When The McLaughlin Group hit airwaves in 1982, the notion that this syndicated current-events show might become an institution would have horrified most media observers. The program’s then-unusual format—a bunch of pundits sitting around a table arguing with each other—offended the sensibilities of the establishment political class, with the Washington Post calling it “public affairs television for an MTV era” and the New York Times predicting that it would make other opinion pros “weep at the loss of any last shred of political gentility.” Even Mad magazine sniffed that it crammed “two hours of commentary into 30 minutes by having four people talk at the same time.”

Whatever, haters: McLaughlin grew into such a phenomenon that it earned a recurring parody on Saturday Night Live, and host John McLaughlin even showed up on the sitcom ALF. Though ratings eventually flagged, the show kept going right up until McLaughlin died in 2016. At that point, its run came to an end. Or so everyone thought. Now, like some terrifying creature from The Walking Dead, The McLaughlin Group is back.

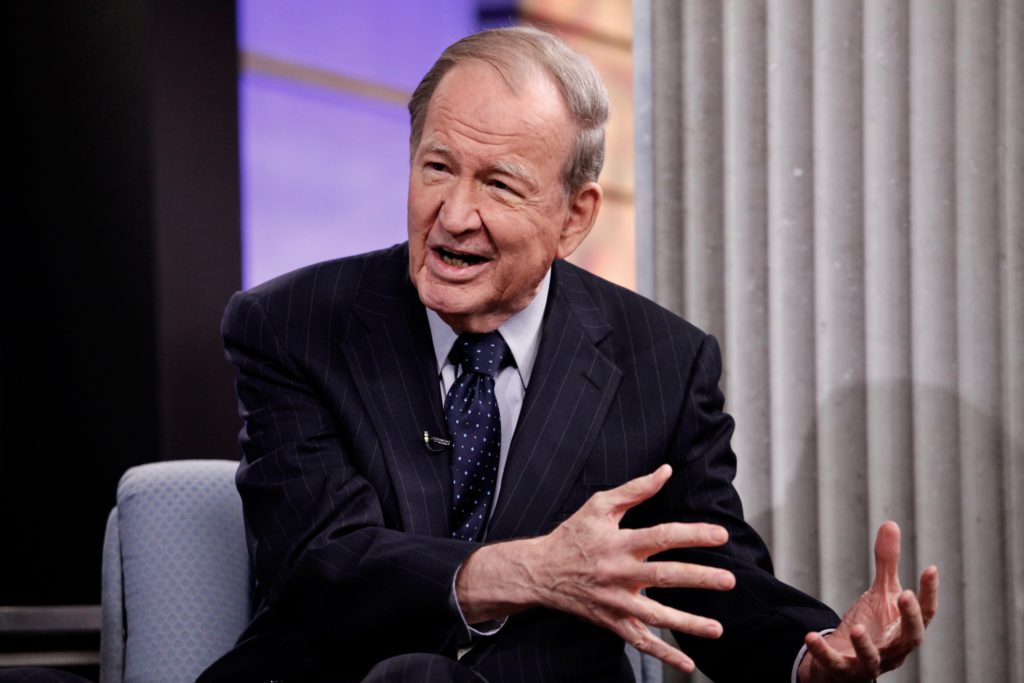

At an Arlington TV studio early on a recent Saturday morning, the new show’s lineup of pundits—all veterans of the original—had gathered to tape an episode. Soon enough, they were arguing at impressive volume. Eleanor Clift, now a columnist for the Daily Beast, vehemently disagreed with Pat Buchanan about the Robert Mueller investigation, while the Chicago Tribune’s Clarence Page referred to the Russians as “Soviets.”

The only thing missing was, of course, McLaughlin. This new version—which right now airs only on WJLA and YouTube—is hosted by a guy named Tom Rogan, who on this particular morning was struggling to maintain McLaughlin’s level of authority over the proceedings. In the booth, the audio feed started pushing into the red as Rogan tried to get a word in. “I’m the commander!” he finally shouted. Everyone just kept talking.

TV news has changed dramatically since the ’80s, and McLaughlin’s innovations have since become the news-channel standard: people with wildly divergent opinions talking past one another while making often-inaccurate predictions. It would be easy to argue that the program’s moment has long passed. But the show is making a contrarian argument: It wants to be an antidote to all the cable-news shouting it helped inspire.

By the time Rogan arrived in Washington in 2012, neither McLaughlin nor his show was in the best condition. But that didn’t deter the budding journalist, who had grown up in Britain, the son of an American father and a British mom. In DC, he craved a career as the sort of writer who regularly appears on television. While still a freelancer for various outlets, he began pestering the show’s producers to let him on the panel. McLaughlin gave him a shot as a guest panelist in August 2014, and after that appearance the two developed a mentor/mentee relationship. Rogan became a regular, and he says they even discussed his hosting a millennial-oriented spinoff. All of that ended when McLaughlin succumbed to complications from prostate cancer.

Since then, Rogan, an impressively under-shaven and rumpled 32-year-old, has maintained a typical DC-millennial existence. He lives in a group house in Ballston with his brother and works as a columnist at the Washington Examiner.

The McLaughlin chapter of Rogan’s story might have drifted down his LinkedIn page had longtime panelist Clift not run into a McLean lawyer named Seth Berenzweig in March 2017 at a DC beer garden. Berenzweig, a smooth-talking guy who does legal analysis for WJLA on the side, introduced himself to Clift, and they kept in touch. She, Rogan, Buchanan, and Page had been talking about whether they could somehow bring the show back. Clift thought Berenzweig could help.

She was right. The lawyer ended up negotiating a deal with the McLaughlin estate not just for the program’s title but also for its ’80s-health-club-style graphics, bombastic theme music, and laminated furniture. He even got the mugs.

WJLA’s owner, Maryland-based Sinclair Broadcast Group, signed on to air it in 2017. The next question was who would take over the big man’s center seat. The youthful Rogan seemed like a good pick. “He comes across as an innately decent guy,” Clift says (perhaps an odd qualification for replacing McLaughlin, who was famous for bellowing “WRONG!” at other panelists). In addition to regulars Clift, Page, and Buchanan, a final seat is filled by a rotating cast of yakkers, including Evan McMullin, Bill Press, and, on the morning I visited, Kelsey Harkness from the Daily Signal.

The format is pretty much the same. The tone, however, is supposed to be more civil—a deliberate strategy meant to distinguish the new Group. “We used to be considered part of the problem,” Clift says. “I now see us as part of the solution. I like to think that we go beyond the talking points so it’s a level of discussion that’s meatier than in the cable shows.”

So far, it isn’t always working out that way. The panelists have developed their debate style over the course of decades, and change isn’t coming easy. At one point during my visit, Rogan grew frustrated with the heated cross-talk. “Enough! Enough! Enough!” he cried, shutting down the shouting and going to commercial.

At other times, the panel does seem to be making an effort, handling frequent disagreements in respectful tones. Clift and Buchanan occasionally find areas of accord, and Page manages to sound bemused more than appalled while discussing Trump. During commercial breaks, the conversation continues—a sign that perhaps they do enjoy one another’s company.

Rogan, meanwhile, is still learning how to run things. “What I need to do more is stamp my foot down, take more control when it is necessary,” he says. But he doesn’t plan to adopt his predecessor’s trademarks, such as ending the show with that slightly goofy “bye-bye.”

“I think if I tried to render myself a carbon copy of McLaughlin, it would be a terrible mistake,” he says. “Because no one can be him.” The question now is whether Rogan and his new Group can truly become something else.

This article appeared in the April 2018 issue of Washingtonian.