James Davis was by the Safeway in Adams Morgan, one of his usual spots, when he saw the attack. Just after dark on an evening in July, a 74-year-old woman was assaulted by an apparent shoplifter—kicked, punched, and hit with a shoe. At 66, Davis wasn’t much younger than the victim. But along with other good Samaritans, he raced toward the melee, chased off the attacker, and waited with the woman until the ambulance arrived. The next day, she expressed her gratitude in a message posted on the PoPville blog that thanked everyone who helped, especially “the homeless guy that sells the newspaper in front of Safeway.”

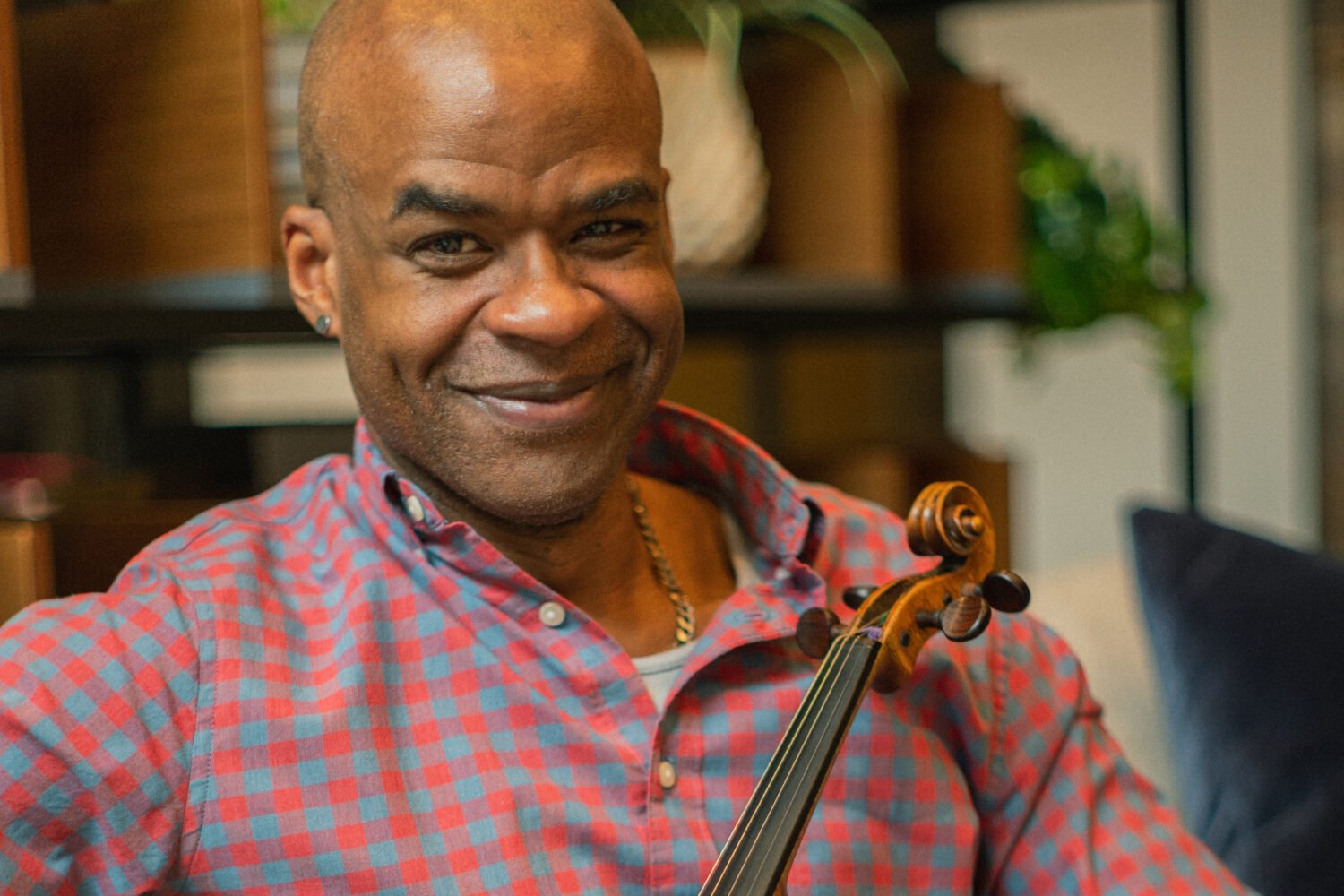

Davis actually isn’t unhoused anymore, but he is a vendor for Street Sense, the newspaper by and about DC’s unhoused community, and selling copies has changed the course of his life. Rather than sleeping on a park bench, he now has an apartment in Columbia Heights. Instead of empty pockets, he has a reliable income. And in place of debilitating depression, he has a feeling of purpose. None of it would have been possible without the things Davis learned through Street Sense.

Yet today, Street Sense is struggling to survive. Following a decline in donations, the organization announced in July that it’s laying off staff and will publish half as often. For the 100 or so unhoused people who currently sell the paper, Street Sense’s troubles a threat to something deeper than just their income. “We use the phrase around here that we define people not by their housing situation but by their talents,” says Street Sense CEO Brian Carome. “We provide people with a means to work themselves out of homelessness and to use their own skill set to move forward in life.”

Street Sense wasn’t the first so-called street newspaper; before it launched in 2003, similar efforts were already up and running in places such as New York and Chicago. But DC never had its own version—until a pair of young volunteers, Laura Thompson Osuri and Ted Henson, teamed up. Osuri had been working at the financial-services trade publication American Banker, while Henson—who’d dropped out of journalism school to follow his girlfriend here—had an internship with the National Coalition for the Homeless. When Henson arrived in DC, one of the coalition’s founding board members, Michael Stoops, put him in contact with Osuri, who had reached out to him about launching a street paper. From there, the plan took shape, and Osuri and Henson launched the organization with help from the National Coalition for the Homeless.

