Until the Story of the hunt is told by the Lion, the tale of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture opens this weekend and tells the history of African Americans in the United States. As welcome as a national museum to the African American experience is, regional museums throughout the country have held that history together for decades. These museums may not have the budget that NMAAHC does, but their contributions are no less crucial. Here are some ways they’ve documented African American history, and how those compare with the new museum’s approach.

Detroit

The history of slavery is one of the most difficult stories to tell, whether in textbooks, films, or exhibits. The Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History in Detroit was founded in 1965 and expanded over the years to open its largest location in 1997. Until now, it has been the largest museum of African American history in the United States with 125,000 square feet of exhibitions. The most memorable of these is a model slave ship in the center of the long term “And Still We Rise” exhibit which opened in 2004. Through a timeline, it tells this history through multiple media, most notably life-size wax figures to represent different time periods. Forty-three wax figures of men, women, and children, carry visitors through the intolerable conditions enslaved Africans endured on the long and torturous journey across the Atlantic. The story brings viewers on the deck and into the dimmed hull with wax bodies crammed lying down one next to the other on wooden shelves. The experience doesn’t stop at the visual; while walking through, audio overhead plays frightened cries and groans of pain.

While the Wright Museum uses models, the Smithsonian tells its story in part by artifacts. The first part of the museum brings visitors 70 feet underground and tells the story of the slave trade in parts. One of the most notable objects on display is the iron ballast from a wrecked Portuguese slave ship donated by the international Slave Wrecks Project in South Africa. The ship crashed in 1794 after leaving Mozambique, resulting in the death of 223 slaves, the majority of whom drowned. Central objects within this section include a preserved slave cabin from South Carolina, shackles from 1845, and a slave auction block from Hagerstown, Maryland, that once abutted a gas station. Two important religious documents on display are Nat Turner’s bible and Harriet Tubman’s hymnal. The Wright Museum included a wax figure in Tubman’s likeness that speaks to visitors as if she were helping them seek freedom: “I’ll shoot you dead you don’t do like I say. So make up your mind, live North or die here!” The Wright Museum has not yet donated any objects to the Smithsonian, but it plans to work collaboratively as “there’s so much to the black experience that even 100 museums cannot tell it all,” says LaNesha DeBardelaben, Senior Vice President of Education and Exhibitions.

Philadelphia

The permanent exhibit in the African American Museum in Philadelphia is “Audacious Freedom,” essential to the storytelling of the country’s founding from 1776 through reconstruction in 1876. “We wanted to ensure that there was a place that fully represented African Americans’ contribution to the formative years of the country,” says museum president and CEO Patricia Wilson Aden. In this multimedia presentation, there is a Conversation Gallery where visitors can interact with video representations of famous individuals from Philadelphia. One featured figure is Octavius Valentine Catto a 19th-century civil rights activist, intellectual, and teacher who Wilson calls a “renaissance man.” He led protests against Philadelphia’s segregated trolley car system, a fact that “helps children understand that the civil rights movement is centuries old, something that we as African Americans have been addressing across decades,” says Wilson.

At the NMAAHC, the story of segregation and civil rights is again told through important objects and artifacts. One of the oldest objects in the collection that represent segregation are four wooden framed glass windows from the original Antioch Baptist Church in Camden, Alabama. The African American church opened in 1885 and was a source of strength and resilience for the community. One notable guest was Dr. Martin Luther King in 1965 in the height of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s.

