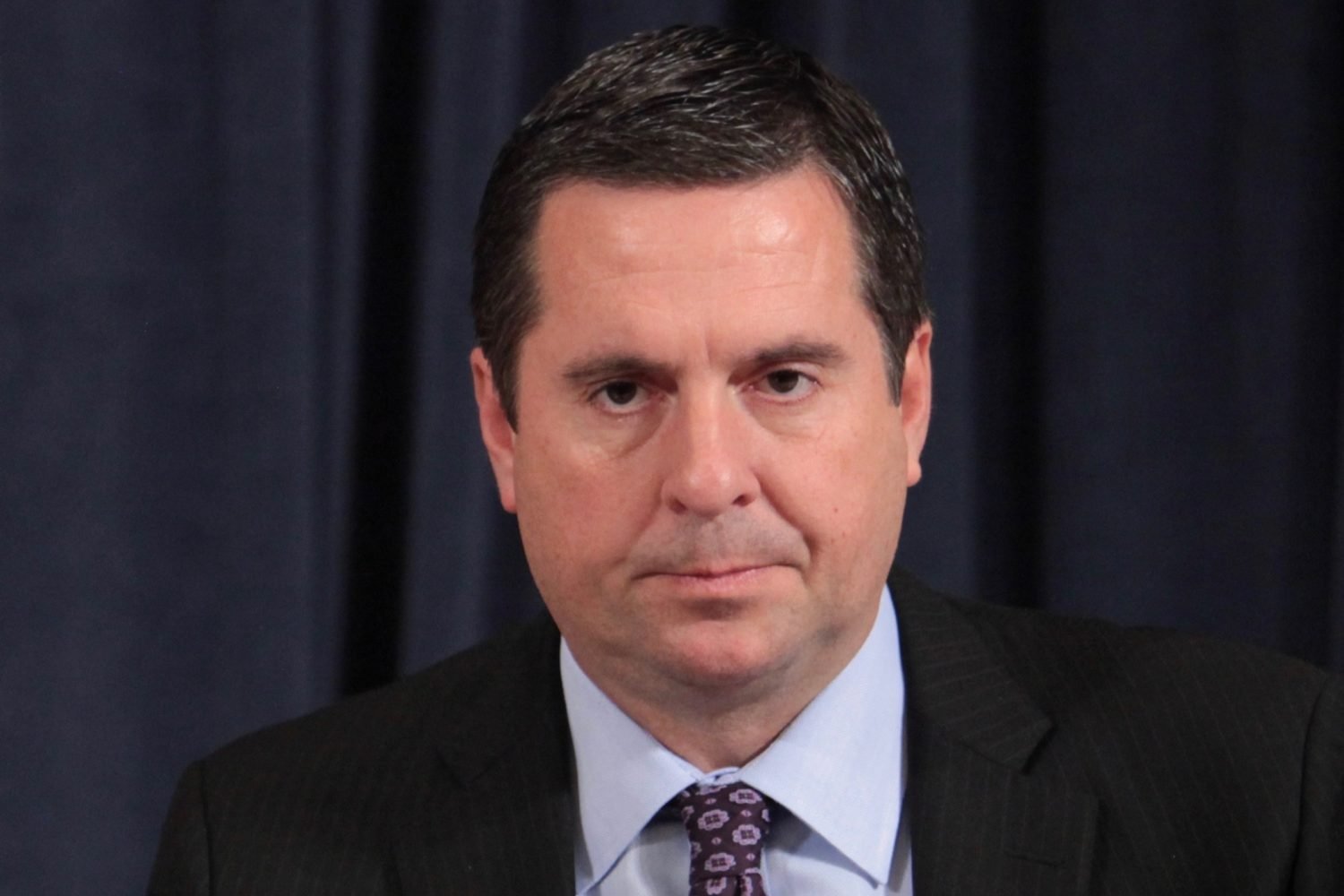

US Representative Devin Nunes filed a lawsuit Tuesday against Twitter, Republican strategist Liz Mair, and two parody Twitter accounts—@DevinNunesMom (now inactive) and @DevinCow—for defamation. While many laughed the congressman off the internet, others, like the Washington Post‘s Aaron Blake, worry the suit could have a troubling impact on political discourse. We asked Georgetown Law professor Anupam Chander if the Congressman actually has a case.

Is Nunes’ suit against Twitter serious?

Only to the extent that it kind of shows that some politicians can’t take either a joke. I think it reveals more about the plaintiff than it does about the actions the plaintiff is complaining about.

Can people really sure a platform like Twitter over accounts like the ones Nunes is targeting?

No, people cannot sue Twitter because it hosts a parody account that makes fun of a congressman. Twitter is protected by the Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. It’s not liable for the fact that someone is going to use Twitter’s service to say something rude about the other side. That is par for the course for Twitter use.

Even without Section 230 I don’t think that there would be any lawsuit that would fly against Twitter. Twitter is not actively developing or stoking negative feelings about Congressman Nunes; it’s simply allowing people to say things, sometimes in a funny way.

Is Twitter different in legal terms than the New York Times or a publication?

Twitter is not held to the editorial standards of the New York Times. The New York Times is held responsible for the stuff that it publishes…but in this case they would not be liable for running an ad with Devin Nunes’ cow or mom poking fun at him. They have the First Amendment, and Twitter has both the First Amendment and Section 230, to be specific.

Clarence Thomas mused about New York Times v. Sullivan being wrongly decided. That’s the precedent that makes it hard for public figures to claim libel. Is that standard in danger?

I don’t think so. This is free-speech court. I haven’t followed Justice Thomas’s view on the subject but this [Supreme] Court has been more zealous about protecting free speech than any Court in history.

Nunes claimed that the tweets criticizing him are an “orchestrated effort,” that people are “targeting” him. If this were true, could he have a case?

If he could prove that Twitter was actively helping draft these tweets, then yes, he would have a claim. Section 230 doesn’t protect you if you wrote the stuff. It protects you if other people wrote it.

What kind of precedent could this set?

I suspect it will be thrown out in a hurry, and will further demonstrate that politicians can’t simply go after internet platforms whenever they’re displeased when someone uses the platform to criticize them.

Even if Twitter were actually “shadow-banning” conservatives, is that illegal?

That would be legal. There’s nothing that says that a platform has to be an open forum for everyone to speak. It bans a lot of things already, some of which is on the basis of politics, so I think that that would not change. And it doesn’t shadow-ban conservatives! But if that were true it would still be immune.

What kind of evidence would someone look for in demonstrating actual malice or reckless disregard on the part of a Twitter account?

One could imagine a scenario where a person is actually engaged in impersonation rather than parody, where the person is pretending to be someone other than who he or she actually is. And there are a number of cases on the internet where people pretend to be someone else, and those people aren’t protected because they’re essentially carrying out a form of identity fraud. But that’s not happening here, as far as I can tell.

How would you go about defending a case like this if you are Twitter?

You cite cases like Hustler Magazine, Inc. v Falwell, which was a case where Jerry Falwell sued Hustler for publishing parodies of him and the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Hustler. And you cite Section 230, which offers a broad immunity for these kinds of claims. You can also test the factually incorrect claim that Twitter developed this content, and you state clearly that Twitter did not write, edit, or ask Devin Nunes’ mom, the owner of that account, to write this material.