When we interviewed Cole, he was weeks away from taking over as the ACLU’s national legal director, and preparing to fight President Donald Trump. Over the weekend, his team of lawyers saw their first battle, when the ACLU sued the administration on behalf of visa-holders detained under Trump’s executive order banning travel into the US from seven Muslim-majority countries. On Saturday night, the ACLU won a temporary injunction blocking the deportation of people detained at airports nationwide.

Last summer, the American Civil Liberties Union announced that Georgetown Law professor David Cole would become its national legal director. The change wouldn’t happen until January, but Cole began envisioning the headway he’d make once Hillary Clinton’s liberal-leaning Supreme Court nominees were confirmed.

Instead, he took office the same month as an administration he deems potentially the most dangerous in US history. Rather than plotting progress on voting rights or privacy, civil libertarians will be playing defense. “See you in court,” the ACLU declared on its website the morning after the election.

Cole began his legal career defending immigrants from deportation, challenging restrictions on AIDS-education funding, and fighting for reproductive freedoms. He joined Georgetown Law’s faculty in 1990 but kept practicing. His Supreme Court wins include two defenses of the First Amendment right to burn the American flag—something Donald Trump recently said should lead to revocation of citizenship.

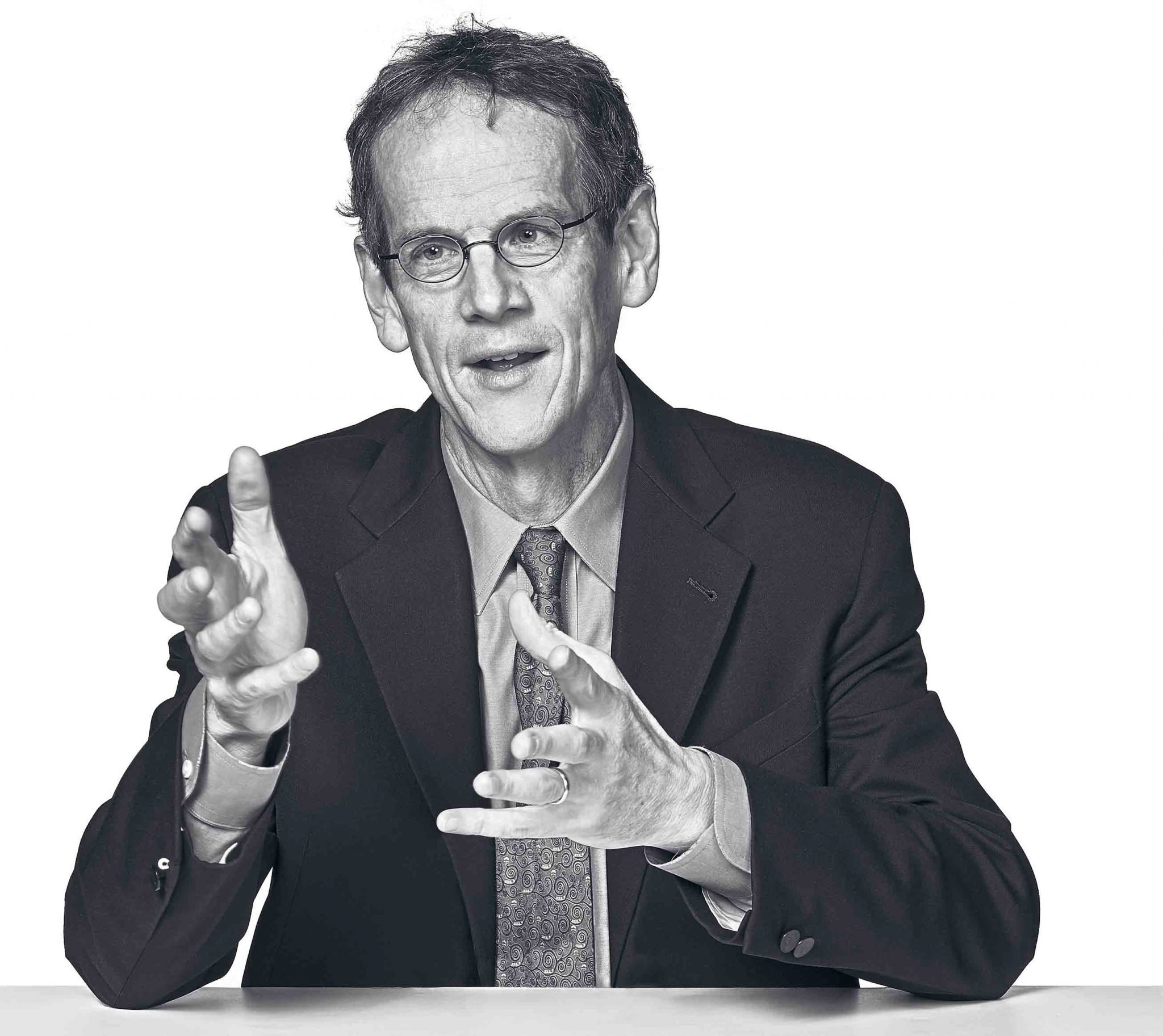

The new job requires Cole to split his weeks between New York and Washington—where his wife, Nina Pillard, is a federal judge. Managing the ACLU’s 300-plus staff lawyers takes up most of his time, but he still plans to litigate some cases himself. We talked just before Cole started at the ACLU—in his corner office at Georgetown Law, above the babel of I-395 construction—about where and how he imagines fighting for the Constitution in the next four years.

So what was the morning of November 9 like for you?

About as disappointing a day as I’ve had in my legal career. I sort of imagined I would be going to head up the legal department of the ACLU with the possibility of a liberal majority on the Supreme Court for the first time in my career. I went to law school in the 1980s and was taught by professors whose view of constitutional law was shaped by the Warren court, which was liberal—pushing for progressive reform—and put equality above all. Then they threw me out into the world to practice law under a Supreme Court that for my entire career has been dominated by conservative majorities. The kinds of things that Trump has proposed are deeply disturbing to anyone who cares about equality, liberty, dignity, and freedom.

