Trevor Paglen grew up seeing the US differently from the way many Americans do. He was born on Andrews Air Force Base and raised on military bases across the world, an experience he says helped him understand a “greater American geography.”

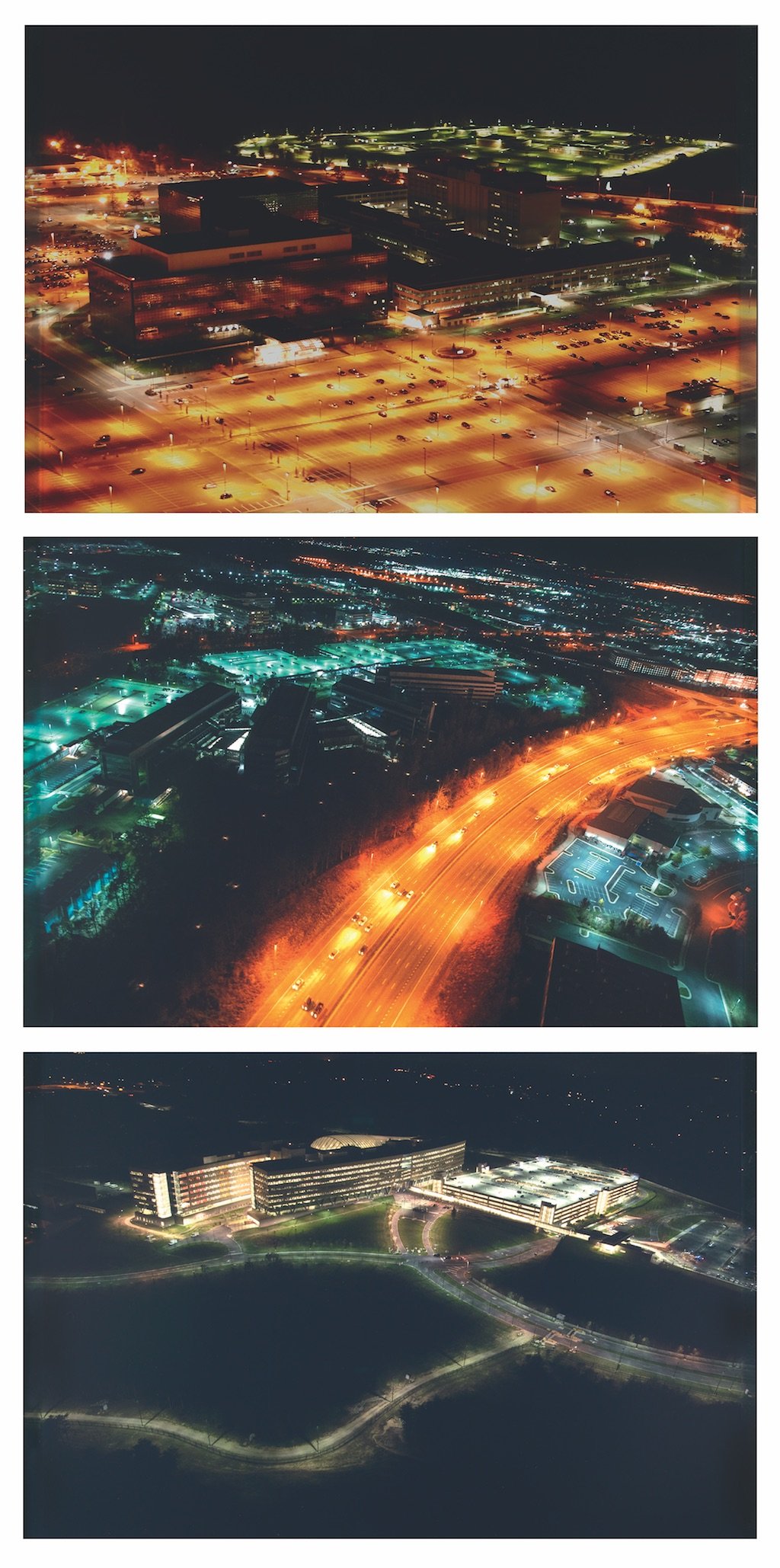

Paglen’s photographs, videos and sculptures focus on the secret institutions that surveil and shape our lives, as well as the symbols they use to communicate what “must not be communicated.” His new show at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Sites Unseen, brings together over a hundred works that ask questions about the technologies we’ve invited into our lives—from spy satellites to artificial intelligence—and who’s really calling the shots.

