The exhibits you’ve seen at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History showcase only a small fraction of the 145 million items the museum has in its vaults. Normally reserved for research scientists, hundreds of these items are now on display in a new exhibit called “Objects of Wonder,” including a stuffed Martha, the last living passenger pigeon.

Gene Hunt, a paleobiologist who’s worked at the museum since 2005, was on the committee that decided which artifacts and specimens were interesting enough to make it in. He says each object illuminates a bigger story about nature and human history. “It allows us to show a lot of stuff that doesn’t necessarily have to fit into a single broader theme,” Hunt says.

We asked Hunt what his favorite objects were. Here are five of the highlights from the exhibit, which will be open through 2019:

Woolly mammoth flesh

In 1901, a team of Russian scientists discovered a woolly mammoth frozen in the Siberian permafrost with parts of its flesh still intact. They excavated it and preserved its pieces. Years later, one of the scientists fell on hard times and needed to sell off some of the 35,000-year-old specimen, and the Smithsonian acquired these jars of flesh, along with hair, teeth, and skin, in 1922.

Gut skin cape

This translucent garment was made by the native people of the Aleutian Islands in the 19th century. From the look of it, you’d never guess that it’s made from the gut track of seals and sea lions—a functional, lightweight material for the wet and cold environment. Admiring its craftsmanship, Russian mariners commissioned this one in the style of a European long coat, and it was later gifted to visiting captains or dignitaries. It then ended up in Island of Moorea in the South Pacific Ocean, where it was collected by the US Exploring Expedition in 1839. The explorers contributed it to one of the founding collections of the Smithsonian.

