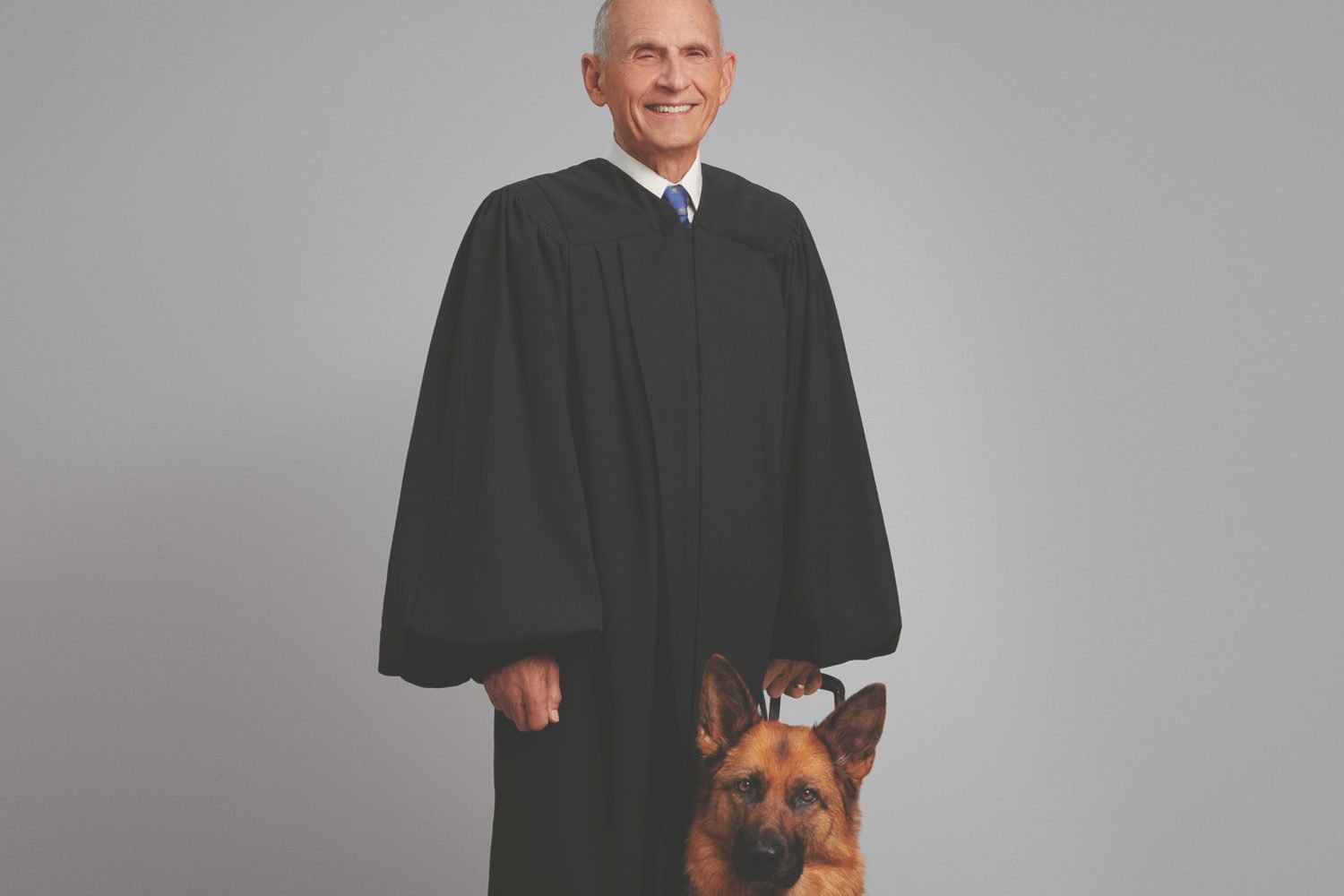

Richard Roberts—better known as “Ricky”—has had the ultimate Washington legal career. He was a longtime federal prosecutor. He worked for Covington & Burling, one of DC’s most powerful law firms. In 1998, President Clinton appointed him to the US District Court for DC, among the most influential benches in the country. In 2013, he became its chief judge.

Perhaps most famously, Roberts and fellow prosecutor Judith Retchin were the DOJ stars of the 1990s who sent Marion Barry to prison for smoking crack.

Yet throughout his rise to the pinnacle of Washington’s hyper-competitive legal food chain, Roberts, it turns out, was keeping a secret—the kind of secret that may have halted that ascent altogether.

