Washington has long endured a culinary identity crisis—the crisis being a lack of a culinary identity.

We’re neither distinctly Southern nor distinctly Northern in our cooking traditions and can’t claim the most prized Mid-Atlantic ingredient, the Chesapeake blue crab (thanks, Baltimore). We’re known for an abundance of steakhouses geared toward expense-account diners, but even those places don’t have a singularly Washingtonian cut; most downtown meat joints are out-of-town chains. Our most recognized dishes are half-smokes and mumbo sauce—20th-century creations that reflect the District’s African-American roots but don’t represent a larger, identifying cuisine such as jambalaya in New Orleans or Memphis-style barbecue.

All of that said, a lack of culinary identity can be a good thing. It’s partly why Washington has become a great modern-day restaurant town—an exciting place to eat, filled with a broad and distinct variety. It’s why Bon Appétit named Washington 2016’s “restaurant city of the year.” Ambitious chefs who open the kind of “fearless” neighborhood eateries that the magazine applauded aren’t beholden to local tradition (though local ingredients still dominate). Instead, chefs are free to innovate, as diners see at Rockville native Aaron Silverman’s Pineapple and Pearls. They can return to their roots, as at thriving ethnic eateries in Eden Center’s Little Vietnam or Annandale’s Koreatown. While diners’ expectations have risen with the quality of restaurants, there’s no expectation of what Washington-style cuisine should be.

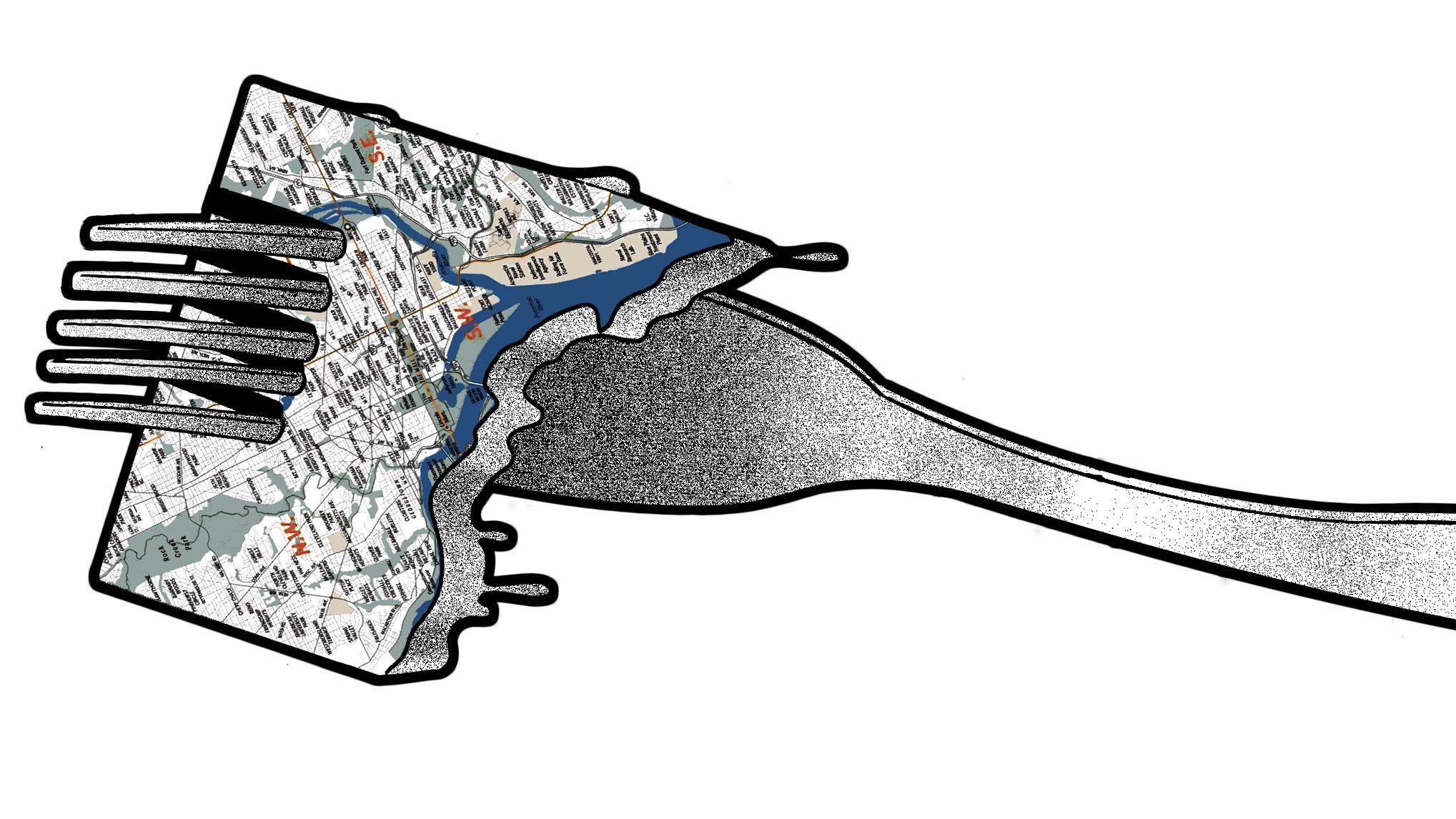

Unlike Philadelphians or San Franciscans—who get exhausted having to have an opinion on the proper way to serve a cheesesteak or bake a sourdough—we’re free to think about our own tastes. Without a deeply rooted food identity, Washington has become a true melting pot of ingredients and styles, traditions and innovations—all befitting a great food nation’s capital.