New Orleans

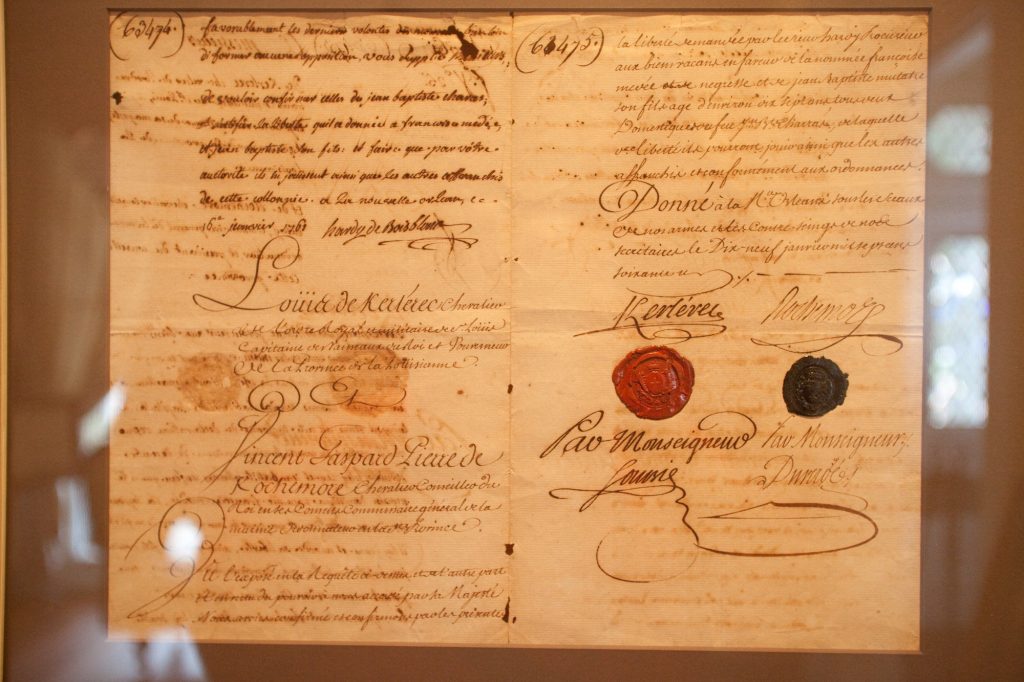

Beverly and Dwight McKenna began collecting art when they were newlyweds, about 40 years ago. They have a pair of museums in New Orleans that share their vast collection with the public: the McKenna Museum of African American Art and Le Musée de f.p.c. Le Musée tells the story of free people of color, often called f.p.c., who were those of African descent free before the Civil War. “We were extensive collectors of the material culture of free people of color,” said Beverly McKenna, founder of Le Musée. The museum contains slave documents and other artifacts to illustrate the lives of free people of color, a large population of whom lived in New Orleans. In the McKenna Museum, one gallery focuses on music in “Our Music Is Our Culture,” featuring Leroy Campbell’s mixed-media piece “Second Line.”

While the NMAAHC might not have a similar representation of the specific culture of free people of color, music plays a big role in its “Community and Culture” section. The museum actually houses New Orleans native Louis Armstrong’s trumpet honoring the jazz musician’s amazing contributions through music. If visitors have a hankering to dance, the “Musical Crossroads” gallery features famous performances by Marian Anderson or Jimi Hendrix.

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Like many founders of African American Museums throughout the nation, Sadie Roberts-Joseph, founder and chief curator of the Odell S. Williams Now And Then African-American History Museum in Baton Rouge, believes that regional museums often play an important role in the communities in which their housed. “African American history is definitely the history of America and it is important for all to be aware of the many contributions that African Americans have made to the growth of our nation.”

Created in 2001, the museum is based off a collection of photographs by the late Odell S. Williams, a former school teacher in the Baton Rouge area. Williams use to hide the photographs under her desk due to it being illegal to teach what was not in the textbooks during the 1950s, says Roberts-Joseph. By contrast, the National Museum of African American History and Culture’s exhibits on events such as the Civil War include more tangible artifacts such as military identification tags, a 1853 rifle, photographs, and recruitment advertisements. The Louisiana museum’s collection is mainly a visual one that includes photographs of prominent change-makers, single representative items such as a statue of a black soldier to represent the 1st Louisiana Native Guard and all black regimen of free people of color as well, as the 186,000 free blacks who fought during the civil war, and an outdoor Historic Walking Trail which utilizes concrete Interstate support columns to provide visitors a physical representation of the number of African Americans who were enslaved and free in all 11 states that succeeded from the Union.

In addition to its focus on the Civil War, the museum also looks to tell the story of the Civil Rights Movement. It does so through the use of a 1953 city bus that was part of the Baton Rouge bus boycott; the first African American bus boycott in America.“It was only one week but it was a beginning of a movement,” says Roberts-Joseph. In 1955, Dr. King visited the city and met with leaders of the boycott to learn from their resistance. The NMAAHC has a much larger and more comprehensive civil rights exhibit that includes a segregated trolley car from Southern Railway, ticket stubs, pamphlets from Dr. King’s Funeral Service, and an FBI wanted poster for Angela Davis.

Chicago

Beginning as the Ebony Museum of Negro History and Art and housing over 15,000 pieces, the DuSable Museum of African American History in Chicago was founded in 1961 by Dr. Margaret Burroughs and is the oldest independent African American Museum in the Nation. Burroughs, who assisted Dr. Charles H. Wright in establishing the Wright Museum in Detroit, wanted the museum to be a place to study and preserve African American art, history, and culture. As such, many of the museum’s exhibits center on the past but also more contemporary issues and artistic mediums. In fact one of its newest exhibits, Drapetomanía, highlights the work of Cuban visual arts group Grupo Antillano (1978-1983), which focused solely on the African and Afro-Caribbean influences that affected the founding of the Cuban nation. Leslie Guy, chief curator of the Dusable, says the traveling exhibit is unique because it depicts the ways one can connect to others of the African Diaspora. “It’s really important to realize that we’re a large country and the black experience is diverse. It’s just a diverse as the American experience. No one would ever say we’re going to have a single museum of American history. No one place can talk about the entire African American experience.”

While the NMAAHC also utilizes mediums such as paintings in its exhibits of the diaspora, what makes the Dusable stand out is its singular presentation of the Afro-Cuban experience. The NMAAHC, on the other hand, looks to encompass and narrate the black experience from various regions, perspectives, and angles; incorporating everything from pins and photographs to sculptures and jewelry from places all over the world.

Honolulu

Something to look out for in the future is the African American Diversity Cultural Center Hawaii (AADCCH), which is in its collection phase. Relying on histories collected from resident interviews, the center focuses on untold stories of early settlers of African descent on the islands.

While the NMAAHC helps to highlight the overall black experience in America, the contributions of regional museums to the national storytelling effort of African American history cannot be understated.“Museums are more than just about objects, museums are gathering places,” says the Wright Museum’s DeBardelaben. These smaller museums may not gain the same audience as the Smithsonian, but visitors to them will have beautifully different experiences.