Zachary Hudson has succeeded if you never notice what he does for a living. As an exhibit specialist for the Smithsonian Institution Exhibits, the 25-year-old is responsible for transporting hundreds of historical objects from behind closed doors to carefully constructed, temperature-controlled displays. He is also responsible for making sure those displays do as little as possible to detract from the powerful objects that they hold.

Hudson did not plan to enter this line of work. While studying for a philosophy degree at New College of Florida, he began lending a hand at the John and Mable Ringling Museum near the school. Around the same time, he began assisting freelance artists and sculptors as well–because of the state’s climate, arts funding, and lack of income tax, South Florida makes particularly fertile ground for large-scale sculptors. The physical work was a relief from his intellectual studies, and handling artifacts with respect came naturally. Eventually his passion for his work overtook his studies.

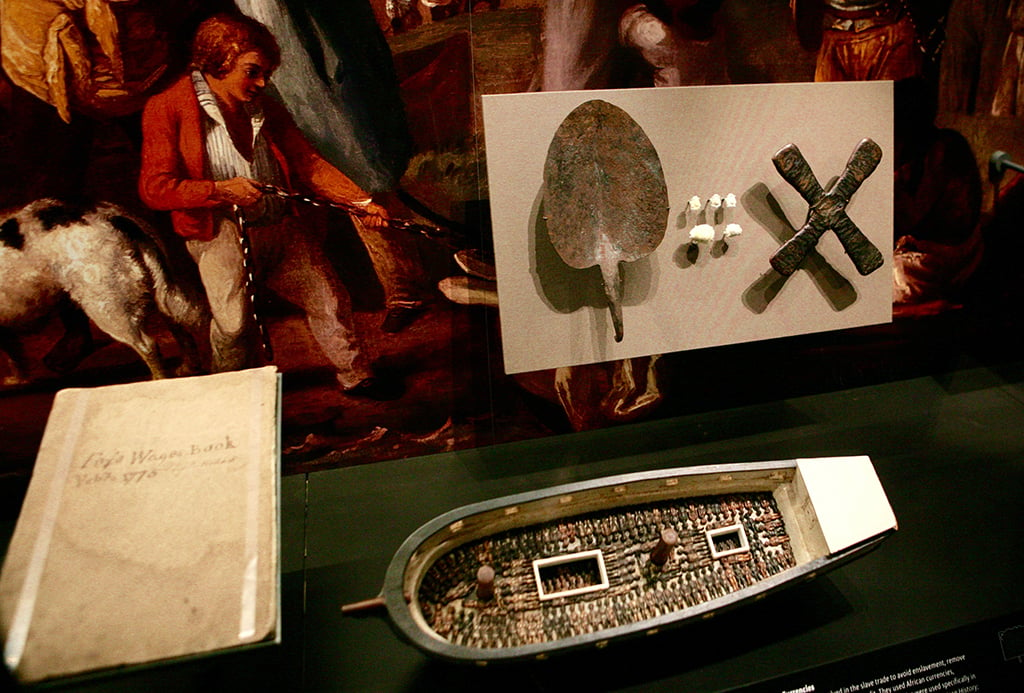

Hudson moved to DC in May 2015 to participate in the construction and display of some 3,000 three-dimensional objects in the 322,600-square-foot National Museum of African American History and Culture, working as one in a team of dozens of individuals responsible for displaying the artifacts.

The process has been thoroughly enjoyable, he says, even when approaching a particularly difficult object in this project, such as the already popular exhibit of Chuck Berry’s 1973 Cadillac El Dorado convertible. “They wanted it in the music gallery, on the top exhibit floor–this giant boat-size cherry red Cadillac–and they wanted it hanging several feet in the air compound angle.” In order to make it happen, the unit had to disassemble major machinery, carry it in, and rebuild it inside the museum. The hanging took nearly 12 hours. “To get that car and angle without screwing it up was a huge problem,” Hudson explains, “But that is a cool object. Berry’s caddy, man.”

The environments Hudson creates are referred to as “exhibit furniture” or “exhibit cabinetry.” He may broadly be referred to as an exhibit specialist, but he also has a specialization within his specialization: Hudson focuses on mount-making, the highly specific and often painfully detailed build-outs used to prop up and hold various museum artifacts. He describes himself as having a somewhat minimalist approach to his work in that, on average, he will only utilize 30-50 tools to build each mount. Some exhibit specialists have tools that number in the hundreds, ranging from technical pliers to Brillo pads, latex gloves, and minuscule jewelers tools. Hudson was one of several such specialized mount-makers working on the National Museum of African American History and Culture project.

Each exhibit incorporates input from dozens of specialists–electricians and designers, directors, architects, graphics developers, historians, historic preservationists, and yes, mount-makers. Hudson and each of his fellow mount-makers receives a briefing on the vision for each and every object’s display that comes from exhibit designers and takes into the technical aspects of the exhibit in the form of a printed packet, which distills down all pertinent information. There is a lot to consider: Is the object fragile? Can it handle being touched more than once or twice? At what height should it be displayed? What features do the historians want highlighted visually? How can the lighting be set up to have the most impact? At what temperature and humidity should the case be set to ensure the artifacts longevity? From there, the vision is in his Hudson’s hands. It is his duty to make the theoretical happen.

