Picture a time before Wikipedia, before High Times and the Vice Guide to Sex and Drugs and Rock and Roll. Before doctor-prescribed micro-dosing for middle-class moms. Before magic mushrooms were used to treat anxiety and pot could be grown on your kitchen windowsill or delivered to your door. Picture the twilight of the 1960s.

Maybe you imagine it shrouded in a ganja-scented haze of anything-goes debauchery, but it was actually a moment of drug-doing innocence—a world in which a pop hit like Donovan’s “Mellow Yellow” could convince people that smoking dried banana peels might get you high. In those strange, long-ago days, there was one place Washington turned to for plain facts about dope: an underground newspaper called the Washington Free Press. There, local heads in search of a safe path between the thrill-seeking hedonism and anti-drug hysteria of the era would pen letters to its drug columnist, Fooman Zybar, whose biweekly dispatch is believed to have been the nation’s first regularly published column on recreational drugs written by a user.

“I’ve read four of your rags on drugs, but the one on H [heroin], I appreciate the most,” a woman named Janis wrote Zybar in early 1969. “I’ve been wanting to try it, but I know better now. The psychedelic world is much better. . . . Please write about the so-called trash highs—glue, freon, amyl nitrate, instant ice, etc.”

Like many before her, Janis wondered about something else, too. Was this character Fooman for real or some kind of put-on? “Whether you’re one person or a union of several heads writing the articles,” she ended her letter, “keep going.”

Zybar’s response featured a tirade against the evil of opiates and a chemical breakdown of the toxic dangers of “trash highs,” which, he added, “are another typically American phenomenon of where the Government would rather see you dead than high, so by outlawing natural paths to a different state of mind and soul, they force you to ingest corrosive, paralyzing, poisonous chemicals on your search to discover who you are.”

Like most of his columns, it was cautionary in its advice, radical in its politics, cool-older-brother-ish in its tone (and long). But this time, he answered the question on every reader’s mind. Though he didn’t reveal that Fooman Zybar was a pen name, he clarified that the column’s author wasn’t some mashed-up composite. “Fooman is really one person,” he told Janis, “who has seen and done things that I know must be said to others. . . . F.Z.”

That’s right. Fooman Zybar took all the drugs he wrote about, from morning-glory seeds to LSD to heroin. In a sea of misinformation, he dispensed a blend of clinical and mystical advice, like William Blake working the counter of the local pharmacy. He was also one of the main reasons why, for a brief spell at the boiling point of the turbulent decade, the Free Press’s circulation soared.

Then, in the late spring of ’69, the last F.Z. byline appeared. It was one of his most euphoric dispatches from the astral plane, a column in praise of peyote. Then he was gone. No explanation, no adios. His name vanished from the masthead.

Not long after, the Free Press itself disappeared, mired in controversy and obscenity lawsuits. Carl Bernstein wrote an obit in the March 9, 1970, Washington Post, noting, “It went out kicking and screaming.”

Fooman Zybar, though, wasn’t available for comment. Word was he had fled DC one morning the previous summer, just before police raided his house. He was last seen in a beat-up convertible with a drug buddy at the wheel, headed west. For the next decade, he was off the grid. Hardly a soul in DC’s so-called free community saw or heard from their guru of good vibes.

Nearly 50 years later, the underground press is long gone and doctors prescribe pot for chronic headaches. Yet believe it or not, the real-life Fooman Zybar—actual name, Pete Novick—is still among us, living out his golden years in suburban Washington and all too happy to talk about the days when he was a star. He takes the old saying “If you can remember the ’60s, you weren’t there” and turns it upside down. He seems to remember everything.

Pete Novick is 69 now and lives in a converted coal-chute-and-furnace room in a Silver Spring apartment building. This man cave, the refuge of an unrepentant beatnik, is next to the washer/dryer area in the basement, with about as much elbow room as your average trailer home. Walk inside and you can barely maneuver between his stockpile of lab beakers, test tubes of chemicals, and vials of herbs and powders. There are medical manuals and back issues galore of Scientific American and the Old Farmer’s Almanac—“I just like playing around with chemistry and herbs and things,” he says—plus hand-scrawled calculations for experiments pinned to the shelves. A TV flickers with Mannix and other ’60s cop shows while a push-button corded phone rings out from the past.

