The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture is not a one-day museum. Unlike its peer institutions along the Mall, which whether by ubiquity or scope of the collection can be consumed in a single visit, this new museum packs in so much history—more than 600 years, in fact—it’ll take a few trips to take in the entire presentation.

But if you only have a day, these are 11 things worth stopping at.

The museum’s below-ground floors of exhibit space tell the long, raw, and often brutal story of the black experience in America, beginning with the origins of the Atlantic slave trade in the late 15th century. On display are some of the glass beads, metal bands, and rifles European colonialists used as currency to trade with African leaders for human flesh. A display describing the slave-trading practices of five European nations spells out the carnage even more. The wall is printed with records of slave ships’ trans-Atlantic journeys, including their dates of travel and how many slaves on board perished during the trips—the body counts are staggeringly high. In another room, the Smithsonian is displaying wreckage from a Portuguese ship that sank off the coast of South Africa in 1794, killing more than half the estimated 400 slaves on board.

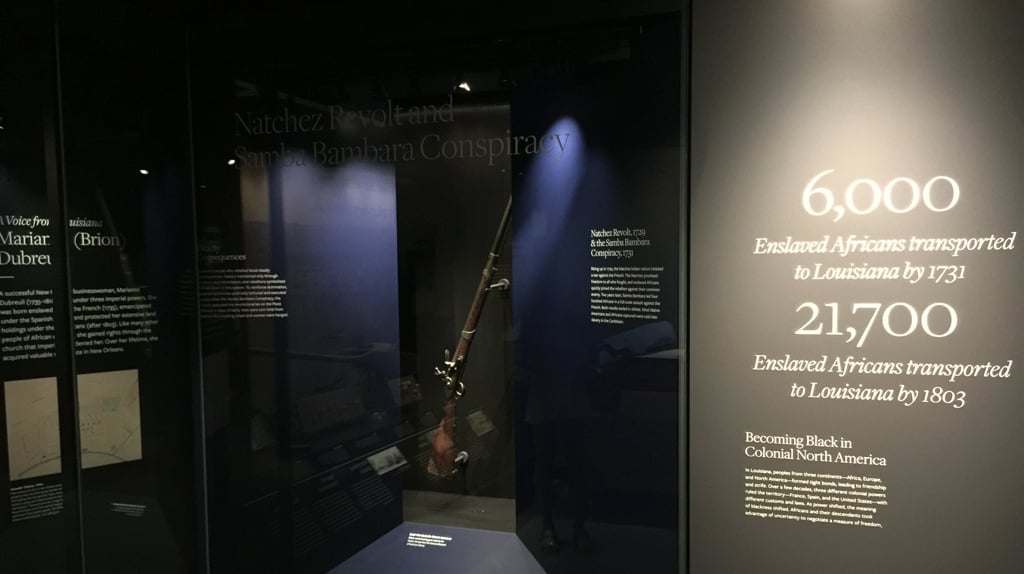

Windows into slavery practices in various regions of the colonial and post-revolutionary United States amplify the domestic toll, but there’s a twist: each one ends with an artifact from an act of resistance—a case about Louisiana concludes with a rifle used in 1729, when several hundred slaves joined a Natchez Indian rebellion against French colonizers.

