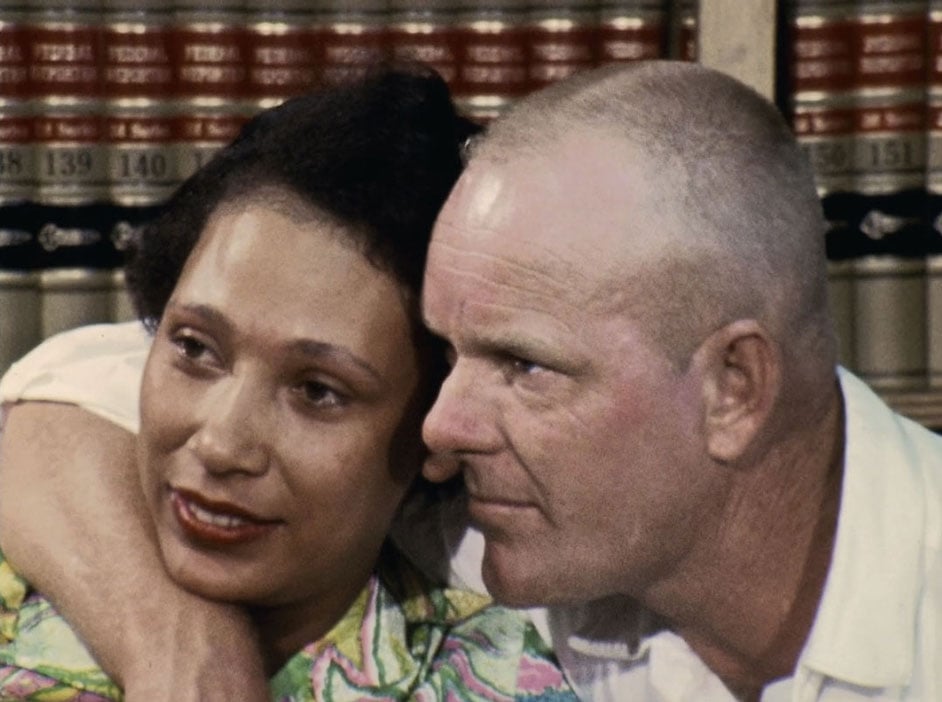

In June 1958, Mildred Jeter and Richard Loving drove from their home in Central Point, Virginia, to Washington, DC, to be married. Twenty-four states, including Virginia, still outlawed interracial marriage at the time. Mildred was part Native American and part African-American; Richard was white. Their union would eventually result in their banishment from the state and a nine-year legal battle.

On November 4, almost 50 years after the Supreme Court’s 1967 decision that the Lovings’ marriage was valid—and that marriage is a universal right—Hollywood is set to release Loving, already on Oscar lists. As director Jeff Nichols explained when asked why he took on the project, “We have very painful wounds in this country, and they need to be brought out into the light. And it’s gonna be an awkward, uncomfortable, painful conversation that’s going to continue for a while.”

The movie focuses on Mildred and Richard’s romance. We looked behind the scenes of the struggle itself, talking to insiders including the couple’s attorneys—then just out of law school—to revisit the case. One remarkable aspect: Unlike other civil-rights champions of their era, the Lovings never set out to change the course of history. “What happened, we really didn’t intend for it to happen,” Mildred said in 1992. “What we wanted, we wanted to come home.”

This is the story of how a quiet couple from rural Virginia brought about marriage equality for themselves, and for all.

Mildred Loving, in archival film footage from the mid-1960s: “We were married on the second day of June, and the police came after us the 14th of July.”

Richard Loving, in the same footage: “They knocked a couple times. I heard ’em, and before I could get up, you know, they just broke the door and came right on in.”

Mildred: “It was about 2 am, and I saw this light, you know, and I woke up. There was the policeman standing beside the bed. And he told us to get up, that we were under arrest. . . . They asked Richard who was that woman he was sleeping with, and I said, ‘I’m his wife,’ and the sheriff said, ‘Not here you’re not.’ ”

Author Peter Wallenstein in his book Race, Sex, and the Freedom to Marry: “Mildred was not quite nineteen years old, at least five months pregnant, and the mother of a young child.”

Phil Hirschkop, the Lovings’ Washington attorney: “She was held in jail for the better part of a month. It was a filthy little tiny black cell with a metal bunk.”