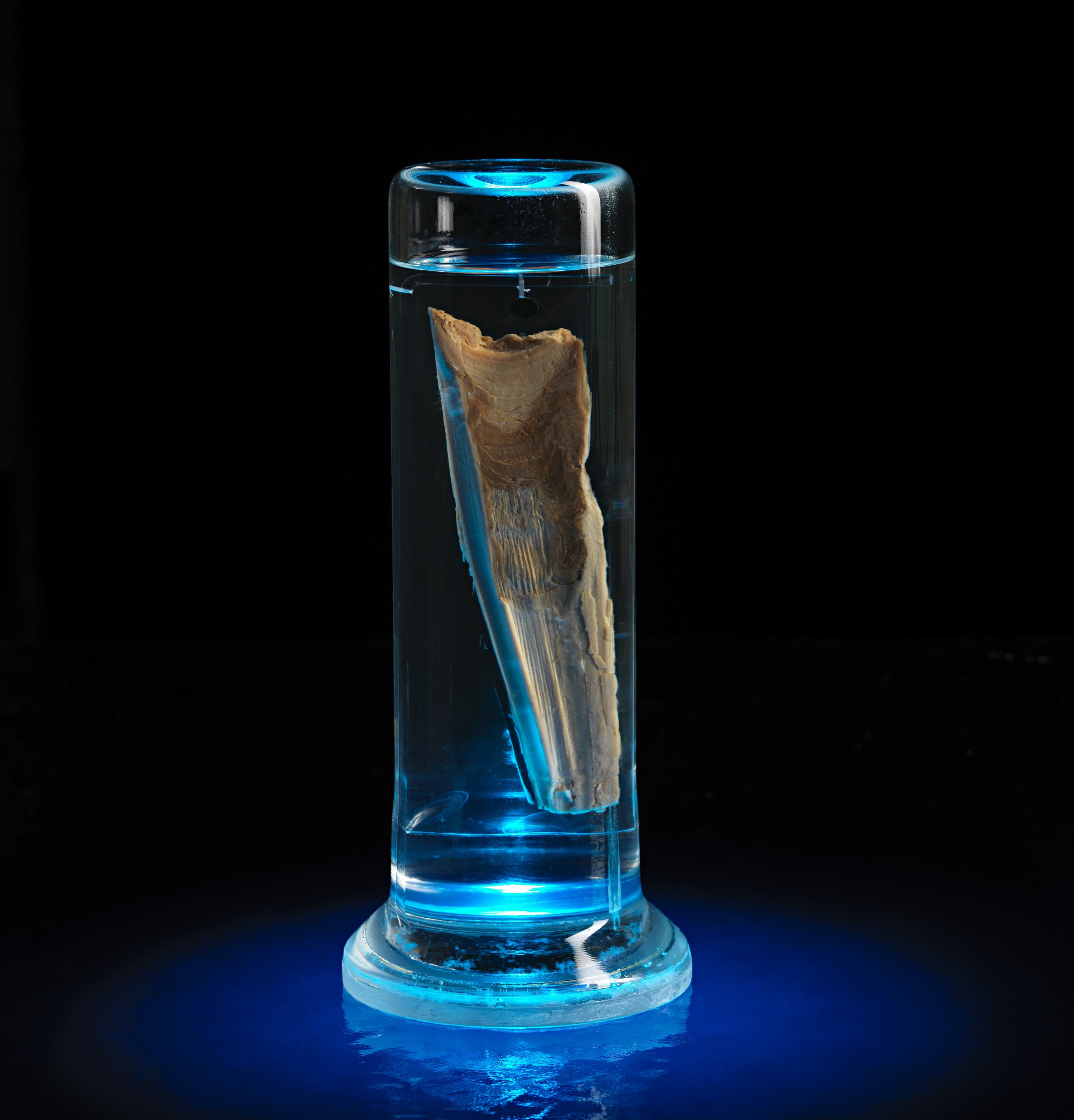

Whale earwax

All whales have this tubular buildup of earwax to protect their inner ear canal from the forces of the ocean. The Smithsonian has collected dozens of such specimens over the years (a lot of them came from the US whaling industry before it was banned in the 1960s), but it was only recently that this item became useful for science. Because the wax grows in layers, researches realized they could pull the individual layers out and analyze them for things like puberty hormones and accumulated pollutants.

Chaco canyon jars

For decades, the museum had no idea what these jars dated around 1000 AD from New Mexico were used for. Because they were covered with animal skin, researched guessed they were small drums or jars for keeping valuables. But about 10 years ago, after newly discovered pot shards were chemically analyzed, their real purpose was nailed down: they were drinking vessels for liquid chocolate. Hunt says this was a cultural practice imported from Southern Mexico, which shows a connection between the two civilizations that wasn’t known before.

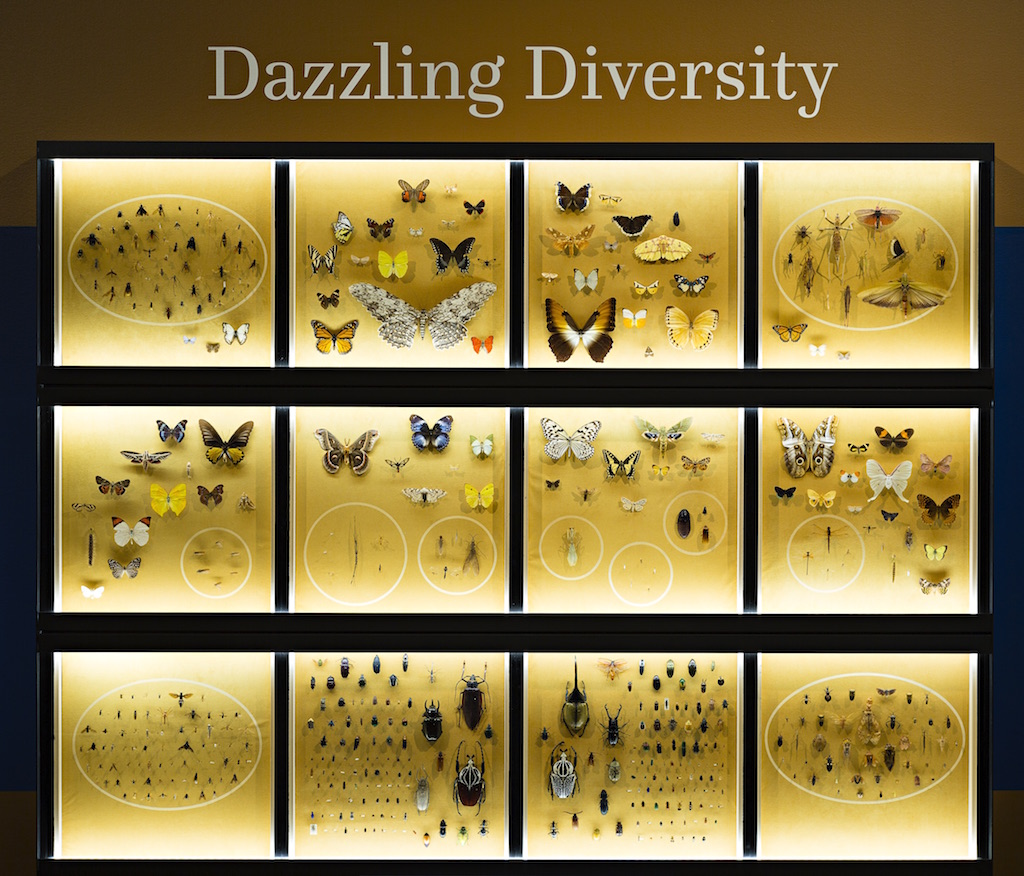

Insect diversity case

Did you know that 70 percent of known animal species are insects? And that they’re the most diverse animal group on earth? This case displays more than 500 insect specimens, which represent more than a million known insect species: beetles, roaches, locusts, butterflies, grasshoppers, to name a few. “People don’t think that much about insects but in terms of animal diversity they really dominate the planet,” Hunt says.