Over Christmas, a member of the British Royal family created an uproar for wearing a “blackamoor” brooch depicting a black person in a gold headdress when she met Prince Harry‘s biracial fiancée and actress Meghan Markle.

Here in Washington, Nicole Duncan and her husband followed the controversy. They hadn’t heard of blackamoor but started doing some research to learn why it can be considered racist and offensive. They discovered that this genre of art, which originated in Italy in the 17th century, often depicts very dark-skinned North African slaves and servants dressed up in jewels and fancy garments by European aristocrats trying to show off their wealth.

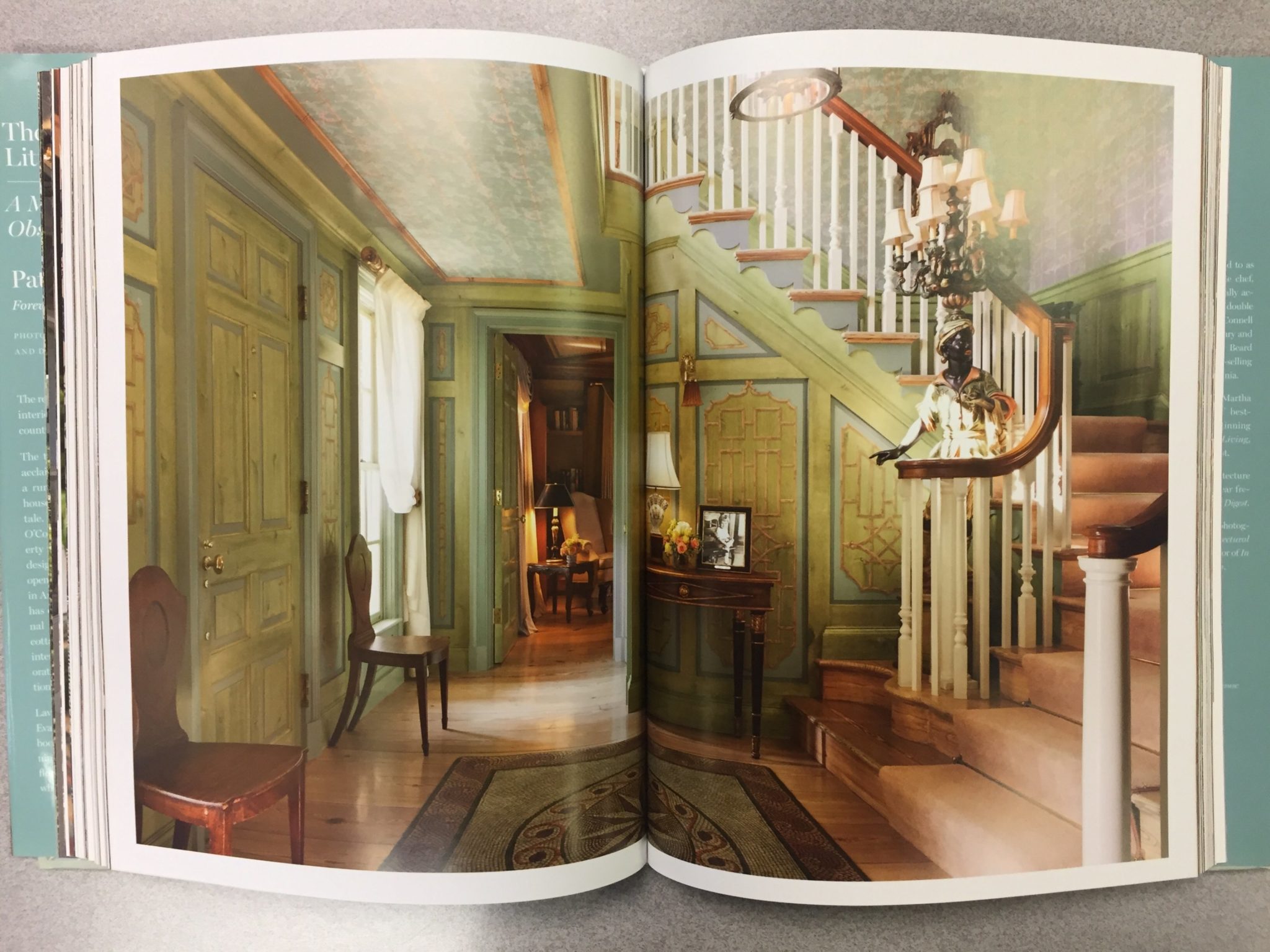

The couple realized they’d also seen blackamoor before—at the Inn at Little Washington.

In fact, the Michelin-starred restaurant has two blackamoor statues. The most visible one resides on a sideboard in the “living room,” where guests gather for afternoon tea or after-dinner brandy. Unlike other ornamental pieces in this style, which depict black bodies in positions of servitude (holding candelabras or bowls), this one is a Baroque-style bust draped in a gold robe and turban. In his book The Inn at Little Washington: A Magnificent Obsession, O’Connell says this “exotic blackamoor” came from the Virginia estate of socialite Patricia Kluge.