Deputy Sheriff Ken Edwards, in the archival footage: “That jail was hell. It had 16 bunks in it, but it wasn’t no motel.”*

*Wallenstein describes the jail this way: “The building was described ‘inadequate,’ and the ‘plumbing in the room on the second floor used for segregation of females or juveniles’ as not only ‘obsolete’ but also ‘entirely out of order.'”

Richard was jailed for only one night but wasn’t allowed to bail out Mildred. By the time of their arrest, the Lovings had been in a relationship for many years.

Wallenstein: “As early as 1950, Richard Loving, at about the age of 17, began stopping by the home of friends of his, where he made the acquaintance of their 11-year-old sister, Mildred . . . . [T]hey developed a friendship, and eventually they began courting.”

Nancy Buirski, director of the 2011 HBO documentary The Loving Story: “It’s a small town—it wasn’t unusual for blacks and whites and Native Americans to socialize, because they were living together in a small environment. Apparently, Mildred’s brothers played hillbilly music and people would come to their house and listen to it, and I think that’s the story—that Richard would come and listen.”

Mildred: “People had been mixing all the time, so I didn’t know any different.”

Buirski: “I’m almost sure Richard worked in a lumber mill. For a period of time, he worked for either Mildred’s father or someone in Mildred’s family—it was interesting that he was working for a black man.”

Jeff Nichols, director of Loving: “The road that passes through Central Point is called Passing Road, and passing for white was a thing that happened quite often in that community. I think Central Point’s an outlier; I don’t think it’s typical of that period.”

Wallenstein: “On January 27, 1957, [Mildred and Richard] had a son, Sidney. The midwife was Richard Loving’s mother, Lola Jane Loving, who delivered most of the children in the area . . . . Mildred continued to live at home unmarried with her parents, and that’s where Sidney lived, too.”

Virginia’s 1924 Racial Integrity Act criminalized all marriages between “white” people and those who were “colored”—meaning anyone “with a drop of non-white blood.”

Mildred: “I didn’t know there was a law against it. You know, the white and colored went to school different. Things like that. . . . But I didn’t realize how bad it was until we got married.”

Nichols: “Her getting married wasn’t an act of protest. It wasn’t a symbol for anything other than her love for Richard. I do think he knew nobody would marry them around Central Point—and so he took her up to DC.”

Wallenstein: “They made a first trip north on May 24, a Saturday, to apply for a marriage license. On Monday, June 2, they went back. . . . Reverend [John] Henry conducted the ceremony at his place at 748 Princeton Place, Northwest.”

The Lovings lived together in Central Point for about six weeks before their arrest.

Bernard Cohen, the Lovings’ Washington attorney: “Mr. Loving speculated that there was some jealousy among some of the white men who were speed-car racers—that was a major part of the entertainment that Mr. Loving and others engaged in. They hardly ever lost. There was a feeling that perhaps there was some jealousy and they got turned in—but he didn’t know for sure.”

The Lovings’ son Donald was born in early October 1958. Shortly afterward, the couple was indicted and convicted.

Wallenstein: “Judge [Leon] Bazile pronounced the sentence, ‘one year each in jail.’ But he promptly suspended the sentence, ‘for a period of twenty-five years,’ provided Mildred and Richard both ‘leave Caroline County and the state of Virginia at once and do not return together or at the same time during that twenty-five years.”

Wallenstein: “Mildred had a cousin living in DC. . . . They lived at 1151 Neal Street, Northeast, in a black part of town [Trinidad], and that is where the Lovings—Richard, Mildred, Sidney, and Donald—took up residence.”

Nichols: “They just had to go to DC—what’s the big deal? An hour and a half away—they didn’t even have traffic back then. Like, come on, they’re not being thrown in prison. But it is a big deal.”

Mildred: “I didn’t want to, you know, leave away from ’round my family and my friends. . . . When I was in Washington, well, I just wanted to go back home.”

Nichols: “You might find another person who thought DC in the ’60s in that neighborhood was awesome, but that wasn’t Mildred. She thought it was a prison. And she speaks to it: ‘It’s like [my children are] caged.’ ”

Five years into the ordeal, the Lovings had had enough.