Near the fridge hangs a yellowing front page of the Free Press from January 1969. That issue’s cover showed the staff itself, two dozen scruffy young men and women waving the peace sign outside the US Capitol to protest Nixon’s inauguration. There’s also a copy of Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited. Amazingly, it still bears an original Waxie Maxie’s record-store sticker from when Novick bought it a half century ago. The album is its own kind of totem. It helped bring him to the underground paper in the first place.

The record was in Novick’s ’50 VW Beetle, along with some pot to help enjoy the music, on the day he was driving to a friend’s and was arrested for drug possession. It was February 1967. He was 18, and two months before, he’d been booked on a similar charge after a raid at a group house where he lived with other University of Maryland students. When he pleaded his case in court—saying that marijuana was no more harmful than alcohol and that if he had a joint, he’d smoke it again—the judge was not impressed. “It’s indeed distressing for a member of the court to sit up here and look at a young American who has had all the advantages and to see that young American throw it upon the ground and stamp upon it,” the judge said.

Novick had been a student leader, a science-fair winner, a local newspaper reporter in Bowie. His stellar academics, combined with his courtroom proselytizing, turned him into a local sensation, the subject of headlines in the Washington Evening Star.

He spent the Summer of Love serving six months of a two-year sentence at a state prison in Hagerstown, shoveling string beans in the cannery and driving a dump truck full of fly ash. Every morning on the walk to the mess hall, he’d sing Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man.” One day, Novick was in the visiting room and saw the Free Press. It was a special issue about the March on the Pentagon, an October 1967 demonstration against the war in Vietnam. The paper’s curbside reporting revealed that the military crackdown against the mostly peaceful protesters had been bloodier than the mainstream media had let on. “It looked like my kind of paper,” Novick says.

Several months later, after fulfilling the terms of his parole, he showed up at the newspaper’s Thomas Circle office and told cofounder Frank Speltz he wanted to work. “Well,” Speltz said, “start working.”

The District’s most radical paper had grown from a scrappy, satirical street rag to one that covered controversies such as home rule and the proposed superhighways through the heart of the District. There were in-depth Q&As with a radical priest and a young agitator named Marion Barry. One reader was FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, whose agency opened a file on the paper after it ran “a full length photo of a nude male with a small American flag covering his pubic area,” in the words of an agency memo.

Peter would come into the office around 10 PM, and he would drop acid and get to work.

The office Novick joined was already a haven for runaways and dropouts, the District’s most notorious crash pad for the counterculture, where authorities came on periodic raids. There were no bosses, no salaries, no hierarchy. Ray Mungo of the Liberation News Service, an underground news wire with which the Free Press temporarily shared a rowhouse, recalled in his memoir raucous staff meetings that lasted “ten or twelve shouting hours.” Everything was subject to vote by the staff, whose ever-changing roster made each issue as one-of-a-kind as a homemade tie-dye. Besides Speltz—an ex-seminarian known for carrying out the city’s first interracial adoption—the staff included a Howard University dropout (cofounder Art Grosman); a former talk-show host who had fled Latin America after a drug-induced on-air meltdown; a Trotskyite; an ex–computer programmer from the State Department; and at least one defector from the Post. Novick fit right in.

Like every staffer, he did a little of everything—reporting, proofreading, taking ads over the phone. He also worked the streets, hawking papers at 20 cents each to cover his rent and food. (Staffers kept 100 percent of their sale proceeds—grassroots capitalism.) But even in an office defined by anarchy, his work habits stood out, especially on deadline. “Peter would come into the office around 10 pm, and he would drop acid and get to work,” says Speltz.