Washingtonian sat down with Paglen to discuss the exhibition’s on-the-nose location, how we see, and how machines see us.

Washingtonian: What’s it like to have this show in one of the major global hubs of military and government surveillance?

Trevor Paglen: It’s fantastic! It’s fantastic. First of all, it’s a public museum, and I really am a fan of civic institutions and public institutions. Creating places for ourselves where we can reflect on things, to me, seems like a really important thing to have in any society, and so that’s a great honor to be able to work with one of the major public institutions in the country. It’s also fun because a lot of the things that I look at—there are a disproportionate number of people in the area who are either touched by the kinds of things I look at, or involved in the kinds of things that I look at, whether that is technology or it’s military things or intelligence things. And so it’s fun to have that kind of audience, where you can have more complex takes on it, and an audience that has a series of more complicated relations to it—and more direct relationships to it—than you might find in some other places.

So much technological advancement comes from military applications and innovations. Do you feel like you’re using the surveillance state’s tools to surveil it?

I actually don’t think so, when you think about what those tools are. I can build a neural network that has roughly the same architecture as a neural network that Google would build, for example. But I don’t have a planetary-scale infrastructure that’s capable of sucking up that vast amount of data, you know? I have a guy and a computer in a room. So while it may appear that those technologies are the same, when you look at their actual footprint and how they function, they’re completely different and have very little to do with each other. It’s the difference between having a tricycle versus a giant monster truck.

So much of this exhibition is about ways of seeing. How do you think the state sees us?

Many, many different ways. I don’t think of the state as being an internally homogeneous entity with a singular way of seeing. One of the tendencies that you see with technology becoming more and more ubiquitous, and sensing systems and imaging systems becoming more ubiquitous, is a tendency to quantify things. In other words, only things that are quantifiable become intelligible to institutions. On the other hand, I think you see a kind of consolidation of power in fewer and fewer loci—an NSA or a military, or a Google or a Facebook.

So are we finding new ways to quantify?

Yes and no. I think there are new things that are trying to be quantified, but I think that often has bad consequences. In the video installation Image Operations, there’s a whole host of computer vision algorithms analyzing the performance of a string quartet. One of the things that happens over the course of the video is there are some computer vision algorithms that are trying to figure out what gender the performers are. It’ll say, “Okay, I’m looking at this face, and I think this face is 67 percent female or 45 percent male,” or whatever it is. When you think about it a little bit harder, you think “Well, that means that somebody has decided that there’s something such as 100 percent female and 100 percent male.” And who’s made that decision? Based on what kind of criteria? What does that quantification do? And I think obviously there’s some kind of bias built into that way of seeing itself, taking a particular way of seeing and generalizing it. On one hand, there’s this question of bias and fairness, and there’s also a question about this consolidation of power—who gets to decide who’s a woman and who’s a man?

A lot of the exhibition text refers to legal means of acquisition—of photographs, of objects. How much does staying on the right side of the law matter, both in your practice and personally?

A great deal. I’m very conscious about not breaking the law, but also insisting on my rights. In the US, you actually don’t have to break the law to make the kind of images that I’m making. The US is a very paradoxical place in that on one hand, we have enormous infrastructures that operate in secret and exert enormous influences over society, but at the same time, we are also living in one of the most open societies that’s ever existed on the planet. Taking advantage of that is a big part of what I do.

Sites Unseen opens Friday, June 21 and runs through January 6, 2019 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, on the corner of 8th and F Streets. Gallery hours are 11:30 AM to 7 PM daily.

This interview has been edited and condensed.