“C’mon, Chuckie! Good boy! Good boy!”

An older couple is attempting to walk their Chihuahua at the National Arboretum, and despite their upbeat, doggy-baby-talk voices, the tiny dog is not coming along. Instead, he’s whirling frantically around his owners’ ankles, an odd interpretation of “Good boy!”

Perhaps Chuckie also senses the mortal danger his owners are clearly missing—a danger they would know all about if they were following the year’s most compelling webcam spectacle. About a hundred yards away, a female bald eagle with a seven-foot wingspan and hungry babies to feed has been patrolling the treetops. The pale and rather pleasingly plump Chihuahua is just the right size to be snatched up and hoisted into the sky on razor-sharp, two-inch talons and taken to the nest, to be dismembered and fed to the hungry eagle family before an internet audience numbering in the millions.

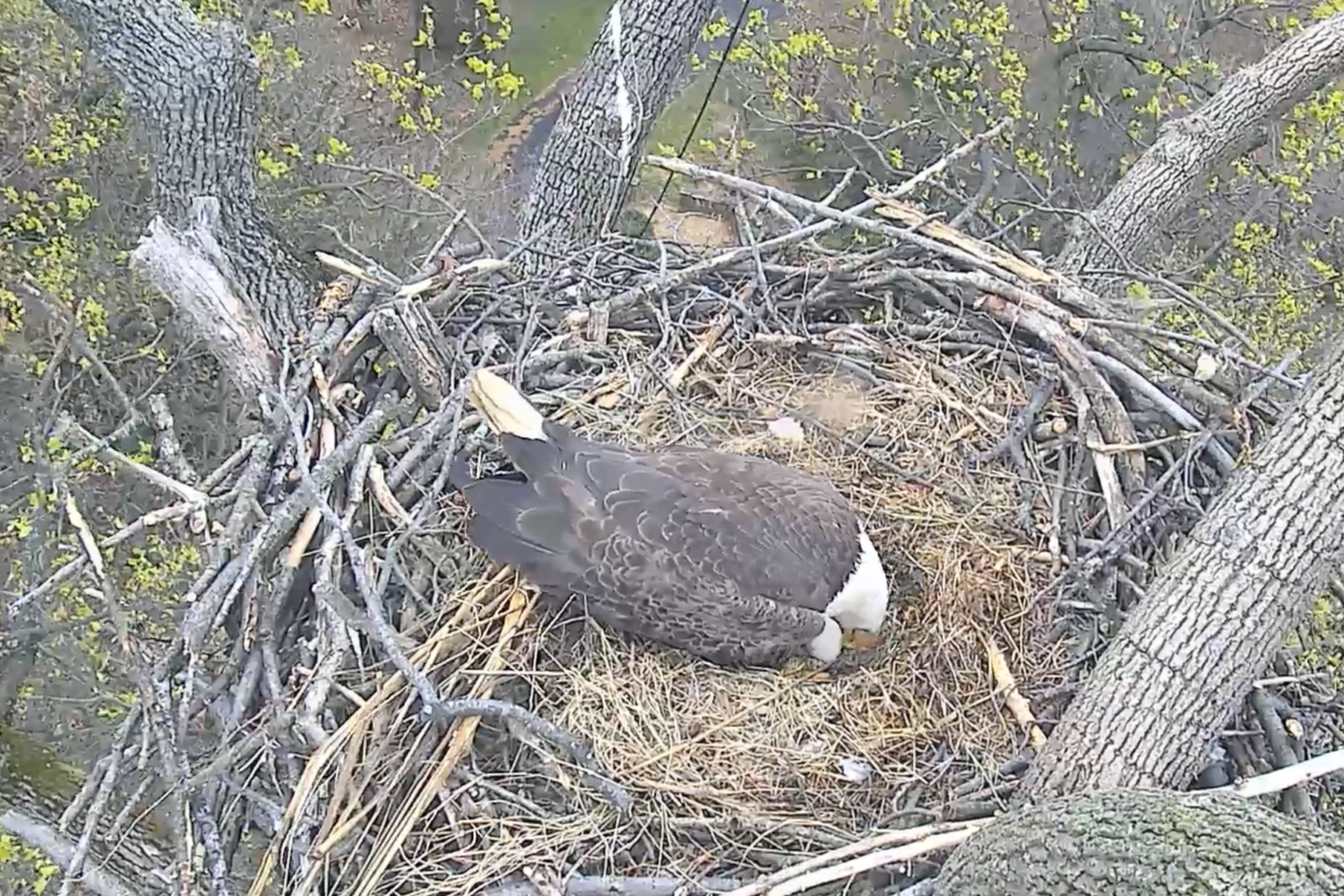

Luckily for Chuckie, I’ve just finished watching the mother eagle through an older technology—binoculars—and “the First Lady,” as she’s known, is busy driving off a marauding hawk, not hunting for tasty small mammals. Meanwhile, her mate—“Mr. President”—remains in the nest, guarding their two young chicks. Since the eaglets hatched on live camera on March 18 and 20, more than 42 million visitors have tuned in to DCEagleCam.org to observe the Arboretum nest and its little gray fuzz balls of love. They’ve quickly become Washington’s new favorite black-and-white internet mascots.

My companions, Bob Nixon and Twan Woods, watch with bemusement. The men know these eagles better than anyone else, because they’re responsible for the birds’ presence in the first place. Along with his wife, the 60-year-old Nixon transported the eagles believed to be Mr. President and the First Lady’s great-grandparents from Wisconsin in 1994. Woods, then a young volunteer for Nixon’s environmental nonprofit, helped raise the eaglets by hand; now 40, he’s been studying them ever since. It was his scope that helped us spot the nest, hidden in the top of a hundred-year-old tulip poplar.

The Arboretum eagles, who showed up last year, are actually the third pair to set up a nest within city limits. The first was established in 1999 at St. Elizabeths Hospital, the second in 2005 at the DC police department’s training academy. The police-academy eagles, Liberty and Justice, also have a pair of chicks, who hatched about a week after their Arboretum cousins in late March and soon got their own webcam, too. They also seem to be quite well fed. “At the police-academy nest one time, the dad brought back a cat,” says Nixon. “I said, ‘Did it have a collar?’ ”