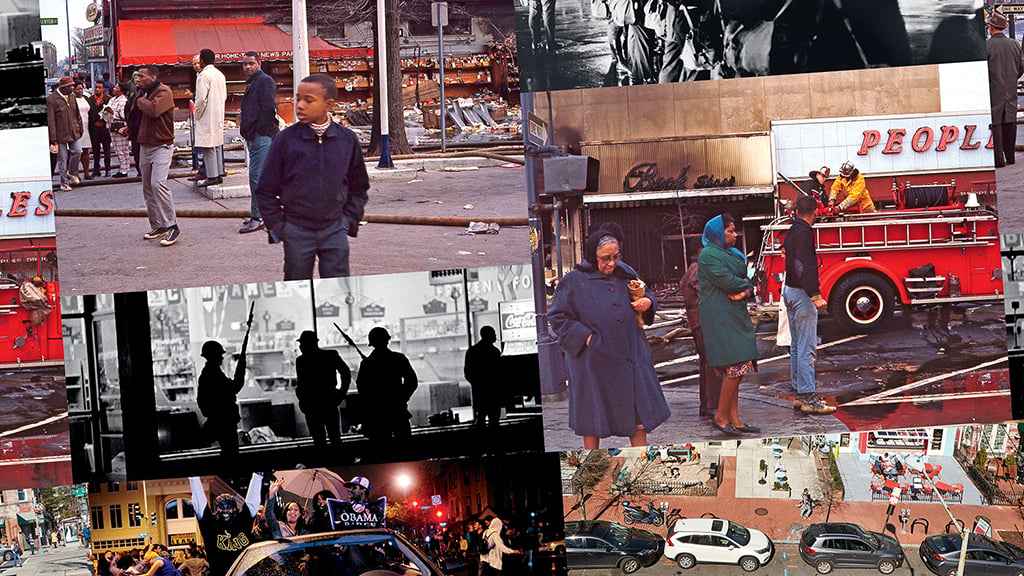

Novick interviewed the George Wallace for President campaign and the Scientologists at their Dupont Circle compound—“the only time I was ever scared,” he says. His eyewitness report on the ’68 riots was headlined with an incendiary quote from a police officer: “we’re gonna get every nigger and long-haired son-of-a-bitch.” (The officer, Novick reported, was enraged that his “favorite alcohol joint, the Ozark Club,” had been burned down.) Novick even wrote poems for the Children’s Page.

But above all, he became known for writing about drugs. In early 1968, he profiled the Neo-American Church, a group fighting for the right to use LSD as a sacrament, and one of its leaders, Judith “JD” Kuch, a psychedelic pixie with lsd25 on her red Volvo’s license plate. “But how can the Establishment cope with one whose ‘favorite fantasy is to walk down the street giving away free acid to the heads, flowers to the Georgetown ladies, candy and toys to the kids, winks to the young men, and smiles to everyone’? ” Novick wrote.

What goes unmentioned in the piece is that both were tripping during the interview. Novick took notes until the encounter went beyond the reach of language, he says: “It was one of the nicest experiences I ever had.”

Loose as he was about getting hopped up on the job, Novick was careful not to taint his own byline when he started his drug column: “I didn’t want readers to say, ‘Oh, he just writes about getting high.’ ” (There was also the practical matter of avoiding arrest.) Fooman was his bastardized shorthand for fumar—“to smoke” in Spanish. Zybar was the surname of a butcher with a handlebar mustache whose joyful mug was pictured on delivery trucks around Brooklyn, where his grandparents lived.

Novick envisioned his alter ego as a streetwise scientist in the worldly manner of Sherlock Holmes, investigating a different drug with each dispatch. One column celebrated the Hawaiian Rose Wood Seed, a sort of country cousin to LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline. He explained how to crush the seeds with a hammer and boil the powder into a tea that offered “a subtle trip that is truly of the highest essence of the psychedelics. . . . To obtain this gift from God, merely order them through seed distributors.”

He concluded: “Fooman did Rose Wood seeds every day throughout the months of October and November 1967, and most of December. . . . This is one that is definitely in the Must category.”

He was honest about the sordid details of his own bad trips, such as his maiden voyage on myristicin—a hallucinogen found in nutmeg—likening the taste to a urinal cake and the effects to a crippling lethargy that he rode out at an all-night cinema downtown.

Sometimes he could be a scold. Zybar warned a reader named Ed H. Jr. about the dangers of guzzling cough syrup (“A DM trip produces a drunken euphoria, hallucinations in vivid color and an incredibly bad breath. . . . [D]on’t do it more than once a year”) and lectured J.C. on the false allure of synthetic hash (“another episode in the never ending struggle by man to try to out-do nature”).

