I am white, my wife is black, our son a rich, maple syrup brown.

Our interracial family may not share skin tones, but we are bound as tightly together as three people can be. Our love is fierce, our loyalty is fire-tested, and our values are shared.

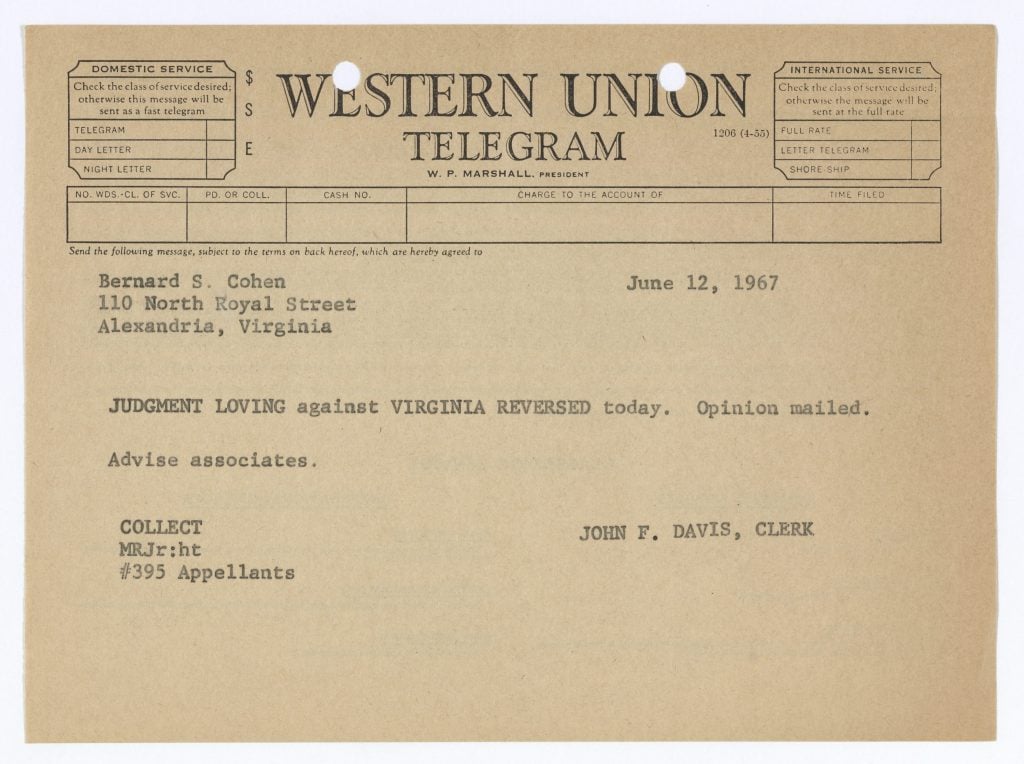

I take the very possibility of us for granted, though mixed marriages have only been legal thanks to the US Supreme Court decision Loving v. Virginia, which was decided on this date 50 years ago.

From all that I have read of the couple who brought the suit–Richard Loving, who was white, and Mildred Loving, an African-American–were not spotlight seekers or diehard crusaders. They were simply two people who loved each other and wanted the right to spend their lives together raising a family. What is now a common slogan on bumper stickers–love is colorblind–was a revolutionary statement back then.

The Lovings were married in Virginia in 1958, but only five weeks later were arrested under the state’s anti-miscegenation statute. They were sentenced to a year in jail, but granted a reprieve if they moved to Washington, DC, and stayed there for 25 years. Mildred wrote a letter to Robert Kennedy, then the Attorney General of the United States, to ask for his assistance. He referred them to the ACLU, who took up their cause and eventually won the landmark case in 1967.

In the year the decision was handed down, intermarried couples were a rarity, comprising only 3 percent of all couples. Things have changed. According to the last census in 2010, interracial households grew by 28 percent over the previous decade–from 7 percent in 2000 to 10 percent in 2010. The Pew Research Center notes that newlyweds married someone of a different race or ethnicity 17 percent of the time as of 2015. If the trend lines hold, the next census in 2020 will show that an even greater percentage of interracial couples exist.

My wife and I began dating in 2006, while we were both living in Central New York. I was in graduate school and she was working as a lawyer. Neither one of us felt dating someone who’s skin color didn’t match there own was a big deal. Our friends and families were all open and accepting of our relationship. There were no flare-ups or flashpoints over race. We were happy, so they were happy for us.

I know we are lucky. We know many interracial couples that have been spurned and assailed by those who supposedly love them. That hurt runs deep and those wounds never fully heal.

We blended our lives gracefully. Over time, I learned about the culture of her homeland, Ghana, while I indoctrinated her to the traditions of my family tree, which included Pennsylvania Dutch, Scotch-Irish, and other roots. I now own traditional kente cloth robes and enjoy eating ground nut soup with fufu, she can now say she’s tried shoo-fly pie and has full-heartedly embraced family reunions in the backwoods on Massachusetts and on a boat off the coast of Maine.

We have frank conversations about race, which can be difficult. My wife has shared stories of brutal bigotry leveled against her. Through her and others, I have come to see new perspectives on a number of racial issues, which serve as a continual reminder that even my open-minded liberalism can easily fail to truly understand certain social structures, situations and historical prejudices. These discussions fuel waking nightmares about when my son first feels the burning barbs of racism and the times in his life he may be unjustly judged or mistreated because of the color of his skin. And I worry as I watch race relations in America blaze with increasing intensity and as racists, emboldened by the new administration, reveal themselves.

But no matter what happens or the challenges my family faces, we will always have us. White, black, maple syrup brown.

All families whose colors cross and blend owe a great debt to Richard and Mildred for making it possible for us to live our love. Let us never forget that loving is loving is loving.