Luckily, this happened before the police-academy nest went online. (It was delayed by bureaucratic infighting and interagency turf wars—this is still Washington, after all.) So the grisly feast went unwitnessed. Their webcam can now be found at EarthConservationCorps.org—even DC police chief Cathy Lanier keeps it open at all times on her phone. “I show it to everybody,” she says. “It’s incredible.”

It’s safe to say that almost nothing happens in Washington by accident, and that’s true of the eagles as well. They didn’t just show up and build nests. They’re here by design, and their presence tells a larger story—about the rebirth of the Anacostia River, one man’s lifelong obsession, and the headlong evolution of a city where everything seems to be changing, except for the things that remain stubbornly the same.

• • •

During his senior year at Duke Ellington School of the Arts, Twan Woods ran into a friend who said he was earning some spending money by picking up trash and old tires from local creeks.

Woods was studying voice and hoping for a music career, but the cash sounded good, so he joined Earth Conservation Corps, a brand-new environmental group working in the eastern part of DC.

Along with a handful of other young people, Woods spent his weekends and summer vacation working on cleanup projects throughout the Anacostia watershed. It felt good to clean up the neighborhood where he’d grown up amid poverty and drug-related violence. More important, he met Nixon, who had an unusual résumé for an inner-city environmentalist, to say the least.

Bob Nixon had been a Hollywood film producer with a house in Malibu and an Oscar nomination when he moved to Washington. He could have written his own ticket in the film industry. Instead, he decided to save a river that until then he’d only read about. He had to, he tells me, because of a promise he’d made to Dian Fossey, one of his lifelong heroes.

He’d met Fossey in Africa while filming a documentary. “When we told her she ought to make a movie about her life story, she was like, ‘Shut the f— up,’ ” Nixon says. “She was hard to film, because every other word out of her mouth was a swear word.” Eventually, she changed her mind, and better yet, she didn’t want money in exchange for her story. Instead, she wanted Nixon’s time. “She said I had to do a year of ‘boots on the ground’ conservation work,” he recalls. “Not filming.”