Initially funded by donations from friends and family, Street Sense didn’t cover just the city’s unhoused community—it was partially written and entirely sold by unhoused people, providing them with both income and skills. Today, vendors can buy copies for 50 cents apiece, then sell them for $2 or more to earn income.

The first issue hit the streets in late 2003, with a print run of 5,000. It featured an interview with Eleanor Holmes Norton and a story about congressional legislation to address homelessness. “Back then, before social media, [unhoused] people didn’t have outlets to honestly tell their stories,” Henson says. “We really prided ourselves on the fact that over half of our content was produced by people experiencing homelessness.”

One of the very first Street Sense vendors was James Davis. He hadn’t been on the streets that long at that point: Following a painful divorce, the former electrical engineer had found himself without a job or a place to stay. After several frigid nights in Franklin Square Park, he moved into the Central Union Mission shelter. It was there that he heard about the newspaper’s upcoming launch.

It turned out Davis was great at selling papers. Before long, he was earning $100 a day from his efforts. He began holding workshops in DC’s Church of the Epiphany, where Street Sense was headquartered, to train other vendors. “Instead of isolating myself and feeling sorry for my situation,” Davis says, he took pride in his achievements. “It was therapeutic.” Now he’s among the longest-tenured Street Sense sellers.

“At a moment when Street Sense is celebrating its 20th anniversary, it also finds itself in the middle of a serious financial crunch.”

Over the past two decades, more than 700 unhoused people have sold Street Sense, and the organization has worked to find additional ways to help them. Street Sense now has a caseworker who can connect them to outside services such as housing assistance, job training, and mental-health counseling. Something as simple as helping obtain a birth certificate and picture ID can make a crucial difference.

The organization’s leaders also realized they could help more people by expanding beyond the newspaper. In 2017, the nonprofit changed its name to Street Sense Media, and it now offers workshops in theater, illustration, photography, poetry, and watercolor painting. “Not everyone is born to be a writer,” says Will Schick, editor in chief of Street Sense. “But everybody has a story.”