Mildred: “My older son came back and told me that Donald had been hit by a car. . . . I knew I had to go to him, but I didn’t know if he were dead or . . . . He was sitting up in the street crying. And I think that was the straw that broke the camel’s back. I had to get out of there.”

Hirschkop: “You had the Kennedy assassination, you had the four girls bombed at the church in Alabama, you had a major civil-rights leader killed in Mississippi—it was a horrible summer. And then ’64 comes along and you have the fight over the passage of the Civil Rights bill.”

Mildred: “I wasn’t in anything concerned with civil rights. I was trying to get back to Virginia. . . . I was so unhappy, I was complaining to my cousin constantly. So one Saturday I guess she got tired of it [and] she told me, ‘Write to Bobby Kennedy. He’ll help you. That’s what he’s up there for.’ ”

She sent a letter to Kennedy, the US attorney general, and had a reply within a month.

Wallenstein: “One can imagine her delight and anticipation as she opened the envelope, and then her concern and uncertainty as she digested its brief contents: Kennedy could not help directly, but perhaps something could be done. She should inquire of the American Civil Liberties Union.”

Cohen: “I was a volunteer attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union. The first contact with the Lovings was a phone conversation that lasted three to four minutes. We made an appointment for them to see me in Washington. Mr. Loving was a very quiet, almost shy, introspective person. He let his wife do most of the talking.”

Nick Kroll, who plays Cohen in Loving: “A big-city Jewish lawyer is not gonna be a guy Richard Loving is gonna immediately connect with.”*

*Nick Kroll on his numerous ties to the Loving case: “Weirdly, my father went to Georgetown Law school almost exactly when Bernie was going there to talk to [Chet]. And my dad actually worked for Robert Kennedy while he was in school: he worked at RFK’s office and then actually ran his campaign in Queens when he was running for president. And I went to Georgetown. So I had a number of weird connections to the whole thing, including the fact that I’ve played a defense lawyer before, a very different kind of defense lawyer, in that Ruxin [Kroll’s character on FX’s The League] represented the worst people in the world.”

Cohen: “On November 6, 1963, I filed a motion to vacate the judgment and set aside the sentence. Judge Bazile took it under advisement but did not rule in the case. So the motion just was there, sitting in the courthouse.”

Hirschkop: “Bernie had heard nothing.”

Cohen: “Many months went by without our contacting the Lovings, explaining to them that we were doing deep research but not having very much success.”

President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 on July 2 of that year.

Hirschkop: “Three or four days later, Mildred writes to Cohen and says, ‘Do you remember us? We’re the Lovings. We had given up hope. We thought you forgot about us.’ He gets that letter, and he must be thinking, ‘Gee, I’ll get sued for malpractice.’”

“My constitutional-law professor, who’d got me into civil rights, was Chester Antieau. I was visiting with him in the lounge [at Georgetown Law]. A woman brought a note in and said a young student of his wanted to see him about a case. Bernie Cohen was brought in.”

Wallenstein: “The two young lawyers, both from Jewish families, had both grown up not far from Manhattan . . . . Both had attended college in New York City . . . . Both had made their way to the nation’s capital, working for the US government, and both had also attended Georgetown University’s evening law program.”

Cohen: “I was an old man of 29.”

Hirschkop: “I was close to 30. My desk was half the size of this table. I sat on [one] side, and [legal assistant] Joe Goldberg sat on [the opposite] side. If I slid my chair back, I hit the wall. If he slid his chair back, he hit the wall. It was an oversize desk/closet.”

Cohen: “When we first got the case, we thought it was hopeless because so many years had passed since they pleaded guilty.”

Hirschkop: “My early research showed that Cohen had opened up a huge trap without realizing it. If the state set aside the sentence, the Lovings would be resentenced. It’s a good chance they would have got three to five years. The state would take the position that they waived their constitutional rights by pleading guilty.”

Hirschkop decided they had to get the matter into federal court.

Hirschkop: “[After my meeting with Bernie,] I flew to Mississippi, and on the plane I pulled out a yellow pad and sketched an outline of a federal complaint.”