On the other hand, I’m ready to fight. It’s times like this, with leaders like Trump, when groups like the ACLU are most needed. So in a way, what better job to have than to wake up every morning knowing I get to push back against threats to constitutional rights?

How has the election changed how you’re strategizing for the new job?

Well, we threw out all those memos about constitutional doctrinal developments under a liberal-majority Supreme Court. We’re now planning for challenges to the kinds of initiatives that Trump promised his supporters, and we’re gearing up to identify people who can help us in fighting whatever the next challenge is. It’s a little difficult to predict what he’ll do, because every morning he does something that surprises us. So you can look at what he said on the campaign trail—and we have—but then he comes up with new ones, like throwing flag burners in jail and stripping them of their citizenship.

Your most recent book, Engines of Liberty, came out before the election, but it makes the argument that citizen activists are really the ones in control of constitutional law. That feels particularly relevant now, given how panicked and powerless many people feel.

The point of the book is that constitutional constraints, constitutional principles, are meaningful and do work, if and only if citizens get engaged, get involved, and work with civil-society organizations that are committed to those principles.

Citizens who are concerned about Trump ought to be reaching out to the organization they care most about. Whether environmental or women’s rights or religious rights or civil rights, it’s the organizations that exist now—and that will presumably be created to fight back—that are the way we can do our part in ensuring Trump does not do the kind of damage he promised to do.

How do you talk to Washington’s establishment about grassroots, civic engagement without getting written off as an idealist?

The really sophisticated and effective advocates understand the power of people. One of the stories I tell in the book is the story of the NRA. How did they achieve what they’ve achieved? Through engaging members and encouraging supporters to act, to call their members of Congress. It’s not because of money—it’s because they have people who are willing to fight.