Hudson starts by going to where the object is kept in storage. If possible, he will delicately lift the artifact in question to evaluate its balance point. He mentally sketches out how the item will be displayed with the most minimal materials possible, whether that means hanging it by near-invisible wire or using a discreet pedestal hidden by the object’s girth. Precious jewelry, paper-thin tickets, dresses, vintage marionette dolls, rust-eaten weapons–Hudson has handled them all.

Next he sketches out a shape and begins a rough-in. Once he has built up a shape he visually checks it next to the object in order to make sure the strategy still makes sense. Then, his work begins in earnest, padding a skeleton of plastic, brass, or other metal with materials that are safe to come into contact with the item (for example, certain types of modern paper products can cause silver to tarnish when housed in the same display case). Next he paints it to be camouflaged, makes sure that complications have been addressed before finalizing the ‘furniture,’ and then packs it away in an organized manner so that when the time comes to install the display, the furniture is ready and waiting. Depending on the three-dimensional object being displayed, the entire process can take a few hours to several days.

“Everyone on the team knows building trust with the people that own the collection is so important,” explains Hudson. “A lot of times the value is just impossible to put a number on. Something like a old movie ticket, we know that just because the historical value isn’t obvious to us as mount-makers doesn’t mean anything. We treat it with as much respect as if we did know.” That respect is as essential to his work as his technical skill. Communication between the museum’s historians and preservationists is of the utmost importance if the objects are to reach their final resting cases intact and in as pristine condition as possible.

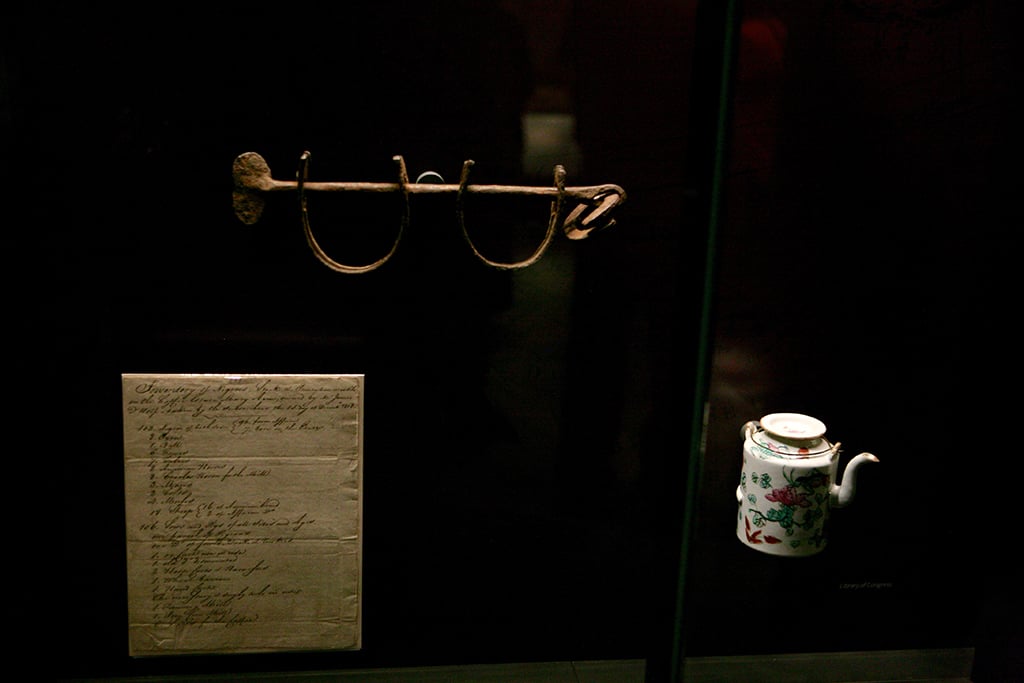

Though Hudson has worked on various museum collections throughout the years, he describes the past 17 months working on the National Museum of African American History and Culture’s opening as fundamentally challenging. “It’s not the first time I’ve worked with objects that had a troubling or problematic history,” he explains, “But just the scope and quantity of what we’ve been working with…it’s a pretty emotional concept. So much time with these particular artifacts has had a pretty heavy impact that I wasn’t expecting. An impact that goes beyond the normal work pressures of a big opening.”

“Everything this old has a smell. Because they are kept in cases, the visitors to the museum are shielded from that. They might stand in front of an exhibit of a 19th-century slave whip and read the explanation of the history and be nauseated,” Hudson explains, “But when you touch it and you feel just how heavy it is. When you feel that it’s been seasoned by blood and oils, when you can smell a human smell on it. That’s a lot to process. It has a psychological dimension that is difficult to capture.”

“For better or worse,” Hudson says, “visitors don’t experience that.”