Bob Nixon had been a Hollywood film producer with a house in Malibu and an Oscar nomination. He could have written his own ticket in the film industry. Instead, he decided to save a river in Washington.

Nixon agreed, only to discover that nobody in Hollywood was interested in the tale of a woman who lived in the jungle with gorillas. That changed after Fossey was murdered in 1985. Suddenly, everyone wanted her story. The result was the hit Gorillas in the Mist, starring Sigourney Weaver. After the buzz died down, Nixon knew he had to keep his promise. But just where to put those boots on the ground?

He’d seen a New York Times article about a tiny creek called Lower Beaverdam, in far Northeast DC. Located beside the Amtrak rail line and US Route 50, Lower Beaverdam was basically a ditch filled with used tires, discarded appliances, and tons of trash. It fed into what was probably the most neglected urban waterway in America: the Anacostia.

Protruding from the Potomac like a sore appendix, the Anacostia is really more of a muddy estuary than a proper river. What that means is that pollution doesn’t get swept downstream very efficiently; instead, it stays around, sloshing back and forth with the tides. Even more, though, the state of the river was symbolic of DC’s deeper social and economic dysfunction, dividing the prosperous federal core from some of the nation’s poorest, most violent neighborhoods.

Nixon knew little of this local history—he’d grown up on the Main Line outside Philadelphia. But he’d read about a proposal from the first Bush administration that intrigued him. “They were going to hire a million inner-city kids to plant a billion trees,” he says. It would be called Earth Conservation Corps, kind of like an urban, environmental Peace Corps.

It never happened, so Nixon took the name and set up shop on DC’s forgotten river. He met with community organizers, including Brenda Richardson, who worked with kids at the Valley Green housing project. “You could tell he was passionate,” Richardson remembers. “He said, ‘I want the kids that nobody else wants.’ ”

He ended up with nine teenage volunteers, all from Valley Green, and a small amount of funding from the Coors Foundation and his own pockets. Plus his unshakable faith. “There was so much f—ing talent and promise in this group,” he says. Job one was to go and clean up Lower Beaverdam, the creek he’d read about in the Times. Starting in April 1992, he and his volunteers pulled 5,000 tires out of the creek in three months, earning some nice press from the Washington Post. Mission accomplished—or so he thought.

But then tragedy struck, and a one-year promise to a dead environmental treasure turned into a nearly 25-year journey.

• • •

“That’s what I like to see,” Nixon says, peering into a hatch on the Corps’s 30-foot flat-bottomed aluminum skiff. “Paddles.”

Uh-oh. Seems there have been some engine issues lately. But the big Mercury outboard roars to life, then purrs happily as we cast off from the dock of the Pumphouse, a blocky brick structure practically in the shadow of Nationals Park.

Decades ago, the building was used to pump water to irrigate the grounds of the US Capitol. But the water got too polluted and the structure sat empty. When Nixon spotted it in the ’90s, it was “covered in guano,” he says. This was before the baseball team, before the baseball stadium, and well before anyone imagined the neighborhood as a place to lure Washington’s affluent. The city leased the building to him for a dollar. Now cleaned up and refloored, with exposed brick, river views, and a giant pulley assembly dangling overhead, it’s pure industrial chic. As we leave, a hipster chef is planning the details of a pop-up dinner party there.