A little over 35 years ago, Roberts had a sexual relationship with a key witness in a headline-making case—the trial of a racist serial killer in Salt Lake City. Roberts was one of two federal prosecutors who tried the case, and he has said it was among the most important of his career. He was 27 at the time of the trial. The witness was 16.

Now, the witness, a woman named Terry Mitchell, has filed a civil lawsuit against Roberts that accuses him of raping her. In court filings, Roberts’s lawyers at Steptoe & Johnson—including top white-collar defender Reid Weingarten—called Mitchell’s allegations “categorically false” and stated that the two had “a brief, consensual intimate relationship after her role in the Franklin trial ended.” Roberts declined to comment for this story; in a statement his lawyers called the relationship “a bad lapse in judgment.” He has not been criminally charged; in Utah at that time, the age of consent was 16.

Yet the revelation of the relationship has seemingly brought a sudden end to the federal judge’s illustrious career. He stepped down from the court at age 62, the same day Mitchell went public with her accusations and $25 million law suit against him. Roberts also finds himself facing questions about his ethics; he is the subject of an ongoing judicial misconduct investigation that was personally green-lit by Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts.

It’s a remarkable fall for a lion of local legal circles. As Edward Williams, a former law clerk for Roberts, puts it: “He’s someone who, but for this allegation, might have had the next annex of the District Court building named after him, or, I don’t know, some hall at the Department of Justice.”

• • •

In the fall of 1980, Roberts was a civil rights lawyer for the Department of Justice in Washington. It was a dream job for a young and politically active African-American lawyer who came of age during the civil rights movement and was only a couple years out of Columbia Law School. One night that October, he had just settled in with a bag of popcorn to watch President Jimmy Carter debate his Republican challenger, Ronald Reagan, when he got the phone call that would help lay the foundation for the rest of his career. He was being sent to Salt Lake City to try a case against one of the worst serial killers in US history: Joseph Paul Franklin.

Franklin was a white supremacist who terrified the nation by gunning down blacks, Jews, and people who associated with them, and who was ultimately blamed for 22 murders. In 1978, he shot and paralyzed Larry Flynt because the Hustler publisher’s magazine showed interracial sex; in 1980, he shot Washington lawyer and civil rights activist Vernon Jordan, Jr. as he exited a car driven by a white woman.

Franklin had shot and killed two young black men in a park in Salt Lake City, and DOJ had brought a civil rights case against him that rested on an unusual statute. It was Roberts’s and co-prosecutor Steven Snarr’s job to prove Franklin had targeted the victims because of their race, and because they were using a public park. “It was a novel legal issue,” recalls Barry Kowalski, a colleague of Roberts’s at DOJ who later tried the Vernon Jordan case against Franklin. “Rick was the kind of intellect you needed.”

Terry Mitchell was a friend of the men who died. She witnessed the slayings at such close range that she was hit with shrapnel, making her testimony critical to the government’s case against Franklin.

When she met Roberts for the first time, she made an impression he’d remember for decades. “When we saw each other, our eyes, I think, both sort of lit up,” Roberts said in a recorded phone call with Mitchell in 2014. “I didn’t know if…your eyes were lighting up because this was your opportunity to convey to, you know, the Washington people, who were going to put together this case, uh, what you had been through or something else. But…I saw that, I held that. I wasn’t certain, you know, of what was transpiring, and I was quite anxious, and interested in this person that I saw.”

The 27-year-old prosecutor was well over six-feet tall, a Vassar grad who had been a serious pianist and singer, and attended the prestigious High School of Music & Art in New York City. “The movie Fame was big back then,” Mitchell remembers. “He kept telling me he went to that high school.”

“He was someone who I think people watched,” says Theodore Shaw, who went to law school with Roberts and worked with him at DOJ. “He was this good-looking guy who stood out . . . I don’t think he’d get lost in a room anywhere.”

Sixteen-year-old Mitchell, by contrast, was a survivor of sexual assault. About two months before watching her friends get shot in the Salt Lake park, she was raped by a stranger in an attack that lasted hours. (Her assailant pled guilty.) Before that, she says, she was sexually abused by several men, including a relative, from the time she was a toddler.

To a traumatized girl from a poor family, Roberts was a dazzling presence. “I had never met anyone like him,” she tells Washingtonian. “I’d read about people like him. I’d seen them in the movies. But I’d never seen anybody that well dressed, that stylish, so dripping with charm.”

