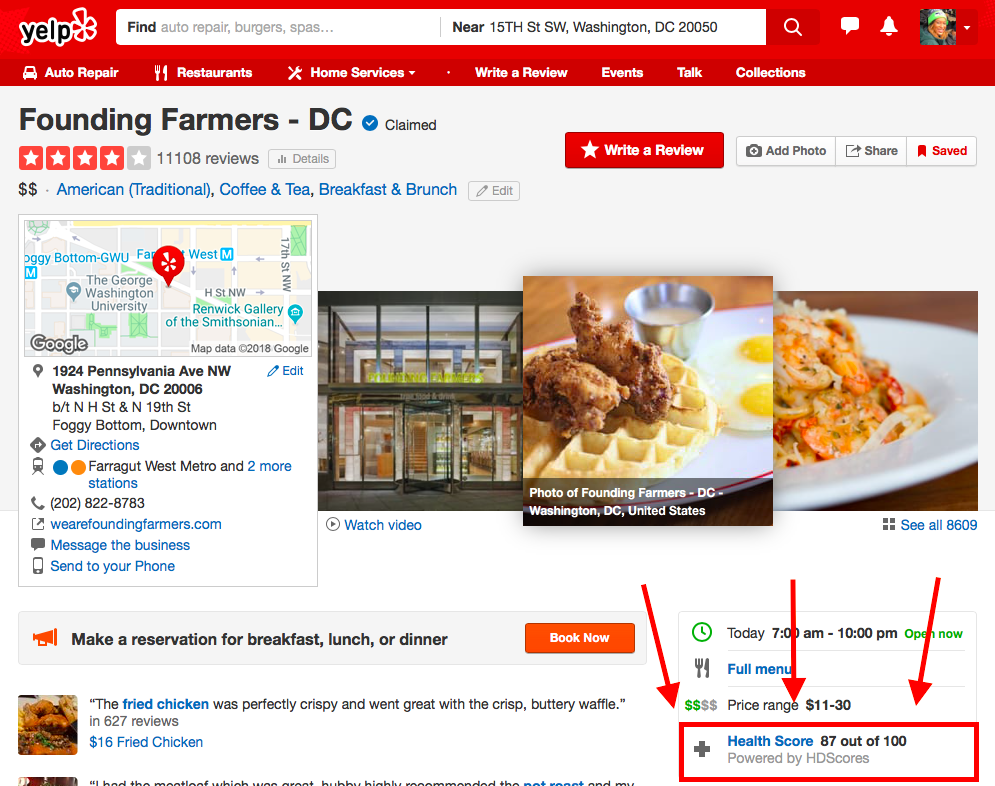

Yelp is no longer just for complaining about empty water glasses and sharing blurry photos of half-eaten burgers. Now, you can look up health inspection scores for DC restaurants.

The consumer review site began posting health inspection information in select cities five years ago, and expanded the feature to more than 350,000 restaurants across the country as of today. In the coming months, they’ll roll it out in even more states, including Maryland and Virginia.

Yelp partners with a Baltimore-based company called HDScores to rate restaurants from zero to 100 based on the official health inspection reports from local jurisdictions. The hitch? The DC health department doesn’t actually use a 100 point system. Rather, it employs a pass/fail method and divides violations into categories labeled “priority,” “priority foundation,” and “core,” which are difficult for the average diner to decode.

“It’s this totally esoteric thing that means something to an environmental health inspector who’s trained to do that job,” says Luther Lowe, Yelp’s SVP of Public Policy. “It means something to the restaurateur. Who are we leaving out of the equation? This is not a user-friendly signal for diners.”

Lowe says Yelp and HDScores did not consult with the DC Department of Health on how to translate its reports to the 100-point system, but it does have its own team of experts in the field. DOH representatives declined to comment on Yelp’s new feature.

Lowe hopes that rollout spurs cities and counties to provide more user-friendly health inspection data going forward. “We just made a decision we’re not going to wait for that to happen,” he says.

HDScores Chief Technology Officer Andy Phillips says they calculate their score based on the number of demerits on an inspection report, the severity of the violations, and whether those issues are corrected on site. More recent inspections hold greater weight. “From a translation standpoint, I’d like to think that we actually add clarity to it,” he says.

Yelp doesn’t give any official guidance on what a “good” or “passing” score is. Lowe says users will have to make that decision for themselves. “The zero to 100 system is something that virtually all Americans are familiar with. It’s what we use in grade school to size us up,” Lowe says. “If a user sees that a restaurant has something higher than an 80 or so, they probably can feel relatively confident that they’re going into a restaurant that’s not going to make them sick.”

The Yelp reports show the general type of violation a restaurant received, but not specifically what the violation was. For example, Yelp will tell you that Fig & Olive received a “critical violation” regarding insects, rodents, and animals on its June 19 report this year, but it doesn’t tell you one, like the DC health report does, that inspectors observed one dead German cockroach in the washing area or a “moderate amount” of gnats around the kitchen and bar. In the not-too-distant future, though, Yelp will likely link directly to the official reports.

The scores are based on data from the past two years, but only the most recent inspections appear on Yelp. (New ones will be added going forward.) That means, for example, you won’t see anything about Fig & Olive’s infamous salmonella outbreak in 2015.

The health score page on Yelp also asks users to “report any health complaints about this business such as potential food borne illnesses,” but provides an email to HDScores rather than the DC health department. Lowe says user complaints are not used to calculate health scores, and that HDScores plans to pass on health complaints to health officials.

But reps for HDScores say that’s not quite right. They want users to contact them about data problems, but they would defer people with actual health concerns to the appropriate authorities.

“We should probably separate the two,” Phillips says. “Contact local jurisdictions for any food borne illnesses.”