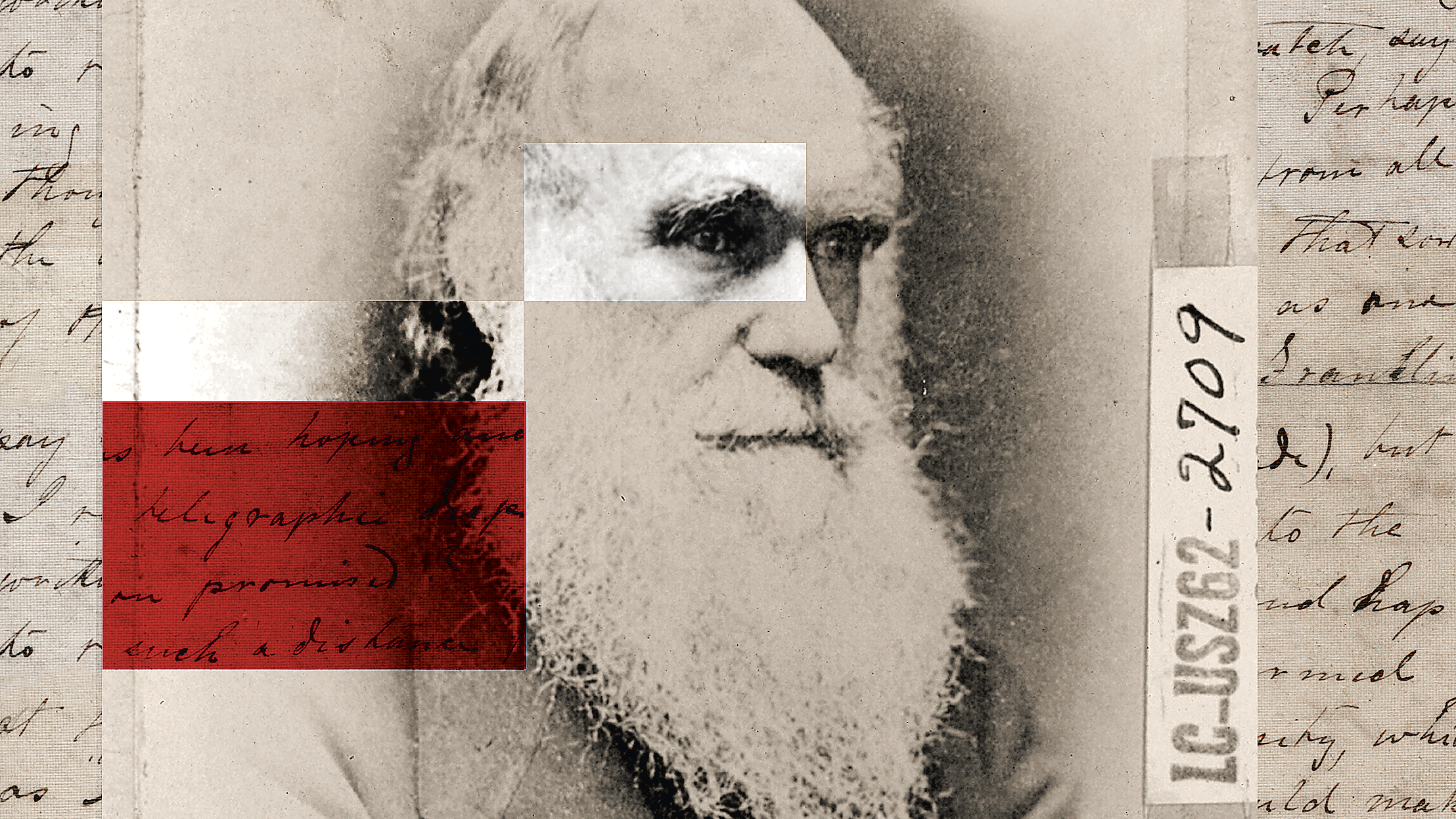

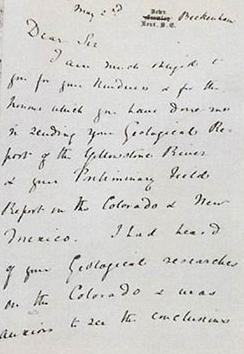

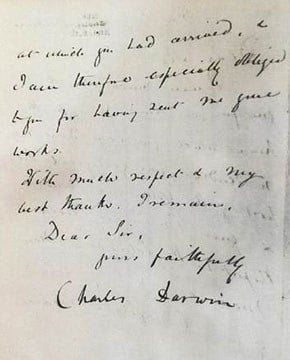

The FBI released a quick but curious bit of local news in June: Agents from its Art Crime Team had recovered a 141-year-old thank-you note, written by Charles Darwin, from a house in Northwest DC. The letter had been missing from the Smithsonian since 1978.

It wasn’t a vital piece of correspondence, just one of thousands Darwin wrote to fellow scientists over his lifetime. Perhaps that’s why no one at the institution had realized it was missing—and why the people who had the letter didn’t know they did.

The story of the discovery turns out to be more interesting than the letter itself. It begins in 2015, when Keke and John Anderson returned home from vacation. John Anderson, now 95, isn’t your average Washingtonian: The former Republican congressman ran for President in 1980 as an independent, winning an impressive 6.6 percent of the vote.

While the Andersons were away, one of their adult children cleaned out John’s old congressional desk, now in the garage of the couple’s Spring Valley home. Inside the desk was Darwin’s letter.

It turned out Keke Anderson had seen it before. According to an FBI report, she recognized it as a letter her son, John Jr., had brought home from a long-ago Smithsonian summer internship. At the time, he told his mother he’d removed the note before it was catalogued, meaning no one would miss it. Mom was unimpressed and insisted he return it.

Some weeks later, Keke Anderson spied the letter a second time while clearing out a drawer. This time, rather than trust her son to return it, she put it in her husband’s desk so he could bring it back to the museum. Instead, it sat there—for decades.