• • •

The alleged assaults began in late January or early February of 1981, according to Mitchell’s lawsuit, once Ricky Roberts was stationed in Salt Lake City semi-permanently to focus on trial prep. On the night Mitchell says she was first raped, her mother drove her to the courthouse to go over her testimony. After some discussion of the case, Mitchell alleges Roberts took her out to dinner, where he squeezed in next to her in a small booth and touched her thigh. After the meal, the suit states, Roberts stopped at his hotel before taking Mitchell home. She alleges that she asked to wait in the car, and then the lobby, but that Roberts kept pushing her to come upstairs.

When Roberts “finally had Mitchell in his hotel room, against her will, he locked the door, took off her jacket, began kissing her neck, and said, ‘You aren’t going anywhere until I get a taste of you,’ ” the complaint reads.

Mitchell alleges Roberts demanded oral sex, then raped her twice. The suit states the abuse continued like that for several weeks, “nearly every day,” with Roberts picking her up from home or the courthouse, taking her to dinner, and then back to his hotel. Roberts, who was not married at the time, characterized the relationship as “an affair,” Mitchell’s suit states, and said “he could not stop himself because of how attractive [she] was.”

Karma Jones, a friend of Mitchell’s and the other eyewitness to the murders, told state investigators in Utah in 2014 that Mitchell said Roberts “was going to make sure that she was OK getting through the court proceedings . . . and . . . he was her boyfriend because they were having sex.”

Roberts “exploited the psychological and emotional vulnerabilities of sixteen-year-old Mitchell who, as Defendant Roberts well knew, had experienced a lifetime of sexual abuse, grooming, violence, and rape,” the lawsuit reads. “Defendant Roberts maintained the secrecy of his abuse by using intimidation, deception, artifice, and the coercive, victim-blaming threat to Mitchell that if anyone discovered Defendant Roberts was engaging in sex acts with Mitchell, then a mistrial would occur.”

Mitchell’s mother, Carolyn Gentry, told Utah investigators in 2014 that she grew suspicious of all the time her daughter was spending with Roberts at dinners and his hotel. “It seemed like right before the trial it was bang, bang, every night she was there,” Gentry stated. Mitchell ultimately told her mother that the two were having sex. Gentry—then a single parent working three jobs—didn’t interfere. “I think I was intimidated by his position,” she told investigators. “You know, you just, someone with authority, you just kind of let things be.” (Gentry died in 2015.)

The trial began on February 23, 1981. The night of her testimony, Mitchell says she was back at Roberts’s hotel. She alleges he angled the television so he could watch the local news coverage of the day’s proceedings while they were in bed together.

• • •

The jury took only 14 hours to find Franklin guilty. “A big win,” says Daniel Rinzel, then Roberts’s boss at the Justice Department. Roberts returned to DC, primed for his sensational career. Friends say he never mentioned the young woman he’d slept with in Salt Lake. “Not a word,” says Shaw, who’s now director of the Center for Civil Rights at the University of North Carolina School of Law. “Think about how that conversation would’ve gone. There are a lot of reasons he couldn’t have that conversation.”

Mitchell, meanwhile, married a marine, moved to Quantico, and had her first child when she was 20. In 1985, she says, Roberts tracked her down, and the two spoke by phone. “He asked me if I ever thought about him,” she tells Washingtonian. “He asked me if I ever thought we could be together.” She says she explained she was married with a newborn, and the call ended: “It was brief, and polite, and confusing.”

Five years later, Roberts was an assistant US Attorney for the District, making front-page news for prosecuting Marion Barry. During opening statements of the mayor’s criminal trial, according to the Washington Post, Roberts “transfixed” the courtroom by pantomiming how Barry had dragged on his infamous, caught-on-tape crack pipe: “He held the imaginary hit eight seconds, nine seconds, 10—an eternity—then blew it out. …In a dozen ways the demonstration could have gone awry, but Roberts pulled it off without a false note.”

By 1998, Roberts was up on Capitol Hill for his judicial confirmation hearing in the Senate. He sailed through the lawmakers’ run-of-the-mill questions, and introduced his family, including his wife, Vonya McCann, an exceptionally accomplished attorney in her own right who was an ambassador and deputy assistant secretary at the State Department during the Clinton administration.

Mitchell had no idea Roberts had become a judge. That was, until two or three years later, when she says he found her again. By then she was a real-estate agent, and a divorced mother of two. She says she and Roberts hadn’t spoken since that strange 1985 call, and this conversation was even weirder. She says he asked questions about her life—how many kids did she have?, what did she do for a living?—but whenever she attempted to answer, he cut her short.