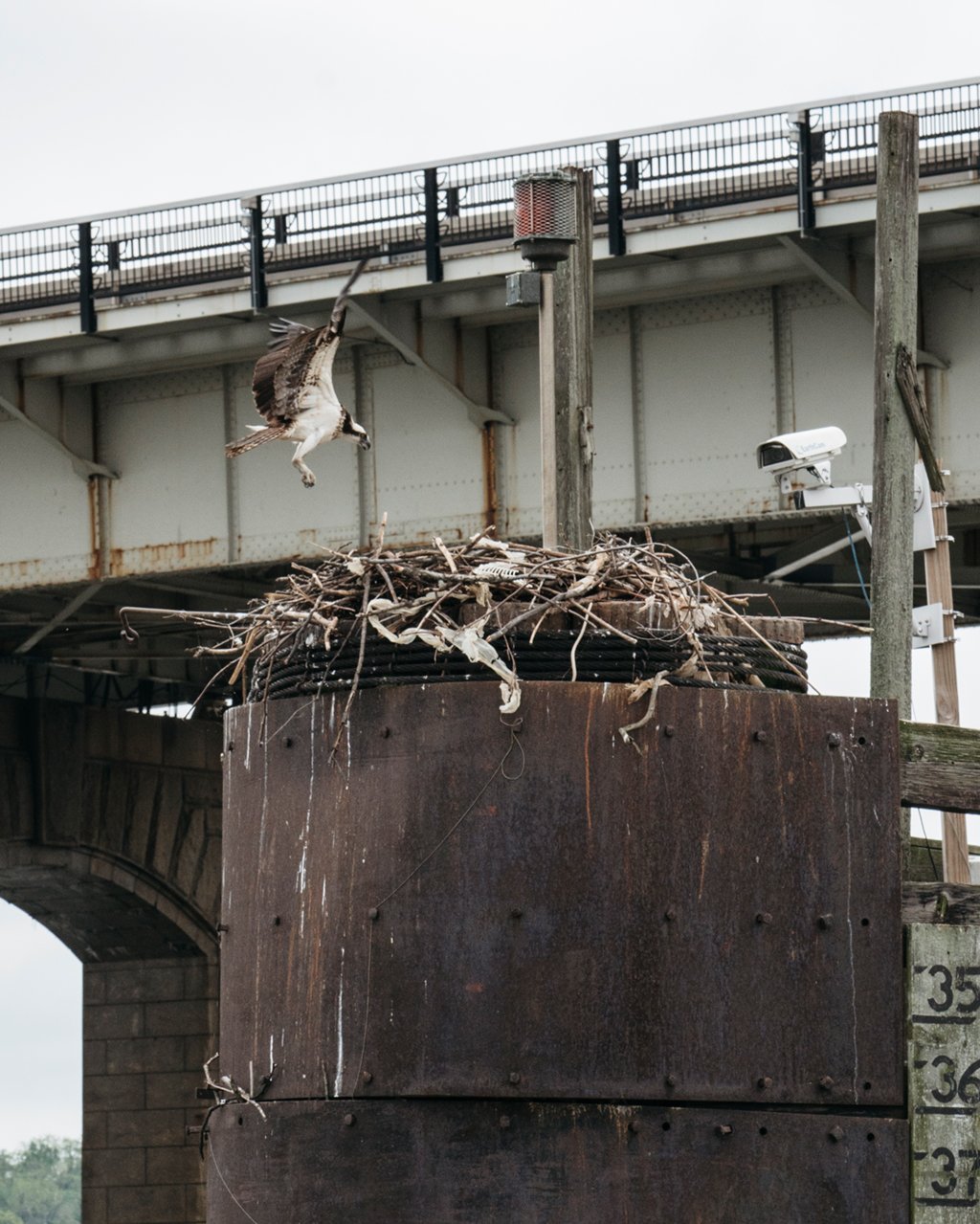

We’re on an afternoon cruise down to the Potomac, then back up the length of the Anacostia. As we swing into the main channel of the river, it doesn’t take long to spot the first birds: a pair of ospreys nesting on the Frederick Douglass Memorial Bridge. They, too, are on a 24-hour wildlife camera. (There are 19 other active osprey nests locally—up from zero 30 years ago.)

With sandy blond hair and a nicely antiqued blue Vineyard Vines pullover, Nixon is handsome on the way to craggy. Turns out he and his wife, Sarah Guinan Nixon, own a home on the real Martha’s Vineyard, as well as an inn. He was there yesterday, in fact. But that seems like another life right now. “He’s like a 19th-century explorer,” says his old friend Robert F. Kennedy Jr. “He’s been everywhere.”