Cohen: “On October 28, 1964, Phil and I filed in the Eastern District of Virginia, requesting a three-judge federal court be convened to declare the section of the Virginia code unconstitutional.”*

*Explains Hirschkop: “The school of thought in those days among civil rights lawyers was to affirmatively pursue your remedies in Federal Court. The federal judges were far better than the State judges: you try to stay away from judges appointed by President Kennedy, he was horrible at appointing judges. I remember him appointing one guy to the Federal bench who had to take the bar five times, I mean it was My Cousin Vinnie being put on the federal bench.”

Wallenstein: “Where the ACLU emphasized the Fourteenth Amendment [ensuring equal protection and fair treatment] as interpreted in Brown v. Board of Education and in McLaughlin v. Florida [which overturned a law barring cohabitation by mixed-race couples], the state of Virginia emphasized . . . that states had authority over the regulation of marriage. One side emphasized how far the Fourteenth Amendment could reach, the other the limited intent of its framers.”

Hirschkop: “We have what’s called the ‘rocket docket’ in the Eastern District. It’s the shortest docket in the country. These judges give you like three, four months, to take depositions, prepare, go to trial—it’s crazy. I did my homework on the Commonwealth’s possible defenses. The lead defense was that a mixed marriage would have a horrible impact on the children.”

On January 27, 1965, the Lovings’ lawyers argued their case in Richmond.

Cohen: “Three judges took the matter under advisement and then ruled that Judge Bazile should be given the opportunity to rule on my still-pending motion to vacate the judgment. They let him know in no uncertain terms they wanted a ruling. Bazile affirmed the Lovings’ convictions.”

Bazile, in his opinion: “Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay and red, and he placed them on separate continents. And but for the interference with his arrangement there would be no cause for such marriages. The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix.”

Buirski: “The Lovings weren’t the kind of people who drew attention to themselves. We’re living in a society where everybody wants to be a celebrity, wants credit and attention. They were just the opposite.”

Kroll: “I said more in [one] scene than Richard says throughout the entire movie.”

Nichols: “There’s this great moment [in the archival footage] where the interviewer is asking them to explain the arrest. They’ve done this a million times now, and she says, ‘You say it,’ and he goes, ‘No, no, you say it.’ He really didn’t want to talk. It’s a perfect married-couple moment.”

As their case moved through the courts, the Lovings secretly moved back to Virginia.

Cohen: “They didn’t even take me into their confidence at first to tell me they were sneaking back. But they got caught and arrested again. We talked our way out of a prosecution.”

Hirschkop: “I got on a conference call with [prosecutor Robert] McIlwaine and Judge [John] Butzner, and they agreed they would not prosecute the Lovings no matter where they were living.

“[It wasn’t] a normal attorney/client relation with the Lovings. I met them a couple times, but I never had a detailed conversation about their background, their life, their damages. Never met their parents. Never met their sisters or brothers. Or friends.”

Wallenstein: “Now they could legally return to Virginia—or actually, stay in Virginia.

Cohen: “We filed a notice of appeal of Judge Bazile’s decision. On March 7, 1966, the Virginia Supreme Court affirmed the Lovings’ conviction.”

Hirschkop: “They said Plessy [the 1896 case that upheld racial segregation in public facilities] is still good law and that Pace [the 1883 decision that upheld Alabama’s anti-miscegenation law] is still good law. It was an outrageous decision.”

Hirschkop: “Instead, I go to the Virginia Supreme Court and say, ‘We want the option to appeal to the US Supreme Court.’

“They’re faced with—if they say no, they really look like racist pigs.”

Cohen: “It went right to the Supreme Court.”*

*As Wallenstein explains: “The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 were both on the books, [Cohen and Hirschkop] noted, so ‘the elaborate structure of segregation has been virtually obliterated with the exception of the miscegenation laws.'”

Hirschkop: “What would have happened if the state offered a deal to the Lovings? The Lovings were not civil-rights people. They didn’t get in this to make a point, only to go home. What if they came to the Lovings and said, ‘You drop your lawsuit, we’ll guarantee no criminal prosecution. You can go home—you just can’t live as a married couple’? I don’t know they wouldn’t have taken that.”

Buirski: “I think they began to understand the significance of what they were doing.”*

*Buirski: “The Lovings were mostly reluctant to do publicity, and they had gone for many years without doing any publicity. But in 1965 when the case was beginning to gather momentum, Bernie Cohen encouraged them to allow [documentarian] Hope Ryan to come and visit them because he felt it would help the case. … I think by then, they realized they were doing something that was not just for them, but for many more people like them.”

