It’s no secret that the leisurely jog has given way to sometimes brutal exercise sessions in the fitness routines of über-competitive Washingtonians. But are SoulCycle, CrossFit, triathlons, and other hardcore workouts wreaking havoc on our bodies, especially as we enter our forties, fifties, and sixties?

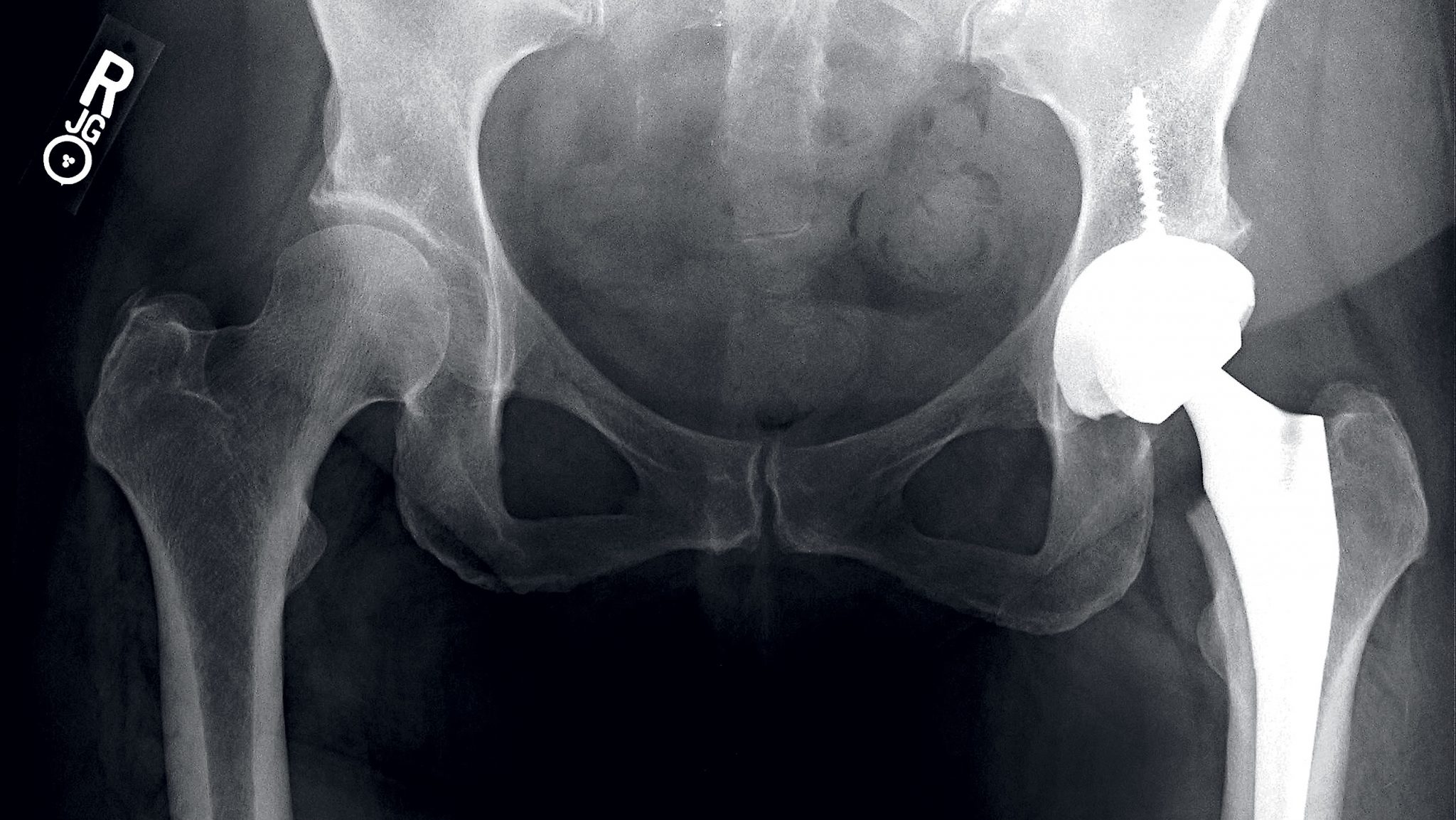

From 1993 to 2009, the number of Americans undergoing total hip replacement has more than doubled, while total knee replacements have tripled, according to a study by the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. Researchers anticipate that by 2030 the number of surgeries for ages 45 to 54 could increase six-fold for total hip replacements and as much as 17-fold for knee replacements.

At the same time, the number of Americans participating in competitive sports for fun has risen rapidly: In the past 25 years, the number running road races increased from 5 million finishers in 1990 to 19 million–plus in 2013. More than 30 percent of the 2015 finishers were age 45 or older. Participation in triathlons has seen a similar surge—almost 400 percent between 1999 and 2012—with more than 40 percent of all participants 40 or older.

Are these increases linked or merely coincidence?

When Maura Keaney of Arlington was told she needed a full hip replacement, she had “no doubt” that her 30 years of recreational soccer had played a role. The daughter of an Air Force colonel, Keaney moved often during childhood. She says playing soccer became her “little strategy for making friends and meeting people” in each new place. Keaney began playing when she was five and eventually was on her high-school and college club teams. In her twenties and thirties, she played three or four games a week, year-round, in soccer leagues.

At 41, after the birth of her second daughter and unable to walk far without pain, Keaney underwent a total hip replacement.

Scott Faucett, a DC orthopedic surgeon specializing in knee and hip replacement and preservation, says that participating in sports can wear down joint cartilage before its time—a condition known as osteoarthritis—resulting in pain and joint damage.