It’s uncomfortably chilly for late April, and the sky threatens rain. At the helm is Mandy Nativi, a 24-year-old ECC intern who handles the group’s migratory-bird projects. She’s interested in the ospreys, the kings of migratory hawks. One, nicknamed Rodney, was tracked via GPS on a journey that took him from the Douglass Bridge all the way to the jungles of Venezuela, a 3,500-mile journey—in six days. But Rodney isn’t in the nest anymore. He was hit by an airplane at Reagan National Airport a year ago, and his mate promptly replaced him. So it goes.

Nativi steers us up the channel, past the Navy Yard and the gray hulk of the USS Barry (named for the commodore, not the mayor). On our left, we pass two dilapidated-looking boat clubs; on the right are parkland, freeways, and the Fairlawn neighborhood. I discover that this is Nativi’s first time driving the boat—and, as she’ll later admit, “my second time in a boat.”

Nevertheless, she manages to thread us through the narrow gap in the low CSX railroad bridge just as a train clanks over our heads. The bridge has effectively barred most boat traffic and development upstream, and we emerge into what seems like an entirely different continent. The city has faded to the background. Soon, even the distant outlines of RFK Stadium and DC General are eclipsed by the trees arching over the muddy water. We could be in Vietnam or Venezuela. Well, except for the Metro tracks and the Ethel Kennedy Bridge, which carries Benning Road, Northeast, across the river and is named after Nixon’s most influential patron and board member. The Kennedy matriarch gave more than money. “She took tires out of Lower Beaverdam Creek alongside pioneer Corps members,” says Sarah Nixon. “She visited families when their children were murdered.” Everywhere else we look, it’s green.

“It’s a whole different river,” says Nativi.

“But it’s in the heart of DC,” says Nixon.

Now we’re passing Kingman Island on our left. “That’s where I got handcuffed to a tree,” Nixon says. In 1998, he and a group of his kids had knocked down a National Park Service fence with a bulldozer and scooped up huge mounds of trash that had been dumped there illegally. They left a couple hundred pounds of wildflower seeds. When Nixon went back the next day to assess their progress, cop cars converged on him. “They charged me with stealing trash,” he laughs. His motto: “Don’t stop until they stop you.”

Suddenly, a muscular-looking bird comes flapping in over the treetops. “That’s Tink,” Nixon says. “He likes to hunt here.” Tink was one of the first eagles to take up residence in DC, nesting near the former St. Elizabeths, and thus is not on a webcam. Perhaps spooked by us, he flaps away, heading upstream.

Nixon and Nativi are surprised by none of this, but I am. Twenty-five years ago, I put a canoe in the river with a photographer friend and paddled upstream, intending to write about the city’s neglected “other” river. We saw floating rafts of trash and hundreds of tires that day—but also plenty of herons and one enormous snapping turtle that remains the largest I’ve ever seen.

Though the water was a viscous gray-brown broth and there were a fair number of belly-up fish, including a large dead catfish, we also saw even more fish jumping and finning the water’s surface. I remember being moved by the whole slightly smelly scene, and I came home and wrote a 10,000-word ode to the resilience of nature. I had no idea.

“I’ve seen most of the rivers in the East, and that was the deadest of them all,” says Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who toured the Anacostia with Nixon early on and helped him establish Anacostia Riverkeeper, an advocacy group focused on improving water quality. “It was literally dead—there was nothing in it.” They cast a 100-foot fishing net into the water and came up with exactly three fish—all of them migratory shad, which didn’t even live there full time.

The water is a lot cleaner now, although there are a number of floating plastic water bottles. Nixon points out one of six “trash traps,” basically a large fishing net around a major storm-sewer outfall, meant to catch debris that gets washed off city streets in rainstorms. Our boat is long and low, perfect for seating dozens of kids on field trips—more than 30,000 DC public-school children have visited, according to Richardson, now ECC’s managing director—or carrying a few hundred pounds of garbage.

