When it opens this fall, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture will aim to tell the entire story of the black experience in America from the 15th century through today, spanning from the origins of the Atlantic slave trade to the Civil War and Jim Crow era to the Civil Rights Movement and all the way through 2016. It will also be, according to Rodrigo Abela, one of the architects consulting on the museum, a “very important building that tells a story to all Americans.”

The Smithsonian gave reporters and photographers a tour of the site Thursday, and while it’s still several months from being ready for its public debut September 24, its the closest glimpse yet of a museum that has been talked about for more than a century. President George W. Bush signed the legislation authorizing the museum 13 years ago, and construction, which started in February 2012, is nearly finished.

Since the building topped out last year, the museum has stuck out from the rest of the Mall thanks to its bronze-colored corona that acts as a shell around the structure. From a distance, it looks like ventilated metal plating, but each of the 3,600 plates that make up the museum’s outer layer are actually inspired by ironwork forged by 19th-century slaves that David Adjaye, one of the museum’s lead architects, saw in South Carolina.

“It’s contextually fitting and is speaking to you from the moment you see it,” he said.

And what’s visible from outside is only half the museum, which goes four stories below ground to the first of its winding history galleries. The tour’s first exhibit, “Slavery and Freedom,” goes back nearly 600 years to when European colonizers first visited Africa.

“How did the slave trade happen?” Mary Elliott, a researcher at the museum, said. “This is the very beginning of the story of slavery and freedom and of power and profit. You will feel this regardless of your race.”

Already installed is a slave shack built in the 1850s in Edisto Island, South Carolina, that was moved piece-by-piece to the museum during the early phases of the construction. Behind the shack are nooks where the Emancipation Proclamation and 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments will be displayed.

As the history gallery gives way to the post-Civil War era, there’s another wooden structure—a log cabin built in the 1870s in what is now Poolesville, Maryland, by Erasmus and Richard Jones, brothers who created a small community of freed slaves on land they purchased after being emancipated. Further up the path there’s a World War II-era plane used by the Tuskegee Airmen suspended from the ceiling.

But there are also many remnants of many of the darkest chapters that followed the Civil War, including Emmett Till’s casket and a guard tower from Louisiana’s notoriously brutal Angola prison. Next to the guard tower will be what exhibit designer Ralph Appelbaum called the museum’s most “hard-hitting” theater. “It’s about violence, the tool of oppression,” he said.

The third level of the history tour runs from the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968 through the present, with spaces reserved for DC’s Resurrection City protest, the Black Arts Movement, the emergence of hip-hop, the Black Panthers, the emergence of the black middle class and changing demographics in cities and suburbs, the election of President Obama, and the Black Lives Matter movement. In particular, the museum built a collection of picket signs used in 1960s and ’70s by various movements, including black feminism and the rise of African-American studies at universities.

In the middle of the building is a space called the Contemplative Court and the Oprah Winfrey Theater, named for the media executive who donated $12 million for the museum’s construction. The wall panels inside the 350 theater mimic the museum’s outer corona.

The four above-ground floors are devoted to education spaces, media galleries, and exhibitions about black contributions and achievements in US culture. Only the top floor, focusing on performing and visual arts, was part of the tour. One exhibit, “Cultural Expressions,” features displays about cuisine, fashion and hairstyles, and social dance and hand gestures. There’s also a section for 20th- and 21st-century visual art featuring works by the likes of Jacob Lawrence, Sam Gilliam, and Kara Walker.

An exhibit called “Taking the Stage” highlights black performers in film, theater, television, and comedy. One display about comedians features six trailblazing joke-tellers: Redd Foxx, Moms Mabley, Godfrey Cambridge, Dick Gregory, Richard Pryor, and, yes, Bill Cosby. (The Smithsonian has said it will acknowledge sexual assault allegations against Cosby.)

Much of the fourth floor, though, is a sweeping collection of artifacts from black musicians dating back from the sounds of the first Africans to be brought to North America to today’s rock and hip-hop. Among the items that will be installed are Marian Anderson’s wardrobe from her 1939 concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial that drew an integrated crowd of more than 75,000, the tambourine Prince used on his 1990 “Nude” tour, and the boombox Radio Raheem carried in Do the Right Thing.

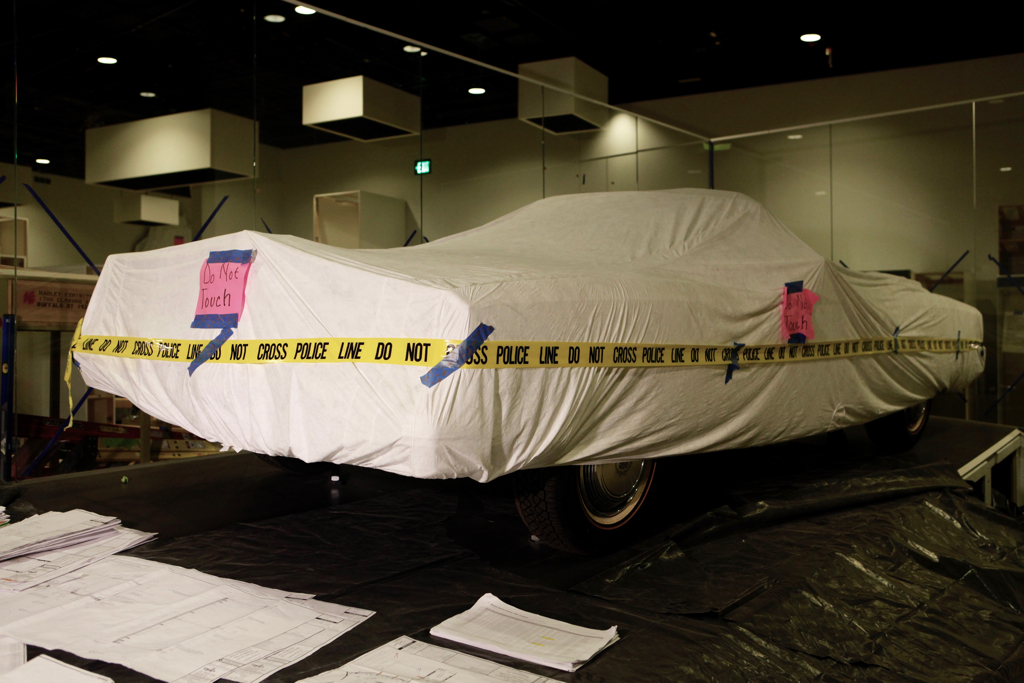

But already inside the music exhibit—though under wraps—are Chuck Berry’s red Cadillac and Parliament Funkadelic’s 1,200-pound Mothership.

“I’m surprised I didn’t hear a question if we had to build a fire-proof roof when we collected the Mothership,” said curator Paul Gardullo in a dad joke.

The early feel is that the whole museum, from its far-reaching history to its celebratory cultural displays, will connect with all visitors when Obama cuts the ribbon on it this fall. “If you think about the world today,” said Phil Freelon, the other lead architect, “you’ll be right back in 1968. Things in these exhibits are happening today.”