One of the fall’s strangest art offerings is this collection of 19 creepy crime-scene dioramas, which were built to help budding forensic scientists learn how to solve cases. What exactly are these things? And what are they doing in an art museum? We asked Nora Atkinson, the Renwick’s curator of craft, to guide us through the grisly exhibit.

Who made them?

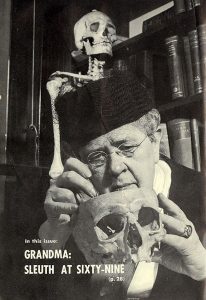

Frances Glessner Lee (1878-1962), an heir to the International Harvester fortune, was fascinated by the science of crime, but her family wouldn’t let her attend a university. Later, she used her wealth to endow Harvard’s department of legal medicine, which teaches forensic investigation, and in the early ‘40s she started building her dioramas as teaching tools. “You can see who she was through her craft,” says Atkinson. “She was using it in this subversive way to become part of a world that was off limits to her.”

How did she do it?

Lee scrutinized crime-scene photos and visited the morgue, working hard to nail true-to-death details such as blood spatter, lividity, bullet-hole placement, and rigor mortis. “Realism was at the forefront of her mind,” says Atkinson. “She was extremely serious about the scientific aspects being correct.” She also cared about less macabre details, crafting richly decorated domestic spaces to house the scenes.

But is it art?

Atkinson says Lee didn’t consider herself an artist, but her miniatures are clearly informed by her knowledge of domestic craft, which fits the Renwick’s mission. “There’s a lot of artistry in it. You start to see her creative tendencies emerge. It really does give you a key into her mind,” says the curator, who also notes a larger lesson in the works: “Her idea was to teach investigators how to really see. For us as a craft museum, teaching people how to see is very important.

“Murder is Her Hobby: Frances Glessner Lee and the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death” will show at the Renwick Gallery from October 20-January 28.

This article appears in the October 2017 issue of Washingtonian.