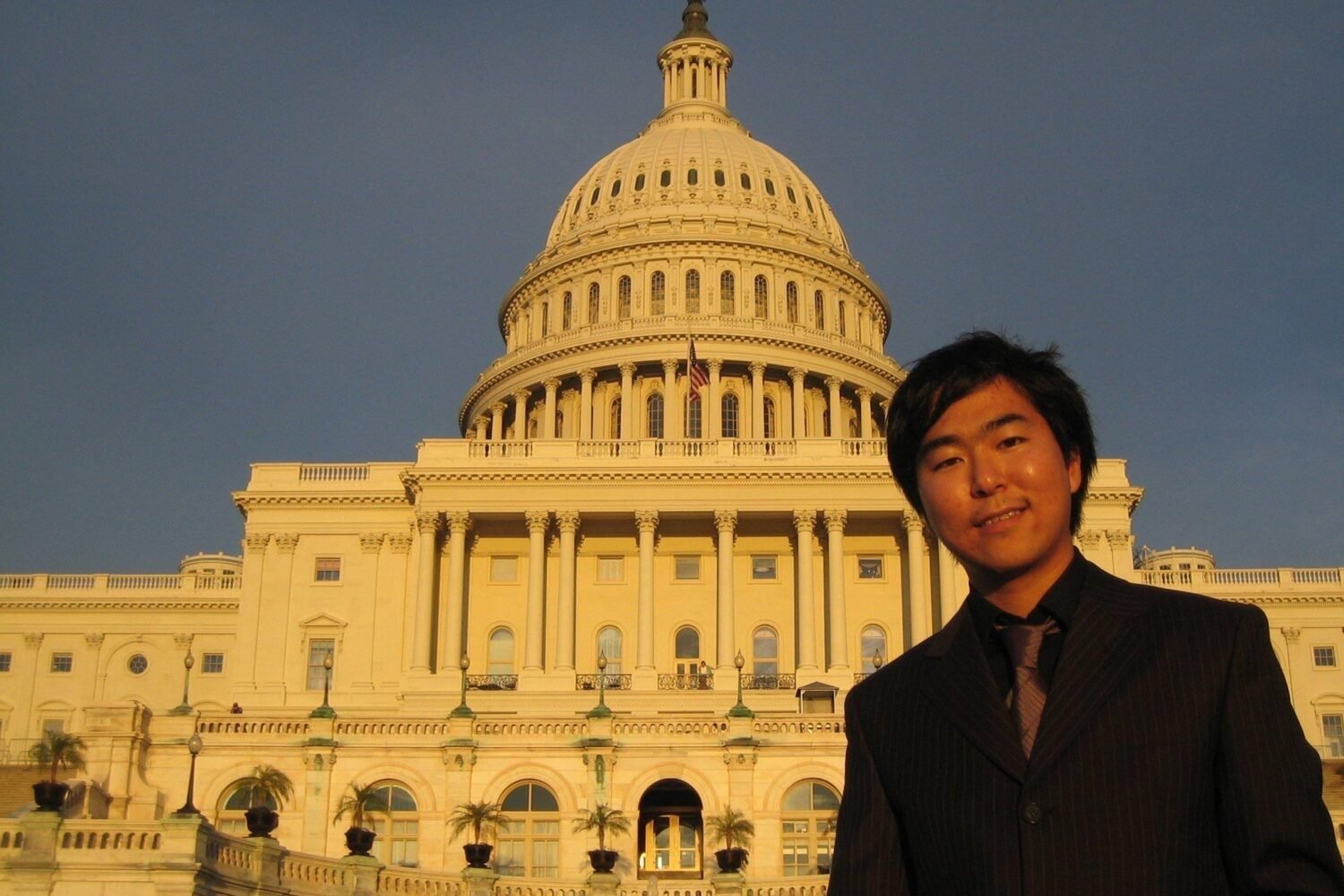

When Mohamed Younis was selected to replace Frank Newport as editor in chief of Gallup, the 38-year-old became the first millennial to lead America’s oldest legacy polling firm. Trained as a lawyer, he’ll helm an organization that, while perhaps best known for tracking presidential job-approval numbers, actually offers a broad range of public-opinion and analytics services.

Younis, who emigrated to the United States with his family in 1982, takes charge during one of the most turbulent political moments in American history—a fact illustrated by the record-length government shutdown that was still ongoing when he spoke to us during his first month on the job.

Over the course of an hour, Younis, who joined Gallup as a senior analyst in 2009, discussed the challenge of accurate polling, being a first-generation immigrant, and what living abroad taught him about studying public opinion.