Cohen: “When I first met the Lovings, I expressed the opinion that this was a major civil-rights case that would end up before the Supreme Court. Mr. Loving’s jaw dropped.”

Hirschkop: “No one thought that at the beginning. They take one out of thousands. And they have strict guidelines of what type of case they review.”

In December 1966, the court took the case.

Hirschkop: “About that time, Mel Wulf [legal director of the ACLU] surfaced again and said, ‘Bill Zabel is going to write the brief.’ I was like, who the f— is Bill Zabel? I talked to Bernie, and we were disturbed. A, the Lovings were entitled to pick out their lawyers; we just couldn’t impose it on them. B, we had done all this work, and I felt fully capable of arguing in the Supreme Court. I talked to Mel, and the communication basically was that I would consult with Bill Zabel.”

Cohen: “We were naive enough not to be daunted. We were utterly confident beyond any right to be so.”

Wallenstein: “The ACLU lawyers argued, of course, that Virginia’s miscegenation laws could not pass constitutional muster. Phil Hirschkop focused on the equal protection clause, Bernard Cohen on the due process clause [the legal obligation of all states not to unfairly deprive any citizen of ‘life, liberty, or property’].”

Hirschkop: “We just threw in the kitchen sink. We briefed both.”

On April 10, 1967, the Supreme Court held oral arguments.

Hirschkop: “I wasn’t nervous. I was kind of looking forward to it. I had done so much in the case, dug so deeply, I knew every fact, I knew every state law.

“But first, it’s a little confusing: You’re not sure where to sign in—it’s a big building—[or] where your coat goes. Say goodbye to Mom and Dad, just go get in that line. And you get a quill the first time—a pen quill.

“I argued first, very few questions. Just questions of intellectual interest. But no one challenged me on a point of law.”

Wallenstein: “The Tenth Amendment [which upholds states’ rights], Virginia argued, and not the Fourteenth ought to govern marriage.”

Hirschkop: “[Virginia assistant attorney general] McIlwaine got up, and that was a roast. They kept him up there twice the allotted time, which is very extraordinary. I remember Chief Justice Earl Warren asked him what was the basis of their position. He said there had been studies about the effect of mixed marriages on children, and [Warren] said, ‘What studies?’ [McIlwaine continued,] ‘Well, there have been a number of studies, and it’s a slippery slope if you allow this. . . .’

The chief justice said, ‘Isn’t that the exact same argument made in Brown v. Board of Education, that if black children were allowed in schools, all sorts of terrible things would happen, and it was that slippery slope, and that never happened, either?’”

Wallenstein: “Warren was skeptical; for the past 12 years a daughter of his, raised a Protestant, had been married to a Jewish man, and he interrupted McIlwaine: ‘There are those who have the same feeling about interreligious marriages.’ ”

Hirschkop: “I could have sent Bob Marley to bargain with the Supreme Court that day and it would have had the same result.”

You can listen to the complete oral arguments of Loving v. Virginia here.

Cohen: “There was some speculation that the verdict would be unanimous. There’s months of fun discussion to be had about the case while the decisions are pending.”

Hirschkop: “The questions really signaled where they were gonna go. And unless there was some huge screwup, that’s the way it was going. In Loving, the only thing to really question was: Had it reached its time to take up something that sociologically sensitive?”

Buirski: “Initially, the vote wasn’t unanimous, but Earl Warren felt very strongly about not passing the ruling out to the public until he had a unanimous vote. He felt that this would be a game-changer, probably a political powder keg, and that the argument could be made more strongly in favor of it, politically and culturally, if the court had been unanimous.”

Hirschkop: “[The Lovings] could have come to the Supreme Court. They absolutely didn’t want to. They didn’t want the press. They weren’t even curious—they just wanted a good outcome. There was only one hearing that the Lovings ever attended.”