“He’d say, ‘So we’re good, right?’ ” she says. “‘So, we’re good, right?’ ”

She didn’t know what he meant.

• • •

The next time Mitchell says she heard from Roberts was right after Franklin, the serial killer, was executed. It was November of 2013, and Roberts emailed her to share the news. This time, the correspondence sent her reeling.

The resurfacing of old wounds prompted Mitchell to revisit whether her relationship with Roberts actually had been an “affair.” She had always remembered that she and Roberts had a sexual relationship, but says she had repressed the painful memories of the alleged rape until Roberts reminded her of the Franklin killings. Memory repression is a common response to a traumatic experience, says Candice Lopez, director of the National Sexual Assault Hotline. “But those events come back later when they’re triggered—when something mirrors the event that happened.”

In a statement, Roberts’s lawyers said, “Roberts and Mitchell have stayed in touch over the years, and their contacts have always been warm, caring, and friendly, which makes these new, false allegations all the more puzzling and disappointing.”

Over the next few months, Mitchell says, she became suicidal. She began calling victims-rights organizations but was told there wasn’t much they could do because “it would be my word against his.” She decided she needed proof of their relationship. She drove to a Radio Shack near her home and bought a digital recorder.

On the morning of June 24, 2014, Mitchell waited for the click of the door shutting behind her husband, then hit send on an email to Roberts.

“Silenced memories and fears have been floating to the surface lately,” the message said.

“I asked my mother what I was like after the murders, before we met,” Mitchell continued. “She said that I was very withdrawn and while she was working or even at home, she would constantly call or check to see if I was still alive, still breathing. I was like a silent ghost child with a whisper voice.

“I can see why I was attracted to your energy at the time we became involved.

“I just don’t understand why you were attracted to me. Can you help me understand it?”

The provocation worked. Twenty minutes later, the judge called her from his chambers. She put the phone on speaker, and began recording the conversation.

“I just had to reach out to you,” Roberts tells Mitchell on the recording. “I didn’t want to have a minute pass without you knowing, uh, that I care.”

During the call, Roberts confirms the sexual relationship. Mitchell then tries to clarify its timing: “I remember, you know we talked about it and if anybody ever found out that a mistrial could happen and I, I think that scared me to the core at the time.”

Roberts: “Well. . . remember the timing was, that I was quite insistent in my own mind and perhaps with you, I don’t know if [I] talked to you about it, that nothing happened until after the trial was over so there wouldn’t have been a mistrial. . . .You know we made sure, made sure and in my own professional requirements and responsibilities that that never happened during, before any verdict was rendered.”

Mitchell: “No, remember we were watching it, like we were watching TV and watching the news one day, like right after I had testified, we were, when we were in bed together. . . . Don’t you remember?”

Roberts: “I remember it differently.”

“Oh, I see.”

“Uh, I remember it differently.”

“Okay.”

“. . . . I thought I was very careful about making sure that, uh, uh, you know, your testimony happened and nothing, you know, physical went on until after you had finished your testimony.”

“Oh.”

“Now, maybe that was, maybe what you are saying is that the verdict had not come in but the testimony was all over. Uh, I made sure, I made sure that your testimony, direct and cross-examination and all that was all over.”

• • •

Mitchell brought the recording to the Utah Attorney General, who considered it enough of a bombshell to launch an investigation. Paul Cassell, a retired federal judge retained by the state to review the matter, ultimately determined there was significant evidence that Roberts “did indeed engage in sexual relations” with Mitchell “on multiple occasions” and “under the guise of ‘witness preparation.’ ”