Not only that, but today we’ll see three hunting eagles, including Mr. President, who takes his customary perch in a tree. That means there must be plenty for them to eat now, too. Later, my 11-year-old niece, watching via webcam in New Jersey, will text me to report, “I just saw the mama bring fish to the babies!”

Around a bend, another once-unlikely craft comes into view: an eight-woman rowing shell from the boathouse at Bladensburg, a few miles upriver. One shell becomes half a dozen, and we kill the engine to let them pass. Even more astonishing is that a brand-new bicycle path is under construction on the east side of the river. By this fall, it will be possible to ride from College Park to Nationals Park all on dedicated bike paths. Workers are also finishing a sweet-looking bridge spanning Lower Beaverdam Creek, where it all started.

In July 1992, three months after ECC first set foot in Lower Beaverdam Creek, they were invited to Houston for that year’s GOP convention. The volunteers were to be showcased as one of President George H.W. Bush’s “thousand points of light.” While they were in Texas but before they could enjoy their moment in the spotlight, one of them, 19-year-old Monique Johnson, was raped and murdered in a bizarre and random crime.

“That was the beginning of our trail of tears,” Nixon says. Within months, another kid was killed—and another. Of the nine original class members, four are now dead: three murdered, one from untreated diabetes.

“Bob came from Malibu to the hardest part of the nation’s capital,” Woods had told me a few days earlier. “He’s a white guy, and he’s coming to the hood! Then he takes the children to Texas—and one of them don’t come back! Bob could have given up right then.”

But he didn’t. He sold the house in Malibu, moved to Washington, and recruited a second group of kids, including Woods. At their urging, he put cameras in their hands to document what they were doing. As one put it, “Nobody’s going to believe we had our black asses in this creek.”

Then Nixon came up with an even crazier idea than turning inner-city kids into environmental foot soldiers: bringing back the eagles.

• • •

Before he was a Hollywood guy, Bob Nixon was a bird guy.

His wife remembers their first (blind) date. He cooked her dinner. “I went to get some ice from the freezer,” she says, “and there was this roadkilled owl staring back at me.”

The date was a success anyway. As the daughter of legendary DC activists Ed and Kathleen Guinan—who founded the Community for Creative Nonviolence homeless shelter—Sarah was used to being around passionate, slightly eccentric people. Although she was only 22 at the time and he was nearly 40, they got married within eight months. They now have three teenagers and live in Georgetown.

As for the owl, it was destined to be stuffed and mounted—turns out Nixon’s only degree is in taxidermy. Growing up, he’d been an indifferent student with what we now call learning “challenges.” “He was dyslexic, he was dysgraphic, and the teachers all but wrote him off,” says Sarah. He lasted a few months at college. “I told my mother, ‘I went to college!’ ” he laughs. She wasn’t amused.

Nixon’s father was a Chrysler executive, but his mother, Agnes Nixon, was the real breadwinner: She created and wrote the soap operas One Life to Live and All My Children. “She was a brilliant writer,” he says. (She’s still alive, at 90.) Her son was clearly headed for a different career track—he loved birds and loved photography. So instead of college, he went to England to study falconry.

There weren’t many raptors in Washington in 1992. The last bald eagles had left the Anacostia in 1947. It was the same story around the country, as bald-eagle populations collapsed, largely because of pesticides such as DDT. By the 1970s, the bald-eagle population was down to a few hundred breeding pairs nationwide, most in the Northwest and upper Midwest.

But the population slowly began to recover nationally, and Nixon was quick to see that the birds could be of great value as a symbol of hope and change. In 1994, he persuaded the US Fish and Wildlife Service to give him permits to bring young eagles to Washington, and he convinced the Department of Agriculture to allow an artificial nest to be set up at the National Arboretum. “He was relentless,” remembers former Agriculture Secretary Dan Glickman. “My staff would say, ‘Bob Nixon’s on the phone,’ and I’d be like, ‘Not again.’ ”

Glickman ultimately agreed, and Woods’s group of ECC kids hauled the first “hack box,” a kind of wooden cage/nest, up into a scraggly-looking oak tree by the riverbank. Into the box went the first two pairs of eaglets, to be fed by volunteers until they could fly on their own. Woods and the others hid in the bushes and hoisted buckets of fish up to the nest. “We didn’t want them to see us and think we were their parents,” Woods says. “Fish from the sky was all they knew.”