There’s a lot of debate now about the quality of polling. A white paper, “The Gallup Poll and Some of Its Problems,” discusses researchers who surveyed American households on which brands of custard and other desserts they owned. They concluded that the only way to eliminate all error would be, theoretically, to walk into the house and check the cupboard. It was written in 1954—which makes me wonder how much of polling’s problems are really new.

If you really want to go out there and capture what’s happening with people in an accurate and valid way, people’s behavior is always changing. [Gallup Poll founder] George Gallup became famous because he was essentially willing to do things differently than what others were doing at the time. A lot of people were saying we had reached the end of public-opinion polling—in 1948!

When Dewey “beat” Truman.

Imagine! And a lot of polling organizations tweedled out at that time. But Gallup doubled down and figured out why it was wrong and reminded everyone what a margin of error is—that this is a probability study. From then on, he just continued to be absolutely committed to testing his methods and improving them. Like the custard problem: That’s an issue that really exists. People’s perceptions are never going to line up with reality.

You’re talking about misperceptions. In a Gallup Poll, Americans now view immigration as one of the most important national problems. But if all you had were the underlying facts about 2019—strong economy, declining illegal immigration over the last decade, the country’s record diversity—could you ever have predicted that immigration would be the preoccupation?

Because I’m a Muslim American, it’s not unique to find the work I’m doing connected to the national conversation.

We’re not going to predict what’s going to happen in ten years. We’re not in the business of doing that. When we look at trends, what we’re trying to understand is: What are the critical trends we should follow if something is shifting in society? It’s not with the objective of predicting an outcome.

I want to go back to [the point about] George Gallup and predicting presidential elections. What we want to understand is: What are those critical indicators? What we’ve learned is that those indicators change over time, and obviously a very ABC thing for any polling organization is that you absolutely have to constantly reexamine the questions you’re asking. In other words, there are ways to ask about the custard that aren’t directly about the custard, which you can glean from other answers in a survey on an issue. We do that all the time.

You’re the first millennial to run Gallup. What are some issues you’re attuned to that are distinctly generational?

Something that’s definitely changing is what’s happening on social media. We did a study with the Knight Foundation that’s focused on what’s happening on university campuses. One of the things we found is that with some respondents, social media is having a chilling effect on their willingness to participate in political discourse and discussion online. That was a little counterintuitive to those of us who have been cheering social media. Some of us viewed it as the great liberator. But that’s really changing.

And income disparity. One of the things that have surprised me recently in the work we’ve done is that 62 percent of Americans think they want Congress to focus on this as an issue. What’s that about? And who are the folks being impacted by that? What are the solutions people see as potentially taking place? Are people’s attitudes about what government should be doing going to change? What does that look like and how does technology change people’s concept of small or big government? Those are the issues we’ll continue to follow.

Your predecessor, Frank Newport, was famously inscrutable about his political views. But you’re from an immigrant Muslim family, studying American views at a time when those identities are often vilified. Our politics are perhaps the most polarized since the Civil War. What’s your approach to staying politically neutral?

Because I’m a Muslim American, it’s not particularly unique to find the work I’m doing connected in some way to the national conversation. One of the first things I did when I came to Gallup was work on a team focused on understanding relations and perceptions between Muslim-majority societies and non-Muslim-majority societies. So actually, since day one here, I’ve been tasked with looking at data that touch upon issues I have a personal connection to.

On the challenge you mentioned—polarization—I really view that not necessarily as a challenge but as our greatest calling at Gallup. Our founder and the many people who have carried on the legacy, generation after generation, have viewed ourselves as a trusted voice on what’s happening with Americans. An increasing challenge, working on any social science, is that the conversation has become much more antagonistic. It’s been happening for a long time, not just since the election. It’s a challenge really all of us face.

What about your family’s journey to the US? Has that influenced your perspective?

I was born in Kuwait, moved to Los Angeles when I was a few months old, and grew up in LA. Then I moved with my mom and my brother to Cairo for three years [when I was nine]; then Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for three years; and then back to Southern California.

I got to live in three countries in five years, between the ages of nine and 13. That experience was extremely eye-opening. One thing I learned at that age was that people have a lot more in common than they have differences. Despite languages or geographies or economies, there’s a lot of common ground between people that’s often lost because they really don’t have the opportunity to understand what people on the other side are thinking or doing.

At a very young age, that kind of captivated me and concerned me at the same time. But also it instilled in me a responsibility to try to connect the dots, in my own mind as an analyst, to understand on a deeper level what we have in common, what’s not in common, and why that is. Everything sort of starts from there.

This article appears in the March 2019 issue of Washingtonian.