How did the NRA achieve a constitutional individual right to bear arms in 2008 [with the Supreme Court’s ruling in District of Columbia v. Heller], when in 1991 Chief Justice Warren Burger, a Republican conservative, called the notion that the Second Amendment protects an individual right to bear arms one of the greatest frauds perpetrated on the American people in his lifetime? The NRA did that through this multifaceted advocacy campaign, most of it starting at the state and local level.

By the time the question got to the Supreme Court in 2008, the NRA—through what you might call grassroots work—had gotten the vast majority of the states to recognize an individual right to bear arms, had gotten Congress to recognize it, had gotten the Justice Department to recognize it. The Supreme Court was just along for the ride.

So I’d say look at the evidence. Look at how change happens.

In thinking about the battles you’ll choose at the ACLU, what areas are at the top of your mind?

In terms of defending constitutional liberties against a Trump administration, our job is, by definition, significantly reactive. We don’t know in advance where and how he’ll overreach. We’ve been preparing in those areas where there’s really no doubt he’ll take measures, like immigration and reproductive freedom, and very likely national security and surveillance. Those are areas where, odds on, he’ll be engaged in an aggressive way, and we need to be ready.

To the extent you can prepare, what does that look like? Is it boning up on precedents in those areas?

Yeah, it’s thinking about what might he do to crack down on immigrants in the way that he has proposed, and what are the available legal arguments? So if he engages in measures that target Muslims, there are very strong religion-clause precedents that say the government can neither favor nor disfavor a particular religion, and the constitutionality of the government’s action turns on its intent, not just on the face of the law. So we would look at the kinds of things Trump has said as evidence of his intent in targeting Muslims.

You’re likely going to see more aggressive effort on the part of the administration to enlist state and local law enforcement in identifying illegal immigrants, so we would work with state and local officials to educate them about the real downsides of making the police force into an immigration force.

Historically, the ACLU has represented white supremacists in protecting their free speech. Do you anticipate taking more of those cases given the apparent resurgence in white nationalism?

It’s certainly possible. That’s one of the things the ACLU has long stood for—the right of free expression, including of those with whom we disagree. And yeah, there may be more of that.

But is there any limit? The recent dissemination of fake news—what happens in reaction to it, like the gunman at Comet Ping Pong— shows how dangerous words can be.

The ACLU does not take the position that the right of free speech is absolute. We recognize there are points beyond which people cannot go. True threats are not protected under the Constitution. Incitement of lawless action is not protected. But fake news? The difficulty with regulating fake news is that then you are empowering someone to determine the truth for the rest of us, and that’s a really dangerous proposition. I don’t think we would be comfortable with the government regulating the New York Times or Washingtonian and saying this is true and you can publish it and this is false and you can’t publish it. Similarly, I think there are concerns with empowering an entity like Facebook to determine what’s true and what’s false.

We do better as a society by responding to false accounts with more speech showing that they’re false than with suppression. The theory of the First Amendment is you trust the marketplace of ideas.

Coming out of this campaign season, the marketplace of ideas just seems . . . .

Yeah. It’s challenged.

But you remain optimistic about it?

I am cautiously optimistic. I do think there is a significant part of the body politic that understands and values deeply the Bill of Rights and will engage to defend those rights. Do I believe in the marketplace of ideas? It may not be a perfect system, but it’s better than the alternative, if the alternative to a free exchange of ideas is empowering an authority to determine for us what the truth is and to regulate it.

A lot of Washington lawyers talk about their law-school days and how they thought they’d work in social justice. Inevitably, they end up at corporate firms. How did you avoid that?

Partly because I wanted to be a writer, I wasn’t worried about getting a law-firm job the way a lot of other people are. I feel—and I think Nina does, too—that we’ve been very fortunate throughout our legal careers to fight for what we believe in every day of the week. That’s a real privilege.

This article originally appeared in the February 2017 issue of Washingtonian.