Not all blackamoor art is created equal, says Adrienne Childs, an independent scholar, art historian, and curator who has closely studied blackamoor. (The associate of Harvard University’s W.E.B. Du Bois Research Institute at the Hutchins Center is currently writing a book on the subject.) Yes, some fetishize slaves and servants, but others may depict black nobleman or generals. Still, the lines are blurred enough that the entire genre has become racially charged, especially in modern-day America. Several years ago, fashion house Dolce & Gabbana sparked outrage for including blackamoor earrings in its collection.

Childs has been to the Inn at Little Washington and seen the statue herself. She doesn’t think the blackamoor bust in the living room depicts a slave, but “it’s so fraught that I’m surprised that they left it in there in the United States of America in a place like this. There are many questions about it. You can look at it also and just see it as being another generic, exoticized, sort of orientalist image of a black person.”

Duncan and her husband are African-American and say they found the statue deeply offensive. Because they are devoted fans of Patrick O’Connell‘s whimsical fine-dining destination, they decided to call the chef to explain the historical context and voice their discomfort with the art. In their minds, it felt no different than a restaurant with swastikas on the wall.

Duncan’s husband, who wished not to be named, ended up speaking to Director of Dining Room Services Neil O’Heir.

“I said, ‘To me, it’s deeply, deeply degrading and belittling,'” recalls Duncan’s husband. He told O’Heir that he thought the statues should be removed. “‘I’m not going to be your customer, nor will I do any event there until they’re no longer there.'”

O’Heir promised to go back to O’Connell, explain their concerns, and call back, according to the couple. Duncan and her husband hoped to hear from the restaurateur himself, but instead O’Heir called back a week later. This time, they say he told them the restaurant would remove the statue—but only when Duncan and her husband visited. It would remain up otherwise.

“It could potentially be offending other people,” Duncan says, and not everyone may feel comfortable speaking up. “That they think that’s okay is really disturbing.”

That was more than a month and a half ago. Duncan and her husband have not heard anything since. After being contacted by Washingtonian, however, the Inn at Little Washington says it has decided remove the statue in the living room.

“For the last 40 years The Inn at Little Washington has succeeded in bringing its guests joy and pleasure,” says Director of Public Relations Annette Larkin in an emailed statement. “We are naturally saddened that an artwork of a handsome, Moorish nobleman which has rested on a sideboard at the Inn for more than two decades may now be perceived as offensive. Although only one party has objected to its presence in all these years, we feel the best course of action may be to grant the sculpture a leave of absence and remove it. We hope it can find a new home at the Metropolitan Museum of Art where a fascinating show is underway called: ‘Sculpture, Color, and the Body.’ We regret that any misunderstanding may have been created by the artworks presence here.”

As for the second statue? Larkin says it’s in a “private space.” Asked where that private space is and what the Inn planned to do with the second blackamoor statue, Larkin responded “a private space is one that is not open to the public. At this point we feel we have been more than accommodating.” She added they “consider the matter closed.”

In fact, that private space isn’t entirely private. It’s part of the Inn’s Claiborne House, named after famed restaurant critic and food journalist Craig Claiborne. In A Magnificent Obsession, O’Connell describes the house as “our ‘Presidential Suite.'” Over the years, Warren Beatty, Al and Tipper Gore, Alain Ducasse, and Michael J. Fox have all stayed there. The house also hosts weddings and events.

The blackamoor in the Claiborne House—holding a towel, with a candelabra on his head—represents what Childs calls “ornamental servitude” and “exoticized slavery.” She says this particular statue at the Inn is a 20th-century version of a tradition that became popular in 18th century, when fanciful images of subservient blacks were associated with wealth and luxury in Europe. “It is not an antique,” she says. “All the more reason to question why they put it there.”

Meanwhile, the Inn sent Washingtonian an article from an antiques website that disputes the notion that blackamoor art is problematic. “While some take offense at these pieces as degrading and racist, in fact the opposite is true,” the article reads. “The Venetians of the time employed these Northern Africans as servants and bodyguards and trusted heads of grand houses.”

But Childs says blackamoor art does in fact have clear ties to European slavery, even if some in the antiques world see such statues as cherished, regal figures. “Decorative art is insidious,” she says. “It naturalizes black slavery in ways that it makes people comfortable with it.”

For Duncan and her husband, removing one statue after inquiries from a reporter is too little too late. They say the Inn’s response doesn’t come across as genuine, and they question whether O’Connell understands the message the blackamoor statues send.

“They claim to be so customer-focused, but the customer was telling them about something, and they blew us off twice,” Duncan says.

The couple is further disheartened because they have been loyal customers for nearly five years. On their first visit, they coordinated with the restaurant to find out the gender of their unborn baby when they opened the dinner menu. They’ve spent thousands of dollars there since to celebrate special occasions and for VIP work events. They’d also planned to celebrate their tenth wedding anniversary at the Inn in November.

“I’ll never go back again,” Duncan’s husband says. “And I love the place.”