Among those who have benefited from this expansion is Sasha, a 38-year-old mother of two who got involved with Street Sense in 2014. Though she began as a vendor, Sasha soon gravitated to theater, illustration, and filmmaking. While she was performing in plays and producing a documentary, Sasha was also addressing critical challenges in her life. With the help of a Street Sense caseworker, she was able to obtain a housing voucher and move with her daughters into a two-bedroom apartment. “I’m an artist,” she says, “so the opportunity—yeah, that’s uplifting.”

If you buy a copy of Street Sense, you’ll get a well-curated mix of news stories, personal essays, poetry, and photography. There’s a small permanent staff of reporters and writers, but much of the content is created by unhoused people. And while the overall goal is altruistic, the reporting can be quite valuable. James Davis isn’t just a great salesperson—he also once broke a significant story. In 2006, Davis told Laura Thompson Osuri about private eviction firms that would send vans to a local soup kitchen and hire groups of unhoused people. In exchange for as little as $1.25 an hour, the workers would haul out the belongings of evicted tenants.

Davis and Osuri decided to team up to report a story about the exploitative practice. “We thought it was ironic that these homeless people were getting paid to then make other people homeless,” Osuri says. Davis signed up for a shift on an eviction crew, while Osuri worked the phones. Their story—“Homeless People Hired to Evict Tenants”—resonated far beyond the local unhoused community, garnering coverage in the Wall Street Journal and precipitating a class-action lawsuit against leading private eviction firms. For Davis, the experience was thrilling. “I was making a difference in people’s lives,” he says. “I actually saw the change.”

But now, at a moment when Street Sense has been celebrating its 20th anniversary, the organization also finds itself in the middle of a serious financial crunch. Coming up with the money to keep things going has become increasingly challenging, Street Sense’s leaders say. After a spike in contributions during the Covid crisis, private donations—the group’s main source of revenue—have fallen off significantly. At the same time, the ongoing decline in downtown workers due to remote work has eaten into newspaper sales. The recent cuts to Street Sense’s staff and print schedule, Carome says, “were made to make sure that we didn’t go belly-up, to be honest.”

Street Sense’s leadership is looking at what other changes they can make to keep the organization on a sustainable path. While many other struggling print publications have reduced costs by adopting a digital-only approach, this strategy won’t work for Street Sense—because doing away with the physical newspaper would deprive its vendors of income. (Street Sense does have a website, of course; you can check out its reporting there if you aren’t able to find a vendor near you.) One idea under consideration, Carome says, is to provide transportation to vendors so they can travel to communities outside of DC’s downtown corridor and, hopefully, find more customers.

Regardless of what comes next, Street Sense’s veteran paper seller isn’t giving up on the project. James Davis hasn’t been unhoused for years, and he’s become something of a leader in the organization. (He has even served on its board of directors.) Davis no longer relies so much on the money from selling papers, as he now qualifies for social security. But about six years ago, he made a commitment he plans to keep. At the time, Michael Stoops was dying of complications related to a stroke. He asked Davis to do everything he could to keep the program alive. “And so I made that promise,” Davis says.

That’s part of why he still sells papers most days, heading to the Adams Morgan Safeway or his other favorite location, at 17th and L downtown. Pass by Davis’s spot at the right time and you’ll find him standing there with his thick stack of newspapers, sharing smiles with longtime customers and, occasionally, jumping in to try to protect a neighbor. He’ll happily hand you the latest Street Sense in exchange for two bucks, or a bit more if you’re feeling generous. Hawking the publication is his job, after all, plus he just wants to spread the word about how important the group’s work is. “The paper isn’t just for the vendors,” Davis says. “It’s for the community.”

This article appears in the September 2023 issue of Washingtonian.

![Luke 008[2]-1 - Washingtonian](https://www.washingtonian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Luke-0082-1-e1509126354184.jpg)