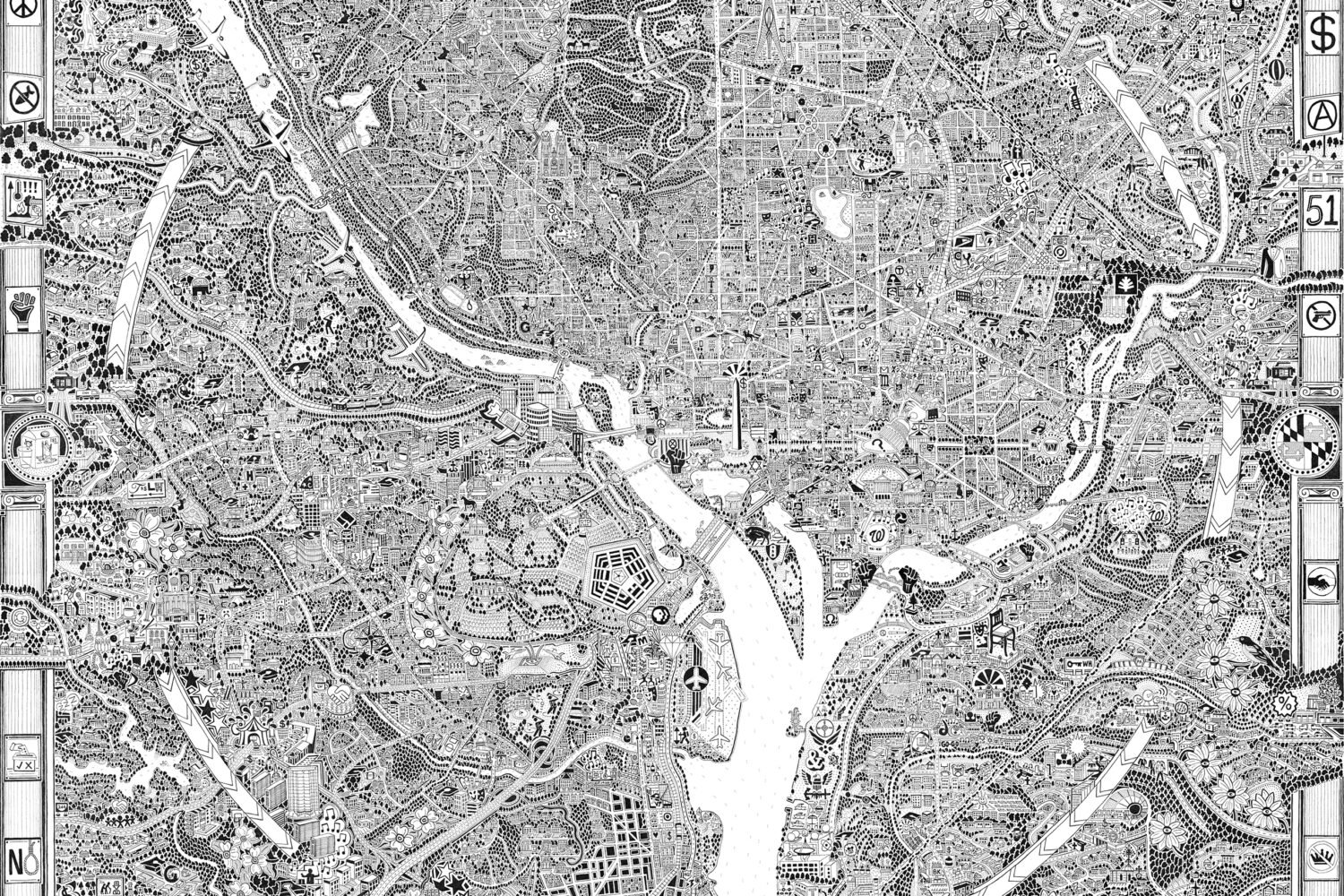

The grassy hill just northwest of the Washington Monument—the one usually dense with selfie-stick-wielding tourists—used to be, for a short and scandalous time, completely under water.

It all started with some carp. In 1877, the recently imported species was being extolled around DC, where “Carp Culture”—as the Washington Evening Star called it—was irrepressible. “Within ten years to come this fish will become, through the agency of the United States Fish Commission, widely known throughout the country and esteemed in proportion,” the commission’s congressional report boasted.

But before you esteem carp, you gotta catch carp. Smithsonian curator Spencer F. Baird, who was doing double duty as fish commish, began mass-producing mirror and scale carp, along with European tench and gold orfe, to stock the nation’s waterways. The breeding operation was based out of three shallow ponds named Babcock Lakes, after Ulysses S. Grant’s aide-de-camp, Orville Babcock, who had overseen efforts to tidy up the “terrible swamp nuisance” (another Evening Star description) that plagued the area. Congress easily approved Baird’s proposal to put the bodies of water to work.

Within a few years, the newly dug lakes were brimming with carp. The gold orfe, which resemble large goldfish, proved so popular that Congress offered them to constituents as pets. By 1894, nearly a third of DC households had their own gigantic goldies.

That’s when the grumbling started. The New York Times mocked legislators for moonlighting as pet-shop proprietors, thereby spelling the end of the goldfish giveaways. More troubling, as carp were unleashed across the country, anglers began noticing unintended consequences, such as muddiness in the water. Carp are now known to filter nutrients from mud, and the murky water they created was killing off plants, causing waterfowl populations to diminish as well. Meanwhile, under water, predator fish couldn’t see their prey.

By the late 1880s, Babcock Lakes had ceased all carp production. Meanwhile, across the country, carp-removal programs were under way to rehabilitate affected waterways. Within a decade, the Army Corps of Engineers filled the lakes, landscaping them into the terrace that greets monument visitors today.

This article appears in the July 2017 issue of Washingtonian.