Woods took to the birds. “Once I started learning about these eagles and ospreys,” he says, “I just fell in love.”

The eagles were tagged with identification bands, and eventually they were ready for freedom. Glickman had the honor of opening the cage doors and letting them go. Two were named Monique and Tink, for Monique Johnson and Gerald “Tink” Hulett, another Corps member who was murdered, in 1996.

Things didn’t always go smoothly for the young birds. As Woods puts it, “Flying is easy—it’s landing that’s hard.” When a young eagle crash-landed in the river, Nixon and a crowd of teenagers happened to be watching from Langston public golf course. He jumped in, swam across, and pulled the bird, which was starting to drown, out of the water. It then got itself entangled in a tree. Nixon borrowed a seven-iron to free the creature. “Then he went flying down the fairway, whoop-whoop-whoop, so it ended up perfect,” he says.

They did the same thing for the next three years. Between 1994 and 1997, Woods and his colleagues raised eight pairs of birds in that Arboretum hack box. After they were released, they were fed raw fish from platforms set up in the river, until they learned to fly on their own. Eventually, they all flew away in search of their fortunes.

Where they went is anybody’s guess. Bald eagles reach maturity, with their signature white feathers, at five years; they’re known to live to 15 years and maybe longer in the wild, where they have few predators. It’s a good sign, Woods and Nixon think, that none of the bands has ever been returned—meaning none of the birds has been confirmed killed. One of their banded eagles was found by a trucker beside Interstate 80 in Pennsylvania a few years ago, sick with parasites but still alive. The bird was treated and released back into the wild. That’s the only confirmed sighting.

The birds did better than the humans. As you enter the Pumphouse, you pass a wall of honor, commemorating ECC members who have been killed. There are a dozen plaques, with photos. Monique and Tink were only the first. Twenty-six young people who worked with the Corps have been murdered; their names, their writings, and programs from their memorial services fill a thick binder in the office. “I’ve stopped counting,” says Nixon.

Perhaps the most painful was the loss of “Diamond” Teague, a 19-year-old honor student and musician whom everyone loved and who was killed on his front porch in 2003. The riverbank park by the Pumphouse is named after him.

A few years ago, it got to be too much for Nixon: “My kids said, ‘Dad, you’ve stopped talking.’ My daughter told me, ‘When I was seven, Diamond Teague was my hero.’ ”

Nixon had to step away, so he went off and made a documentary, Mission Blue, about the life of oceanographer Sylvia Earle. The organization foundered for a while. Now, with Nixon back and Brenda Richardson as managing director, it’s on the way to thriving again. There are currently five Corps leaders, plus others like Woods who come back to pitch in.

“They’ve been a great partner,” says John Mein, head of community outreach for DC’s Department of Public Safety. ECC has been working with the department’s Youth Creating Change program. “It says something about Washington that we’re able to have multiple pairs of eagles calling the city their home. It’s not just the health of the river but the health of some of the communities that Bob and ECC work in.”

“I think it was a brilliant idea,” says police chief Cathy Lanier. “He’s like the humblest guy, for as accomplished as he is and all they could be doing, they focus on protection of the birds—the most vulnerable birds and the most vulnerable people.”

As for the eagles, they’ve been taking care of themselves. In 1999, five years after Monique and Tink were released, the first mature bald eagles began to build a nest in the District, for the first time in more than half a century. They didn’t nest on the Potomac or in Rock Creek Park—they picked Ward 8, in the poorest part of the city, and began raising their young there, year after year. They had to be Monique and Tink, Nixon and the kids decided, returned home to roost. The others followed suit, all in Northeast and Southeast.

Says Woods: “They’ve come back to the people that raised them.”

Bill Gifford is the author of “Spring Chicken: Stay Young Forever (Or Die Trying),” a personal investigation into the science of aging. On Twitter, he’s @billgifford.