After it turned up last year, daughter Susan Anderson moved to return it, consulting an online legal service and then calling the FBI’s tip line. About a week later, she started texting with an agent and included a photo of Darwin’s letter. A couple of days after that, the FBI swung by to pick up the note Keke had placed in an envelope marked CHARLES DARWIN LETTER AUTHENTIC DO NOT THROW AWAY.

John Anderson Jr., now 59, worked for the Treasury Department until recently. He didn’t respond to requests for comment, but according to his sister, he and his mother were the only two who knew he’d taken the letter. “I never found out about it until the month I contacted the FBI,” says Susan. “Obviously, I knew the statutes [of limitations] had long passed and he wasn’t going to be held legally liable, but we all knew who did it. [The FBI] knew he did it, too.”

For the FBI, the letter’s recovery was a nice way to show off the Art Crime Team’s capabilities. They released a snazzy YouTube clip about how agents had authenticated the letter. In the video, special agent Martin Licciardo talks about how the FBI received a “citizen tip” and investigated.

As it turns out, it was wrong to think the letter’s existence had never been recorded. The note—which passed from its original recipient, geologist Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden, to collector and curator George Perkins Merrill, whose papers were acquired by the Smithsonian Institution Archives—had been photocopied at least once, for the Darwin Correspondence Project at the University of Cambridge.

Today its long stay inside John Sr.’s desk might be responsible for a discrepancy over its date. The FBI and Smithsonian both trace it to 1875, but the Darwin Correspondence Project says it was written five years earlier.

Now Cambridge may finally have a chance to examine the original.

Read parts from the full FBI file on the investigation below.

1 FBI Report by Washingtonian Magazine on Scribd

2 FBI Report by Washingtonian Magazine on Scribd

This article appears in the March 2017 issue of Washingtonian.