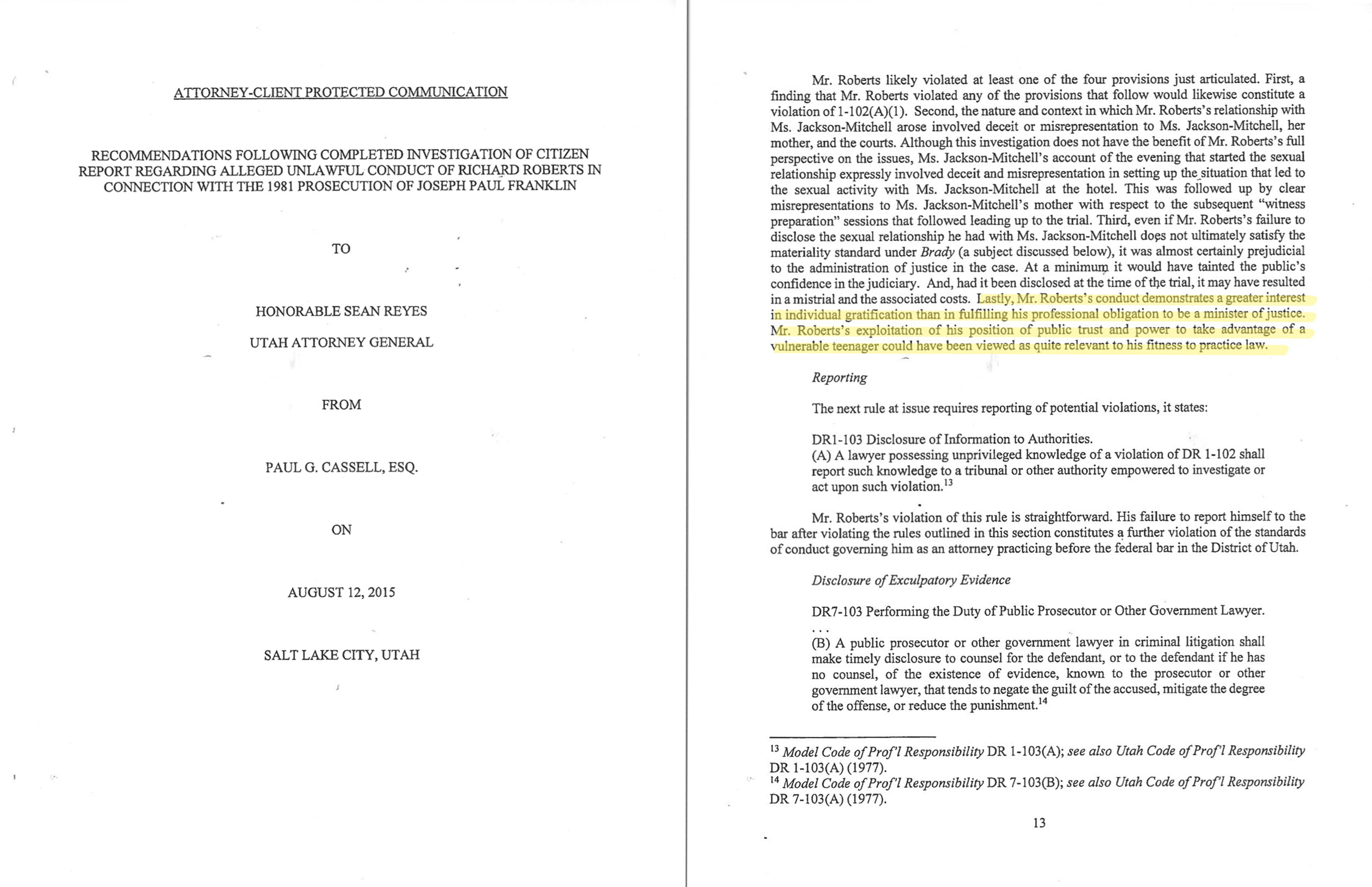

Because the age of 16 was old enough to provide consent at that time, Cassell concluded that the evidence wasn’t “strong enough to support a criminal prosecution” of Roberts. However, Cassell recommended that the Utah AG bring to light the ethical implications of Roberts’s behavior. “Unsurprisingly,” Cassell wrote in his investigative report, “the rules of ethics do not permit a prosecutor in a criminal case to have sexual relations with a witness and then ask her questions during that criminal case. Such actions are fraught with the potential for witness bias.”

Cassell also raised larger questions about Roberts’s judgment, writing: “Mr. Roberts’ conduct demonstrates a greater interest in individual gratification than in fulfilling his professional obligation to be a minister of justice. Mr. Roberts’ exploitation of his position of public trust and power to take advantage of a vulnerable teenager could have been viewed as quite relevant to his fitness to practice law.”

In response, the Utah AG contacted Merrick Garland, chief judge of the DC federal appeals court, to file a misconduct complaint against Roberts. (It’s protocol for a misconduct case against a judge to be handled by the appeals chief above that judge’s trial court.)

Here, the story takes an only-in-Washington twist. Garland, the Supreme Court justice nominee, is an old friend of Roberts; as prosecutors, the two worked on the Marion Barry case together in 1990. Garland recused himself from the misconduct matter. A colleague took over and dismissed the complaint, ruling it was moot, since Roberts retired the same day that news of Mitchell’s allegations broke.