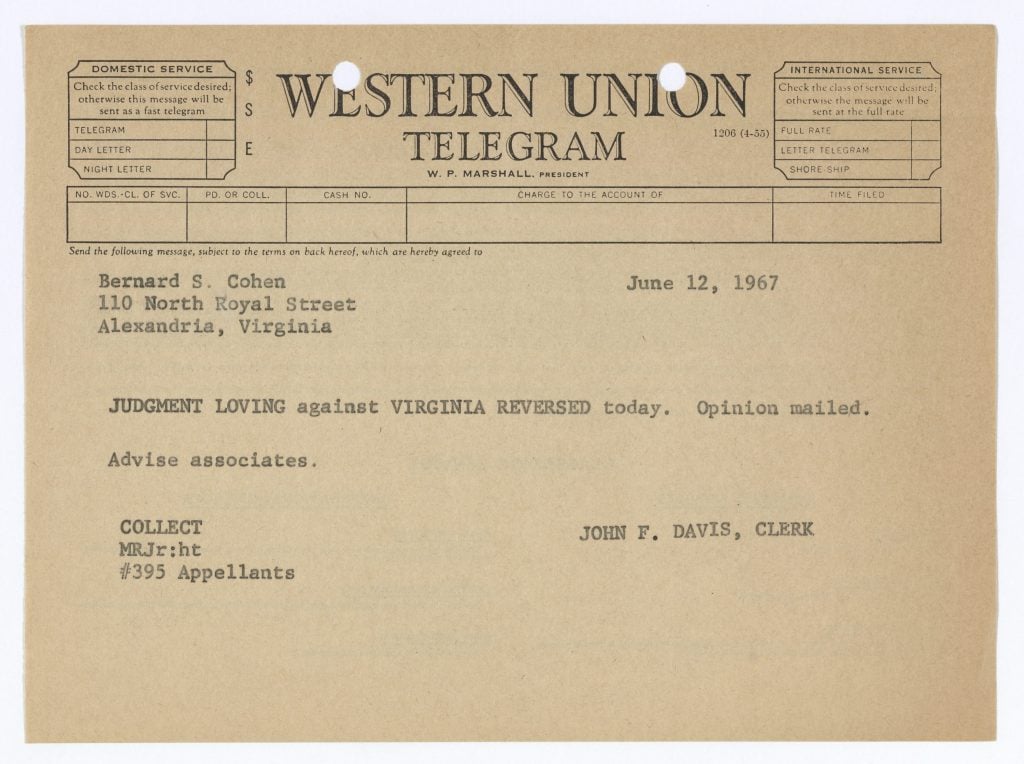

Cohen: “When the case came down, we called them on the telephone, told them of their victory. It’s hard to explain, but it was subdued glee that they expressed.”

Chief Justice Warren, in the court’s June 12, 1967, opinion: “Marriage is one of the ‘basic civil rights of man,’ fundamental to our very existence and survival. To deny this fundamental freedom on so unsupportable a basis as the racial classifications embodied in these statutes, classifications so directly subversive of the principle of equality at the heart of the Fourteenth Amendment, is surely to deprive all the State’s citizens of liberty without due process of law. The Fourteenth Amendment requires that the freedom of choice to marry not be restricted by invidious racial discriminations. Under our Constitution, the freedom to marry, or not marry, a person of another race resides with the individual, and cannot be infringed by the State. These convictions must be reversed.”