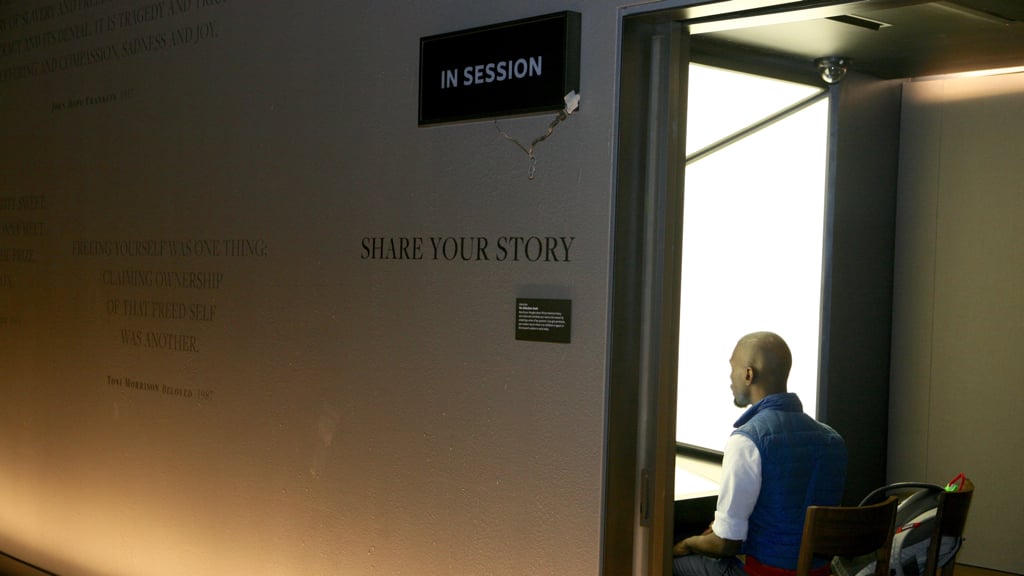

Spread throughout the museum are recording booths where visitors can share their own stories for the Smithsonian to collect and display online and in future exhibits. DeRay McKesson, a Baltimore school administrator and one of the most prominent exponents of the Black Lives Matter movement, paused his visit to record something. McKesson’s own experience shows up at the tail end of the chronological tour, with quotes from his fellow Black Lives Matter organizers included in a display about present-day activism. “We didn’t invent resistance,” he said. “The current movement is just an iteration. Hopefully there will be a day we don’t have to document trauma.”

Activism and resistance is also on full display at an interactive table lined by the stools from the lunch counter at the Woolworth store in Greensboro, North Carolina, the site of many sit-in protests against racial segregation. The displays inside the table ask visitors what they would do if they were present at different chapters in the history of the Civil Rights movement.

Hanging from the ceiling, and polished to look brand-new, is a training airplane used by the Tuskegee Airmen in World War II. The plane, which had been wrecked in a crash, was purchased in 2005 by a retired Air Force captain who repaired it, and later donated it to the Smithsonian.

The chronological tour finishes with artifacts and videos from President Obama‘s first election and time in office. It’s laid out like an exclamation point, but the cavernous exhibit hall seems to have room for more history.

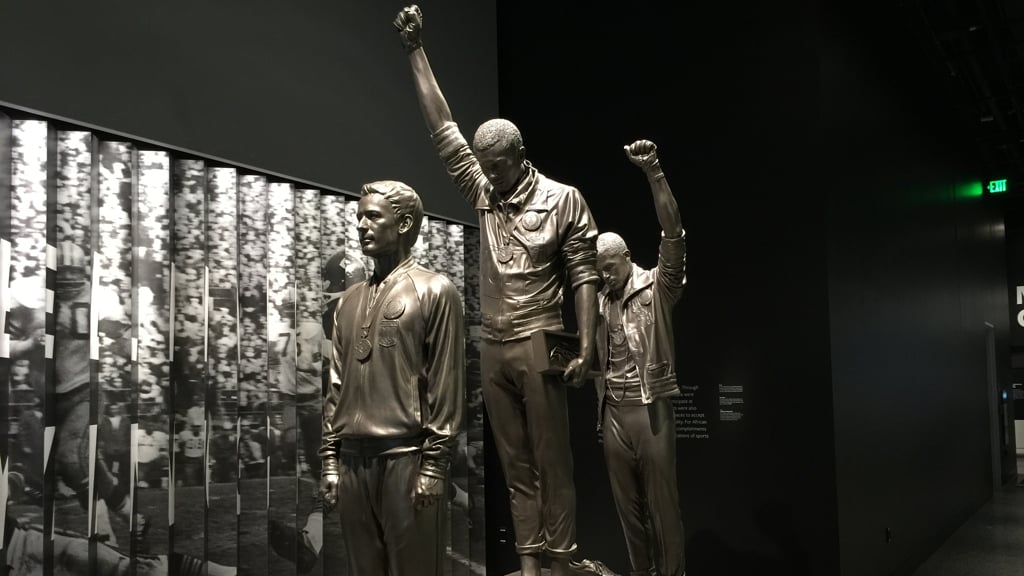

The above-ground floors are filled with exhibits documenting African-American communities and black contributions to all aspects of American culture, including education, business, visual and performing arts, and sports. The extensive sports exhibit on the third floor is dotted with statues of Jackie Robinson sliding into home plate, Michael Jordan hitting a fadeaway jump shot, Serena and Venus Williams in a doubles match, and John Carlos, Tommie Smith, and Australian runner Peter Norman’s protest at the 1968 Summer Olympics.