But that wasn’t the end of it. The Utah AG proceeded to petition the full complement of DC judges who oversee misconduct investigations. They in turn kicked the matter up to the US Supreme Court, asking that the complaint get sent to a court outside Washington. Chief Justice John Roberts chose to send the matter to the federal appeals court in Denver for review. A decision is still pending.

• • •

If Ricky Roberts ever worried that his past with Mitchell could resurface, he hid it from Tom Williamson, one of his closest friends. Williamson is a lawyer at Covington & Burling, and Roberts is the godfather of his child. Their families used to vacation together. At no point in their long friendship did Roberts mention Mitchell. In hindsight, says Williamson, “I don’t think [he had] a sense that it was going to come back up.”

Williamson and other friends and colleagues say they were shocked by Mitchell’s lawsuit. Susan King, a retired lawyer who tried civil rights cases alongside Roberts at DOJ, chalks up Roberts’s long-ago interest in Mitchell as a “youthful indiscretion.” She describes how isolating it could be for Washington prosecutors to parachute into other towns: “In addition to having to deal with the stresses of trial, you had to watch your back because the locals didn’t [always] want you there,” she says. “He was young, he wasn’t married, he didn’t have kids, he was under a lot of stress.”

One unanswered question is, would Roberts have acquired as much power as he did if Mitchell’s allegations had come to light sooner? To receive President Clinton’s nomination to the bench, Roberts had to undergo a rigorous review by the White House Counsel’s Office and pass an FBI background check, plus fill out a Senate judiciary questionnaire including the confidential catch-all part that asks nominees to disclose “any unfavorable information.” It’s unclear if the relationship with Mitchell came up; Charles Ruff, then White House Counsel, died in 2000. Mitchell says no one from the vetting team ever contacted her.

What is clear is that the Joseph Paul Franklin case was a game-changer for Roberts. It thrust him into the national media spotlight, impressed DOJ colleagues, and factored into Covington’s decision to hire him, says Williamson, who helped recruit Roberts to the firm in the ‘80s.

When it comes to Roberts’s license to practice law, legal ethics experts I spoke to pointed out that whether Roberts had sex with Mitchell before or after she testified might be beside the point. A DC lawyer doesn’t have to be criminally charged or convicted to be disbarred if there’s “clear and convincing” evidence of wrongdoing. “An [alleged] rape is enough,” says Arthur Burger, chair of the professional responsibility practice at Jackson & Campbell, and a member of the American Bar Association’s ethics committee. (The DC Bar will not confirm whether it is investigating Roberts.)

In his resignation letter to President Barack Obama, Roberts attributed his departure to a health problem rendering him “permanently disabled” from continuing on as a judge. He had to support the claim with a medical report. Colleagues are aware that he’s struggled with some kind of illness but cannot recall precisely what it is. “It’s one of those seven-syllable medical terms,” says Williamson. Of the timing of the judge’s retirement, he adds: “This situation, I think, did tip the scales.”

Because Roberts stepped down for medical reasons, he continues to get his $200,000 salary. He could lose it if the judicial misconduct proceeding doesn’t go his way.

• • •

In April, not long after his retirement, Roberts attended a reception at the Ronald Reagan Building honoring retiring judges. When then-DC Bar president Timothy Webster called Roberts’s name, he took the stage in a silvery gray suit, accepted his framed certificate, and smiled for the photo op. A few weeks later, in May, Roberts was on the scene again, this time at a $300 per head dinner for the Council for Court Excellence. He used to sit on the organization’s board and volunteer with its program teaching DC public high school students about jury service.

Since then, Mitchell has doubled down on her pursuit of Roberts for damages. She voluntarily dismissed her first complaint but filed a new lawsuit in late July. The reason: Utah has a new child sexual abuse law now in effect, which states that anybody who was sexually abused as a minor has 35 years from the time of their 18th birthday to bring a civil case against their abuser. Still, Roberts’s lawyers are arguing that the statutes of limitations have expired.

Mitchell, now 51, says she suffers from PTSD, including insomnia and migraines that last for weeks. Her suit accuses Roberts of assault, battery, intentional and negligent infliction of emotional distress, and false imprisonment (for the times Mitchell says he held her against her will). “Justice would be peace of mind,” Mitchell says, “and I don’t think anything is ever really going to give me that.”

Senior editor Marisa M. Kashino (@marisakashino on Twitter) can be reached at mkashino@washingtonian.com.