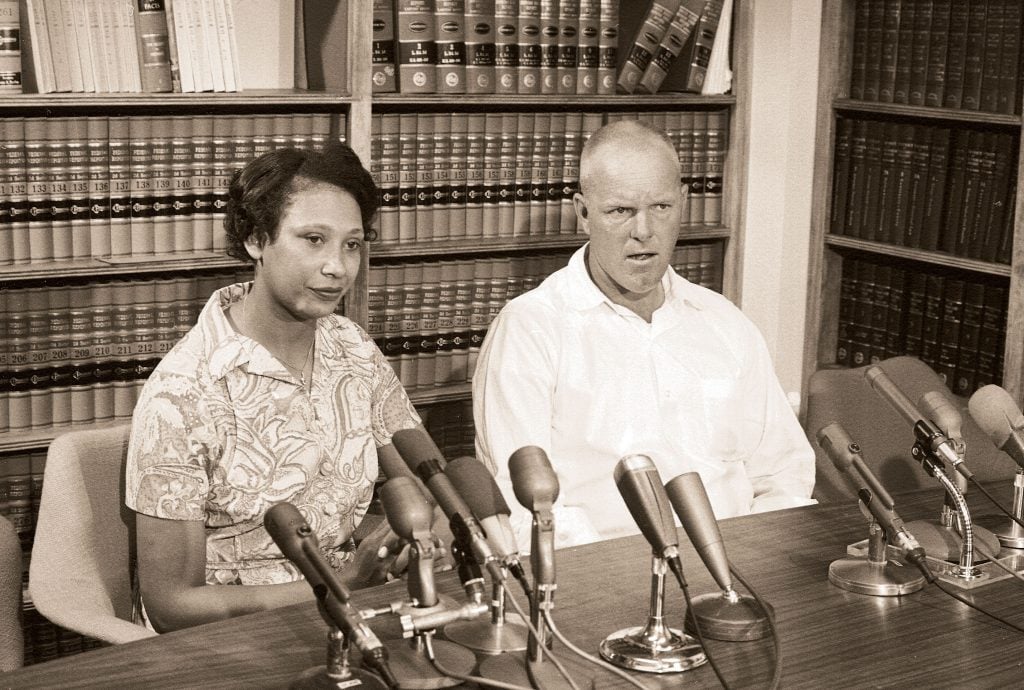

Hirschkop: “The next day, a press conference was held in our office in Alexandria. I remember I hugged Mildred for the first time in all the years I had known her.”*

*Hirschkop on how unusual the mechanics of the Living case really were: “We held no trials. The Federal Court had one motion to dismiss. There was a hearing in the Virginia Supreme Court, there was a hearing in the United States Supreme Court. We had three hearings in the whole bloody case. It was unusual that way. There was only one hearing that Lovings ever attended.”

Daughter Peggy Loving, in The Loving Story: “[The state] barked up the wrong tree. I guess that they thought [my parents] were poor and low-class, as the sheriff said they were, and that they wouldn’t do anything.”

Buirski: “They went back to Virginia with their family. Mildred continued to live in the house that Richard built for her, and she lived there for the rest of her life, surrounded by her family.”

Forty-eight years after the decision, gay-rights advocates repeatedly invoked Loving v. Virginia on their path to legalizing gay marriage in the Supreme Court case Obergefell v. Hodges.

Hirschkop: “The defenses were very much along the same line. The case of mixed marriage or same-sex marriage—they always start with the children.”

Cohen: “I would say the effect of Loving on gay marriage is a major institutional decision in American constitutional law.”

Kroll: “When I talked to Jeff about the movie before we started, it was a few months before the Supreme Court ruled on marriage equality. [We wondered] what happens if that’s resolved by the time the movie comes out. He was sorta like, ‘It doesn’t matter, because this movie is really a love story.’ [But] this movie now, because of the race stuff that’s been playing out over this last year—whether it’s police brutality or the Trump vibe that feels very present in the country right now—it all of a sudden takes on this other resonance.”

Buirski: “Sometimes for every two steps forward, you take one step back, and I think that’s what’s going on now. I’d like to think that this is part of the conversation. These issues are still out there, and festering.”

Phil Hirschkop and Bernie Cohen worked on the Loving case for almost a decade, pro bono. Hirschkop went on to argue major civil-rights cases across the country. He still practices law in Virginia. Cohen continued to practice law and served in the Virginia state legislature from 1980 to 1995. He’s now retired.

Richard Loving was killed by a drunk driver in 1975, seven years after the high-court ruling.

Mildred Loving was injured in the crash but survived. She lived her life privately but openly championed the right to marry for all Americans. On the 40th anniversary of Loving in 2007—a year before her death—she released the following statement about marriage equality:

“When my late husband, Richard, and I got married in Washington, DC in 1958, it wasn’t to make a political statement or start a fight. We were in love, and we wanted to be married. . . . [N]ot a day goes by that I don’t think of Richard and our love . . . and how much it meant to me to have that freedom to marry the person precious to me, even if others thought he was the ‘wrong kind of person’ for me to marry. I believe all Americans, no matter their race, no matter their sex, no matter their sexual orientation, should have that same freedom to marry. . . . I am proud that Richard’s and my name is on a court case that can help reinforce the love, the commitment, the fairness, and the family that so many people, black or white, young or old, gay or straight, seek in life. I support the freedom to marry for all. That’s what Loving, and loving, are all about.”

This article appears in the November 2016 issue of Washingtonian.