. Read responses to this article from occupational therapists.