One day in 1951, a young Washington activist named Harris Wofford and Ram Manohar Lohia, an apostle of Mohandas Gandhi, arrived at Princeton University to pay a visit to Albert Einstein. Wofford had met Lohia on a trip through India and, enraptured by the Indian activist’s entreaties on civil disobedience, arranged to give him a tour of the US.

On their six-week travels, Lohia saw the American South and the intractable problem that Wofford would later write “lays bare the secret heart of America”—white racism. Twice, police removed Lohia from diners. In Tennessee, the pair visited a training ground for activists, whose instructors Lohia convinced to add civil disobedience to their curriculum—where it was later taken up by a young student named Rosa Parks.

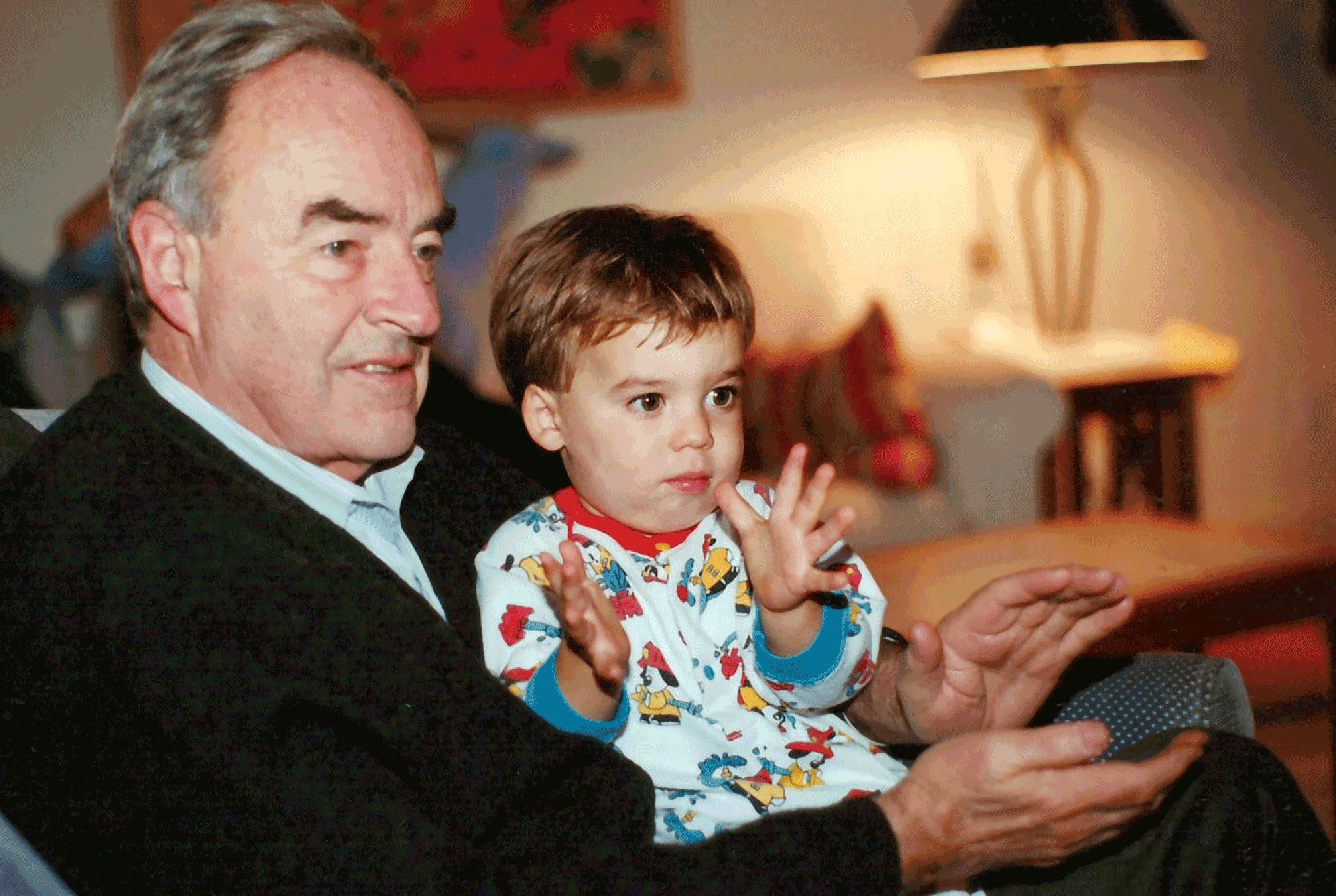

Wofford, who died this year at 92, was my grandfather. Over eight decades in politics and letters, he carved a reputation as one of his generation’s oddest figures. A flair for serendipity put him beside some of the century’s most inspiring figures: adviser to Father Theodore Hesburgh on the US Commission on Civil Rights, lawyer to Martin Luther King Jr. (who joked that Wofford got him into jail instead of out), aide to Jack and Bobby Kennedy, confederate of the Clintons and Obamas.

This uncanny arc includes an upset Senate victory in 1991, which elevated universal health care to national politics. (“Health care as a right? You know who started that line of thinking? A guy named Harris Wofford!” Rush Limbaugh once barked.) “Pick pretty much any other major chapter from the last 80 or so years,” Jason Zengerle wrote in the New Republic, “and there’s a shockingly good chance that Wofford played a role.”

Papa Harris delighted in recounting these tales. (“I can stand another speech,” my grandmother, Clare, complained, “but only if I hear one new story!”) He was often feted as a visionary. Our family, of course, knew the private dimensions that lay (endearingly, infuriatingly) at his core: Eternal optimism. The march of big ideas. “Remember,” he loved to say—his maxim for life—“it’s sooner than you think.”

He was also generous beyond measure, taking four grandsons on a trip around the world. I remember the night in Beijing when he recounted how Bill Clinton had called Clare, who lay terminally ill in the hospital. She smiled faintly as her husband held the receiver to her ear. The next morning, he threw open the blinds and announced, “Let there be light. It’s the kind of cold, sunny day, with the world covered with snow, you most like,” then turned to find she was gone.

I didn’t know at the time he shared this memory that he’d begun a relationship with a man, and when he embraced this new chapter, marrying Matthew in 2016, he kept stride with his love of the heterodox and his aversion to ideology: He announced his wedding, at age 90, in an essay for the New York Times—in which he quoted philosopher Martin Buber—while refusing to identify as gay.

At the end of his life, my grandfather did manage to tell us a new story: his trip to Einstein’s doorstep. He looked on while the Nobelist and the Indian activist passed the afternoon discussing politics and philosophy. Before they left, Einstein tugged on Lohia’s sleeve. “It’s wonderful to meet a great mind,” he murmured. “One gets so lonely.”

As my grandfather’s days dwindled, he retold the story. “One gets so lonely,” he repeated, over and over. He died acutely aware that the country had repudiated his core beliefs; I wish he might have lived to see us rededicated to them. But I wonder whether there’s still room for his optimism: the faith that we can afford to be generous in politics, that big ideas will prevail. The belief that for this country, at least, it may be—however improbably—still sooner than we think.

This article appears in the May 2019 issue of Washingtonian.