Around the corner from the sports displays is the “Place Table,” a large, interactive surface showing dozens of professional and personal photographs dating back more than a century. Behind each photo is a story—taken from either previously published works or memories the Smithsonian collected from people who donated the images—that describes African-American life in every pocket of the country. “We wanted to do an exhibit about regional African-American culture,” Paul Gardullo, the curator overseeing the exhibit, said. “‘Place’ is also about displacement.”

The fourth-floor is all about arts and culture. An exhibit about fashion includes not only the black designers who have shaped what Americans wear, but also the clothing worn by some of the most significant moments in history, including the dress worn by Rosa Parks when she was arrested in 1955 for not moving to the back of a city bus in Montgomery, Alabama.

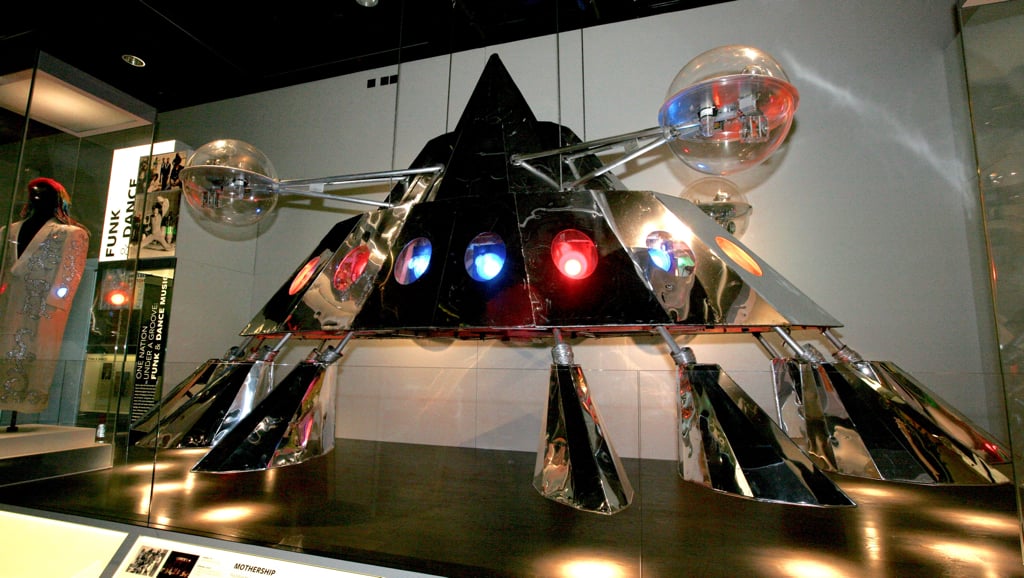

The top floor’s largest space is all about music, from early folk songs to modern hits. There are plenty of items from the figures one expects—B.B. King, Prince, Public Enemy, the Jackson family—but also artifacts from musicians outside the mainstream, like a lime-green suit worn by members of the Dixie Hummingbirds, an influential gospel group whose surviving members will perform during the weekend-long music festival marking the museum’s opening.

Looming largest in the music display, though, are Chuck Berry‘s cherry-red 1973 Cadillac El Dorado convertible, and the Mothership, the otherworldly spacecraft George Clinton sometimes emerged from at the start of a Parliament Funkadelic show.

These are just a few slices of the museum, which may be the Smithsonian’s best in terms of detail, narrative, and historical scope, but also its most challenging. It’s a collection devoted to recounting the country’s history, with some of its biggest warts on full display, and also celebrating some of its richest culture. It’s no wonder, then, that passes to visit in the first few months after the September 24 opening are in short supply. Here’s how to get tickets.