So should we ditch the dumbbells and sleep through morning spin? Nitin Goyal, an orthopedic surgeon at the Anderson Orthopaedic Clinic in Arlington, says the benefits of exercise still far outweigh any risks.

“Activity is good because it keeps our weight down and keeps us healthy,” he says. Increased obesity in this country is another reason physicians think joint replacement has gone up. More weight means more force on knee and hip joints over time.

But there are smart ways to exercise and things you can do to prevent joint damage.

***

Goyal believes that the simultaneous rise in recreational sports and in knee and hip replacements is likelier due to the fact that middle-aged patients are now less willing to limit or modify their activities. “We’re feeling pain more because we’re doing more—we want to be active,” he says. Twenty years ago, people accepted that their activity level might decline as they aged. Today, in contrast, “a 50-year-old who was running on a regular basis a couple of years ago isn’t willing to be just walking.”

Improvements in implant technology over the past decade also explain the dramatic rise in surgeries. Manufacturers have developed what Faucett calls “revolutionary plastics,” with wear rates about one-tenth of those used in implants 10 or 15 years ago. Both Faucett and Goyal say the new implants are expected to last more than 30 years, at least a decade longer than older ones. This, combined with improvements in surgery—now less invasive, less risky, and with reduced recovery times—has made doctors and patients more willing to consider replacement at an early age.

Which may be fitting, because local physicians are especially seeing the results of our “play hard” culture in high-school athletes.

Faucett, a doctor for the US Ski and Snowboard teams and various local sports teams, is seeing patients in their teens and twenties with knee and hip injuries due to intense athletics. There’s a growing concern in the medical community regarding “early sport specialization,” or the increasing practice of focusing on a single sport from a young age. Kids who often play one sport year-round on school, travel, and “select” teams risk severe injuries from repetitive overuse.

“Sports like tennis and hockey—those that exert excessive stress on hip joints—are more likely to cause injuries that may lead to hip replacements later in life,” Faucett says. These risks are much higher for those playing a single sport frequently or intensely during childhood or adolescence, when growth plates—which produce new bone tissue and determine the length and shape of bones in adulthood—are forming. “The damage may not start causing pain until your late twenties or thirties,” he explains, noting that these types of sports-driven damage to joints “generally don’t develop if you start the sport after development is complete.” That typically happens around age 16.

Seventeen-year-old Jack Phillips, a senior at School Without Walls in DC, began to experience pain in both hips in middle school. Now an elite high-school basketball player, he started playing at age six and started feeling hip pain around 11 or 12. “At first it was just slight tweaks in the hip flexor muscles or with high-knee exercises,” he recalls. “I never thought it was anything to be worried about.” He became more serious about basketball in middle school, playing more often and with more intensity. In high school, he’s on the varsity squad, in a private travel league after the regular season, and in basketball camps during the summer, with hopes of earning a spot on a college team.

In the first regular-season game of his junior year, and following a summer in which he described “training harder than I ever had before,” Jack felt a sudden pain, as if “someone was stabbing a sharp object into the front of my hip.” He later found he couldn’t raise his knee to walk up the stairs.

He and his parents, Roy and Anne Phillips, consulted with Faucett, who diagnosed Jack with bilateral hip impingement. While the teen didn’t need total hip replacement, he did need to have his hips surgically repaired.

“My options were to lay off sports and take it easy for life and get physical therapy or go ahead and get surgery and fix the underlying problem,” Jack says. “It was a no-brainer for me because I plan on being athletic and very active for as long as I can.”

Then 16, he had surgery, one hip at a time, in December 2015 and March 2016. He was cleared to resume basketball in September. During his first regular-season high-school game in November, he scored 26 points, with multiple assists. “I felt athletic and was jumping high,” he says. “I’m not 100 percent, but I’ll be there really, really soon.”

“Sports are important to play—it’s important for us to promote being active,” Faucett says. However, especially with young children, whose bodies are continuing to grow, “we have to manage the intensity that they’re playing, the level that they’re playing, the frequency so they get time to rest, and the variety.”

Keaney no longer plays soccer but has coached her eight-year-old daughter’s recreational team in Arlington for three years. “I’m trying to encourage her to play basketball during the winter to change things up,” she says, “but she just wants to play soccer all year.” Yet, she adds, “I think I will be more aware of when [she and her sister] are sore. They need to rest more. I always thought I should play through the pain.”

How to Avoid Joint Damage

While more athletes and weekend warriors are undergoing hip and knee replacements, there are ways to prevent problems in the first place.

➜ Ease into any new workout. “Overuse injuries tend to stem from people not having the endurance in their muscle and developing injuries in their tendons. That then can cycle into other issues,” says Scott Faucett, a DC orthopedic surgeon. Those “12 week” training programs for running a road race, for example, aren’t right for everyone: “It may take some people 32 weeks to work up to that distance.”

➜ Change up your workout. Nitin Goyal, an orthopedic surgeon in Arlington, says that when people stick to one repetitive exercise routine—especially running—they’re likely to experience joint pain. Take a day off from running to do yoga or swim, for example.

➜ Watch your form. Consider group exercise or one-on-one sessions with trained instructors who can watch you work out and can alert you to improper form that could result in injuries.

➜ No gain with pain. “It’s normal to feel a little bit of fatigue, but you should not be feeling pain” after exercise, Faucett says. “A muscle that’s fatigued is like a rope—it doesn’t have the ability to contract and relax. A muscle that’s not fatigued has an ability to absorb more impact, with less impact on your joints.”

This article originally appeared in the February 2017 issue of Washingtonian.