A map of the District showing the spots that draw in Pokemon Go players doesn’t just tell where all the Pikachus and Charizards are hiding. It also underscores the demographic divisions across city neighborhoods, according to researchers at the Urban Institute.

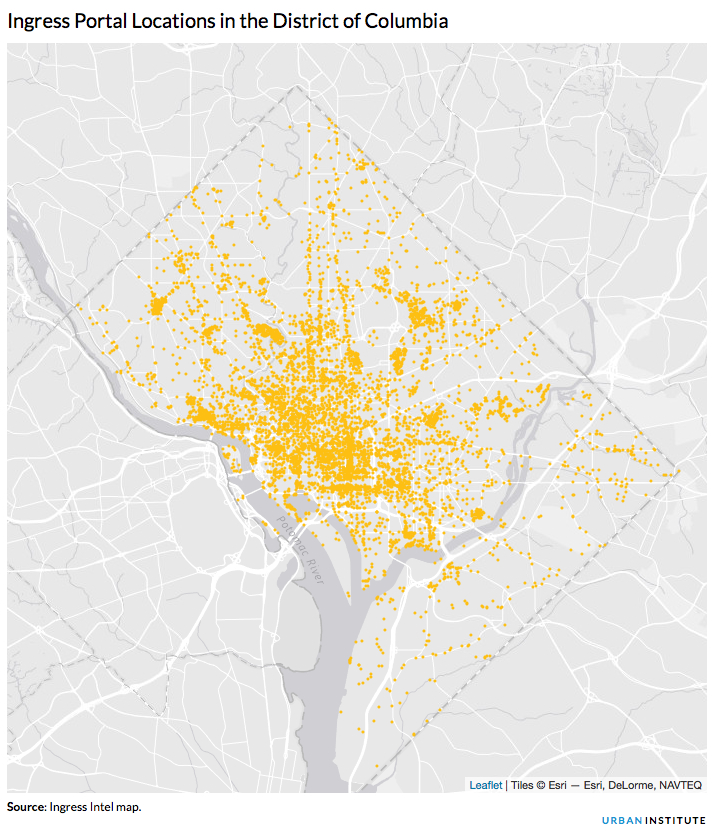

Pokestops, the locations where players capture the cartoon monsters, and “gyms” where the creatures are trained up, tend to be concentrated around parks, popular stores and restaurants, and other landmarks. In the District, the heaviest concentration of Pokemon Go hotspots can be found around the Mall, Dupont Circle, Georgetown, and other neighborhoods with lots of gathering spots. And the parts with the greatest concentrations of Pokemon-connected locations tend to be DC’s majority-white neighborhoods, while majority-black neighborhoods have far fewer places where users can catch one. East of the Anacostia River is a relative Pokemon desert, according to this map:

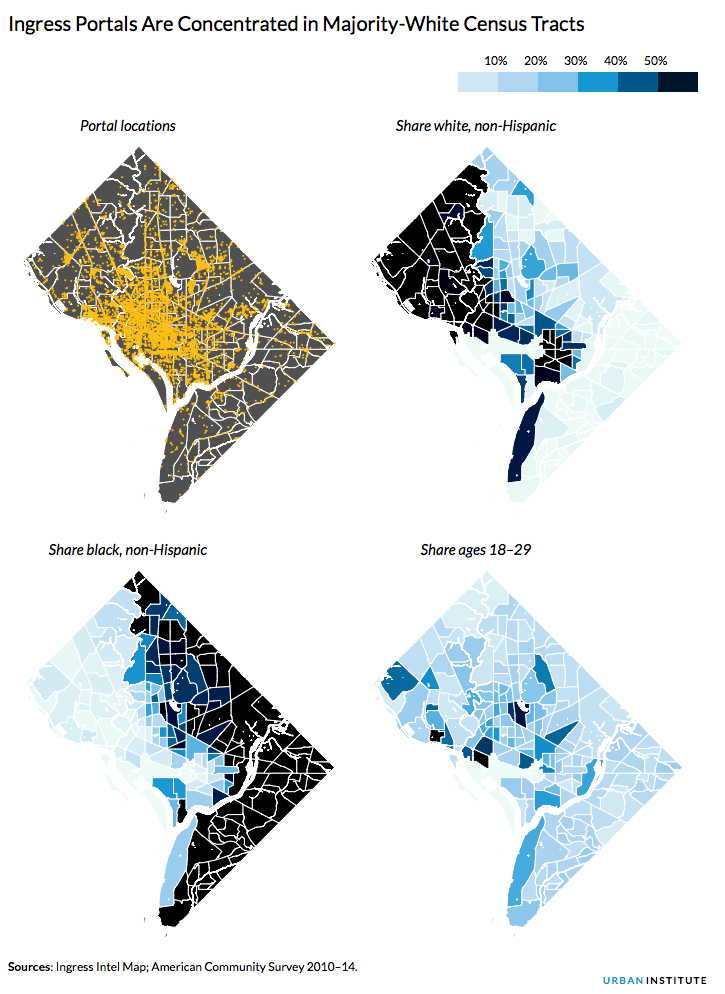

“Pokestops and gyms are abundant in predominantly white neighborhoods,” the researchers, Shiva Kooragayala and Tanaya Srini write. “Even when accounting for population density and the percentage of millennials at the neighborhood level, we find that as the share of the white population increases, Pokéstops and gyms become more plentiful.”

The uneven distribution of Pokemon Go locations can be largely attributed to its underlying technology. The game’s publisher, Niantic, developed it from its previous “augmented reality” game, Ingress, in which players marked up real-world maps with crowdsourced “portals” until Niantic stopped taking new submissions last September. Ingress’s fan base was made up largely of white, English-speaking men, resulting in that game’s map being tilted toward business- and tourist-heavy areas.

When Niantic built Pokemon Go, the portals Ingress players left were transformed into Pokéstops and gyms, resulting in the map players face now. Pokemon Go’s data isn’t available, but Kooragayala and Srini read Ingress’s map of “portals” and found that DC’s majority-white neighborhoods contained an average of 58 Pokestops and gyms, while majority-black neighborhoods averaged only 26 Pokemon locations.

Even when adjusting his analyses to account for income levels and age distribution—and discounting the activity around the Mall—Kooragayala finds that the proportion of Pokemon Go action taking place in majority-white neighborhoods is just as pronounced.

While Kooragayala doesn’t fault the publisher, his analysis can be instructive in what Pokemon Go says about placemaking in cities. Similar patterns have been seen in Detroit, Boston, and San Francisco, where Pokemon Go maps also show an abundance of hotspots in majority-white neighborhoods, while parts of those cities with fewer parks, businesses, and other communal spots are populated (by little cartoon monsters) more sparsely. Fusion calls the effect “Pokémon redlining,” a reference to discriminatory housing practices against minorities and poor people.

But because Pokemon Go fundamentally is a game that requires its users to go outside and walk around, Kooragayala says the game could lead to better placemaking where it is lacking. “Pokemon has this great potential for placemaking, and it’s really about creating a sense of place and community,” he says. “What we were really looking at was if everyone in the city has been able to participate in an equal way. That’s not really the case.”

Guides to catching Pokemon in Washington almost uniformly tell players to hunt around the Mall and the neighborhoods closest to downtown. Of the 24 locations included in a map by Curbed, the one farthest from DC’s urban core is located at Monroe Street Market, an upscale residential and commercial development in Brookland.

Building and improving public spaces can improve business, cultural, and tourist activity in neighborhoods and often leads to reduced crime rates, increased pedestrian traffic, and improved public health, according to urban planners like Kooragayala. Pokemon Go, at its best, could be an engine for improvement if its publisher starts allowing users to create new locations like it did with Ingress.

“When we live in these segregated communities there isn’t much interaction between neighborhoods,” he says. “When you’re battling you’re encountering different people. Like when you go to a park and everyone’s experiencing a space the same way.”