Not just the Ann Landers of Acid, F.Z. was also the Dr. Gridlock of the local drug trade, helping his readers navigate the dizzying array of highs and lows available on the streets. A 1968 column detailed the “latest figures for the dope scene in Washington. . . . Marijuana: A bit tight right now. . . . Nickel bags are a burn unless you know the cat and are a friend. . . . LSD: Yes, better and cheaper acid is coming. . . . Always cold shake, never heat LSD. . . . Psilocybin makes a groovy gift at Christmas time.”

He took every opportunity to rail against bureaucrats hooked on Reefer Madness–style crackdowns. “There is probably no other drug in popular use that has excited such unfounded hysteria, barbaric legislation, and wholesale distortions,” he wrote about the US’s war on weed while predicting a day when pot would finally become legal.

Over time, the office phone became a sort of bad-trip hotline. Whoever answered would hear loud music and hysterical screaming in the background as a frantic caller asked for Fooman Zybar. In some cases, trippers came by to drop off a stricken comrade. Novick “was a very kind person, dedicated and willing to give help to anybody in need,” says Speltz. “He was our gentle soul.” It wasn’t as if you could trust parents or doctors in those days. To whom could the heads turn except Fooman Zybar?

Novick came to think of his work as a sort of moral obligation. But while Fooman Zybar was warning readers that heroin was toxic, Pete Novick was embracing it, copping dollar hits on the street. One day in the early summer of ’69, Novick was in DC Superior Court, attending the criminal trial of a drug buddy, when a narcotics officer recognized him. Picked him up by the scruff of his neck and said, for all to hear, “Novick, I’m going to get you.”

It wasn’t long after that Novick was seen fleeing DC in his friend’s convertible, another junkie on the run. He says they did drugs all the way out west.

As it turned out, Novick couldn’t quit the newspaper business, either. When he landed in Fayetteville, Arkansas—a place he knew through friends—he moved into a one-room cabin and started the Ozark Mountain Times. It had the muckraking spirit of the Free Press but lasted only about a year, vanishing like so many other underground papers of the era. “They were like mushrooms,” he says. “They sprouted up overnight everywhere. And when their time had come, they were never seen again.”

That’s not quite the whole story, though. Novick was still an addict, and he had settled in a college town with a thriving hard-narcotics subculture. He had kicked heroin, only to fall under the spell of methamphetamines. He was busted again and pulled a stretch in an Arkansas state prison. Shaved head to toe, he worked in a chain gang clearing the sides of the highways with a hoe.

When he got out, Novick put his fascination with chemistry into something more productive: bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville. He ran a lab there and conducted research on pesticide residue, which included studying the urine samples of crop-dusters, who had bladder cancer at alarming rates. He was a workaholic—enthralled by the science. But he also took full advantage of his access to top-shelf lab equipment. On weekends, he’d make crystal meth for himself and his friends.

One Saturday while he was cooking a batch, an explosion rocked the lab and Novick rushed himself to the emergency room. “It almost killed me,” he says. “A button on my lab coat melted into my chest.”

By the early ’80s, better career prospects beckoned him back to DC. He was ready to grow up. Novick became a government contractor, writing technical reports about how chemical toxins affected the environment, and he also worked for a local lab. On Election Day 1992, he moved into his basement hideaway on the edge of Sligo Creek Park. He’s been there ever since.

Today Novick is retired and on disability. Many of the tenants, mostly immigrants, mistake him for the maintenance supervisor. “No one here can figure out who I am,” he says. “Do I run the place or am I some guy who just camps here?”

Novick, though, never gave up his penchant for lab experimentation—only now the schemes aren’t entirely about getting high. His subterranean locale gives him cover. One night, you might find him extracting gold residue from junked computer parts. On another, he might have returned from a friend’s property near Annapolis, hatching plans to process the seeds from a field of Queen Anne’s lace and sell the compound for research studies.

All those years of hard living have taken their toll. He has lung cancer (currently in remission), bone disease, and a transplanted liver. His recently diagnosed COPD requires portable oxygen tanks to help him breathe. “I was too reckless in my younger years,” he admits. Not that he has any regrets. Lenient marijuana laws in many states have vindicated Fooman Zybar.

