In the winter of 1995, Rick Yount was getting divorced, sleeping on a friend’s couch, and working 12-hour days as a social worker for abused children. To cheer him up, friends surprised him with an eight-week-old golden retriever. He thought they were crazy—rightly so, as giving pets as a gift is nearly always a bad idea. But not wanting to seem ungrateful, he smiled and thanked them. He named the puppy Gabriel—Gabe for short.

Soon after, he got a work call about an 11-year-old who was being removed from his mother’s custody. When Yount picked him up, Gabe in tow, the boy was crying uncontrollably. A mile into the drive, he fell silent. “I looked in my rearview mirror,” Yount says. “What I saw was a puppy with his head in this kid’s lap.”

From that day on, Yount regularly brought Gabe to work. He then joined a program that taught at-risk teens to train service dogs, and his dog became a certified therapy animal.

By now, it was 2005 and the Afghanistan and Iraq wars were front-page news. Many kids Yount was working with had trouble trusting people but easily bonded with Gabe. Yount theorized that the same might be true for veterans. Could they benefit not only from getting their own service dogs but also from training the animals themselves? The idea for Warrior Canine Connection was born.

The nonprofit is now headquartered in Boyds, Maryland, with Yount as its executive director. It also has staff at Walter Reed in Bethesda and Fort Belvoir Community Hospital. Though the wars have wound down, the Department of Veterans Affairs reports that as many as 20 percent of Iraq and Afghanistan vets suffer from PTSD, and Yount says there’s a dire need for more research into ways to help them.

While lots of groups give service dogs to vets, Warrior Canine Connection is unique in that vets are involved in every step. They socialize the puppies as newborns, begin training them when they’re a month old, and adopt them when they’re about two. (Until then, foster families house the dogs.) Up to 60 veterans work with every dog trained. To date, that equals more than 4,000 people.

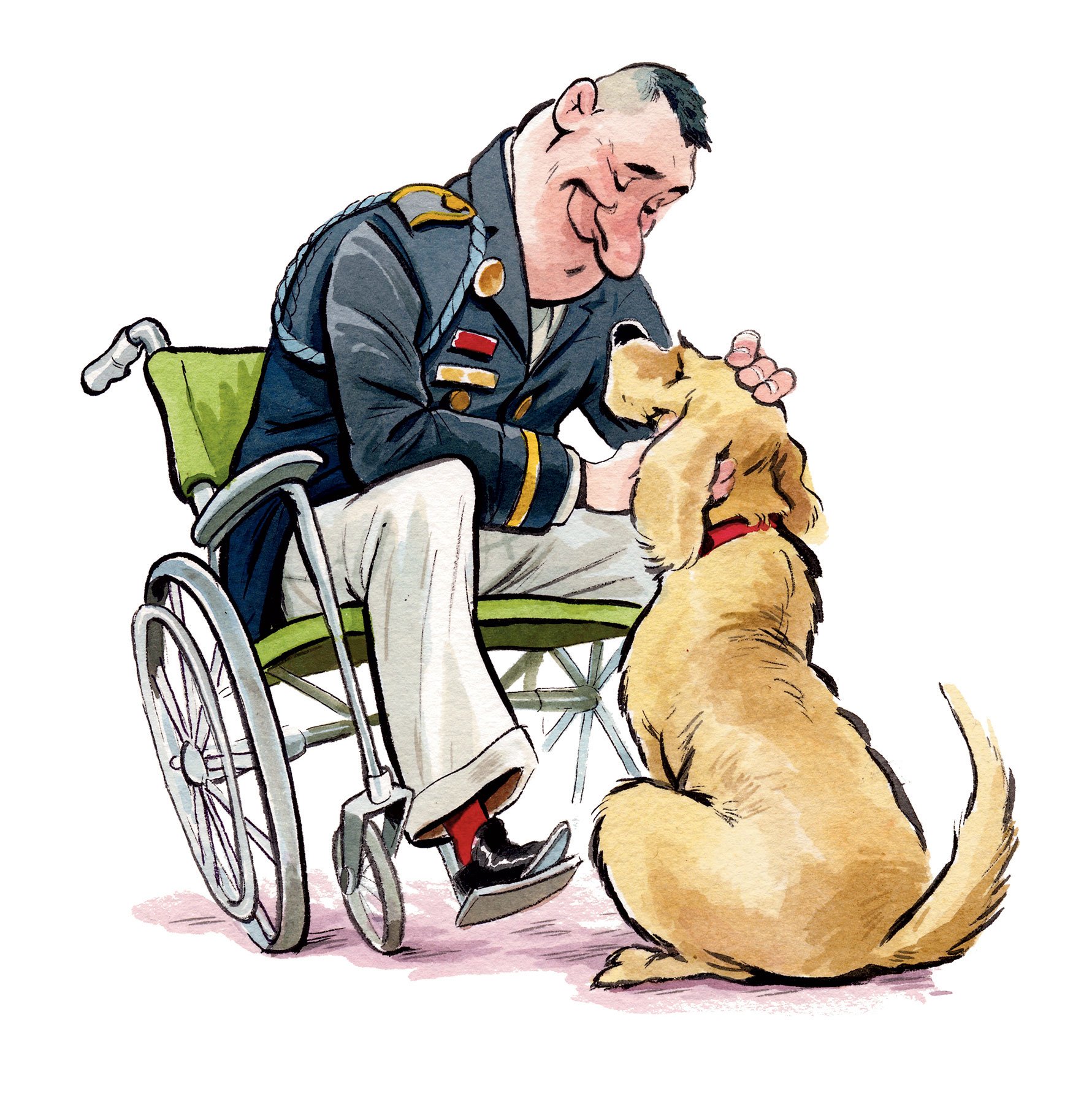

Most dogs get adopted by vets with physical disabilities, but the training part of the program is designed to be therapeutic for people battling war’s psychological toll. The trainers are taught to build relationships with the dogs through patience and affection—skills easy to forget amid the stress of combat.

Nick, a 30-year-old ex-Marine who requested that his last name not be used, returned from Afghanistan with severe PTSD. He says that when he began training a retriever named Penny, his symptoms—panic attacks, sleep problems, anxiety, anger—began to subside. Eventually, he regained enough of his mental health that Warrior Canine Connection deemed him a suitable adopter. He could keep Penny.

Now four, Penny assists Nick, who also has a back injury, in physical ways—turning off the lights, retrieving his phone and keys—but her best trick is her knack for calming him down. When Nick gets anxious, his leg twitches. Penny interrupts with gentle nudging, thwarting a full-blown panic attack.

That dogs make people happier might seem like common sense, but Yount says there’s surprisingly little awareness of the positive effect of animals on PTSD sufferers. It’s therefore tough for programs like his—which depends on donors—to qualify for government funding. Still, two new studies of dogs and PTSD are under way, including one with the University of Maryland.

When he returned from Afghanistan, Nick says, “it was always the same process: go through some therapy, and here’s some pills, go through some therapy, and here’s some pills.” He credits Penny with speeding up his recovery—plus she fetches bottles of water from the fridge.

This article appears in the November 2016 issue of Washingtonian.