For most people, a lost or stolen form of identification is an easily fixed nuisance, not a calamity. While it might require waiting in a long, pesky line at the DMV and digging out a few other documents, such items can usually be easily replaced.

The process is not as simple, however, for the roughly 8,000 homeless people living in DC. Living on the streets, many people have a hard time keeping track of birth certificates, Social Security cards, or other forms of identification. And without any ID, it’s much harder to access shelter services, receive medical treatment, apply for housing, or find work.

“Any of the possible avenues out of homelessness, you’re going to need ID,” says Bob Glennon, the clinical director at Miriam’s Kitchen, a homeless shelter in the city.

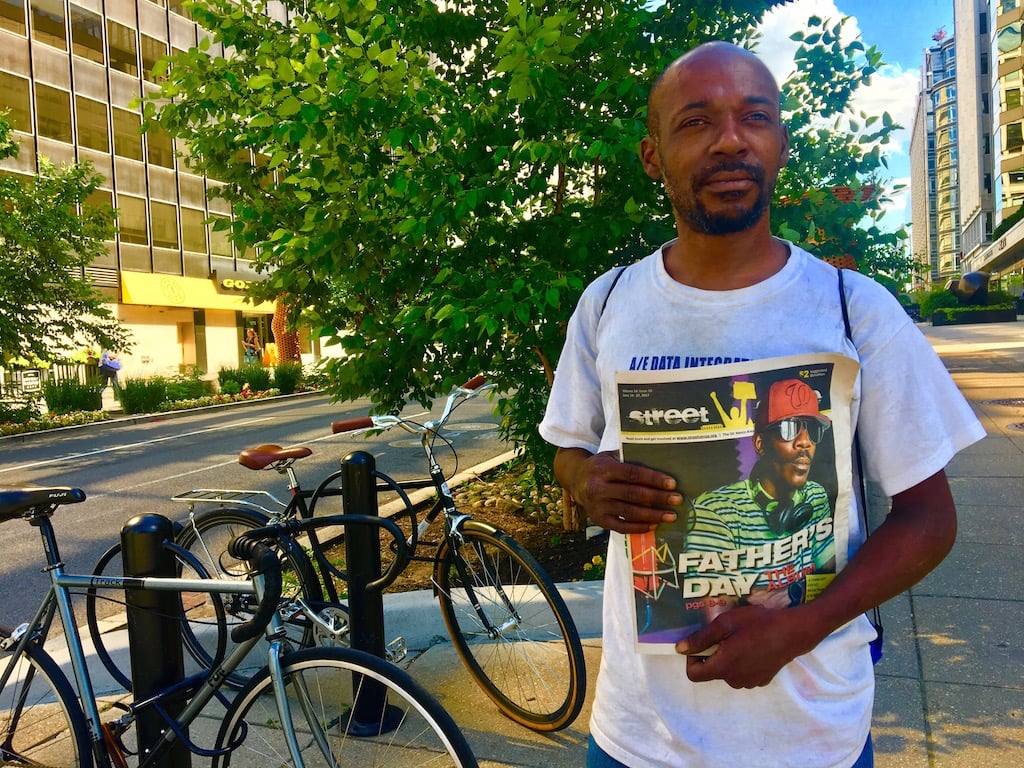

Martin Walker, 45, knows this struggle firsthand. Although Walker grew up in DC, he moved to Maryland as an adult, where he worked as a truck driver. In 2004, he lost his job and was unable to afford his rent. He ended up on the streets, and moved back to DC. Since then, Walker has spent his days selling copies of Street Sense, and his nights sleeping outside. He says he’s had a hard time holding on to important documents.

“I can’t keep anything outside,” he says. “People steal things from you when you sleep. You got to constantly be attached to your belongings. I’ve had so many backpacks stolen with birth certificates and Social Security cards in them.”

In 2014, Walker lost his commercial driver’s license. He was eager to find work as a truck driver, so he knew it would needed to be replaced. But before he went to DC’s Department of Motor Vehicles, he would need two other forms of identification–for Walker, this meant he would need a copy of his birth certificate and a card with his Social Security number.

“It’s a catch-22,” says Julie Turner, a social worker who has worked with DC’s homeless community for 30 years. “You can’t get one unless you have the other.”

Walker spent the next three years being shuffled between the city’s Vital Records office, the Social Security Administration, the DMV, and George Washington University Hospital, trying to obtain all the necessary documents to replace his license. Each office required one form of identification in order to get another. Certain offices turned him away unless he came in with a caseworker.

“It’s a tough spot,” Glennon says. “Obviously, the office of Vital Records doesn’t want to give a birth certificate to the wrong person. There’s obviously legitimate concerns about identity theft and other things.”

Even after Walker had obtained a copy of his birth certificate and Social Security card, he was expected to show proof of residency to the DMV, which was impossible for him in his situation.

“It actually felt like the District was trying to prevent me from getting my identity back,” says Walker.

Ultimately, Walker got staff from Miriam’s Kitchen to sign a voucher from the DC Department of Human Services certifying he was homeless, which allowed him to get an ID from the DMV using the shelter’s address, and eventually, a new driver’s license.

While a handful of agencies in addition to Miriam’s Kitchen provide assistance to homeless people trying to replace their IDs, the demand can be overwhelming. Caseworkers often find themselves maneuvering through regulations issued by different state and federal agencies to help their clients replace these documents, and the fees usually come out of shelters’ own finances. Glennon says that Miriam’s Kitchen recently had to scale back its ID referral services in order to focus on its housing program.

“We had to make choices about what we thought would be most impactful,” he says.

Some DC lawmakers have tried to address this issue by proposing city programs that would help homeless individuals recover their identifying documents. In 2016, Councilmembers David Grosso and Yvette Alexander introduced a bill waiving the fees for replacement of identity documents—including birth certificates and drivers’ licenses—for low-income residents. After estimating that the bill would cost $9.6 million over four years to implement, the office of DC’s Chief Financial Officer said city funds were not sufficient to cover the cost.

Grosso says it has been an “ongoing battle” to receive enough funding from the city to implement the changes he set out to make. “It’s really a prioritization question,” he says. “The vital records issue is more expensive, but the mayor could make it a priority. She just hasn’t done it.”

Mayor Muriel Bowser’s office, which only requested enough money to fund birth-certificate replacements in its fiscal 2018 budget, did not respond to requests for comment.

After all the bureaucratic hurdles he went through to get his license replaced, Walker can’t help but feel that these three years were wasted. “That’s three years of putting my entire life on hold,” he says. “I’ve slept through blizzards, hurricanes, all outside, because of difficulties trying to obtain my license.”

With a new license in hand, Walker plans to leave DC and look for work elsewhere as a truck driver. He doesn’t want to risk losing his ID and going through the same process again. He plans to write an article for Street Sense about the possibility of streamlining the identity documentation process, perhaps with a fingerprint-scanning system.

For now, though, he says he hopes fellow Washingtonians understand that this could happen to anyone–just because homeless people find themselves in this rut doesn’t mean they’re not trying to get out.

“A lot of homeless people out here like myself have been doing everything in their power for years trying to get out of the situation and haven’t been able to reach the finish line,” he says, “because they’re still caught in a loop.”

Washingtonian is one of seven DC-based newsrooms dedicating a portion of our news-gathering to a June 29 collaborative news blitz aimed at uncovering barriers and solutions to ending homelessness. See all participants’ work at DCHomelessCrisis.Press.