Instead of recreation, most of the time Novick spends thinking about drugs these days is focused on scoring legal—and crucial—painkillers. He spends entire days on Metrobuses, seeing doctors and filling the Medicaid prescriptions that keep him alive against all odds.

These jaunts around town have actually sweetened him on the city that, as Zybar, he often lambasted. “DC was a dump back then,” he says. “The streets and alleys were strewn with garbage. The Potomac River was a cesspool. Georgetown had that [fat-rendering] factory, and people would be puking from the deepest muscles of their guts when that smell hit them.”

Every so often, a run-in from the past will remind him how once-in-a-lifetime it was to live through those Days of Rage. One time, he had to pay a traffic ticket at the Rockville police station and saw a court bailiff who looked familiar. “Is your name Peter Novick?” the deputy asked. “Did you work for the Washington Free Press?” It was the same narcotics officer who’d sent Fooman fleeing DC for his life that summer of ’69.

“The cop said, ‘Boy, those sure were crazy times, weren’t they?’ And he shook my hand like we were old pals. He had really mellowed out.”

If there’s a place in DC where it feels like the Free Press never died—nor, for that matter, the ’60s—it’s Art Grosman’s group house in Mount Pleasant. The Victorian-era farmhouse, under renovation for three decades running, is a pickers’ paradise crammed with memorabilia such as the paper’s first linotype machine (“Got it for $15,” says Grosman), Che-style murals, and dark and intensely personal paintings by a former Free Press contributor, John Fitzgerald. He was a rebel artiste from Suitland who one time in jail painted the cell walls with his own excrement and designed the first logo for the paper before, as legend has it, being killed in a Texas bar brawl.

Grosman, the paper’s cofounder, has long run a sort of crash pad for former staffers—Novick rented a room in the ’80s after his Arkansas sojourn. Now that the septuagenarian crew feels the other side calling, the home has become a gathering place for the old Freepers to have one last gas, too. “The Not the Taj Mahal,” as boarder Jim True, the paper’s graphic artist, calls it.

For the last several years, Novick and Grosman have spearheaded efforts to gather a full print run of the Free Press. It’s slow going, and several issues are still missing. Word is out to search basements and attics for fugitive copies that on eBay fetch $20 or more per issue. “It’s not easy to try to organize a bunch of anarchists,” Novick says. But with a little more effort, the near-complete run will have been donated to Dig DC, a digital archival project of the DC Public Library. After nearly 50 years lost down the memory hole, the renegade street rag will finally have a permanent home in cyberspace.

“Even though I’m the youngest of most of my friends, I figured I’d be the first to die,” Novick says. “So I thought I’d better do what I can now.” ’Course, it’s also nice to have an excuse to get together with old friends as a percolator of hot coffee and some freshly rolled reefer make the rounds.

That was the scene one cold morning last year as the men sat at the kitchen table inventorying a box of faded pages, Kinky Friedman blaring from a stereo upstairs. They reminisced about the March-on-the-Pentagon issue, laid out in a glorious all-nighter with the help of acid. They recalled alumni who had recently passed. Talk got around to all those unforgettable celebrities of DC’s long-ago counterculture, such as JD Kuch, the LSD-loving preacher.

Novick’s eyes brightened. He said that of all his interviews, the acid-enhanced encounter with Kuch was his favorite: “She could make you feel so good that you’d die with a smile on your face. She really believed in LSD, and I did, too. It was a philosophical approach. You wanted to have a religious experience. That was the goal, and most of the time it was profound and positive.”

The Freeps have remained news junkies, and the conversation turned to the opioid epidemic wiping out a generation of users still in their teens. Novick blamed blind ignorance on the part of users who have no clue what they’re taking. “We need someone like Fooman today to talk to these kids and educate them about this shit,” True said.

Not that Novick plans to resurrect his alter ego. The column ran its course, he says only half jokingly, when he ran out of drugs to write about. But he still loves to talk about what first got him into trouble with the law. After all this time, the powers that be have finally come around to Fooman’s way of thinking, so the Patrick Henry of Pot won’t have to look over his shoulder for the cops. He says he’ll soon have his Maryland medical-marijuana card.

This article appears in our August 2017 issue of Washingtonian.