There are two net motions that are excellent for catching butterflies. One is the drop, where you quickly lower your net over an unsuspecting butterfly so it looks like it’s unexpectedly found itself on a camping trip. The other is a snappy figure-eight motion, which Smithsonian horticulturalist Sylvia Schmeichel demonstrates for me as cars whiz by below her on the 12th Street Expressway. You approach the butterfly from the side, then whip the net around twice so that the insect is good and caught.

It’s a beautiful sunny day in late October, and Schmeichel and plant-health specialist Holly Walker are patrolling the Mall, looking for monarch butterflies to tag. Both scientists work for Smithsonian Gardens, the “museum without walls” all around the Smithsonian’s museums. The first butterfly we catch is a male. “Excellent!” says Walker. You can tell by the tiny black scent glands on the monarch’s wings. Schmeichel grips the butterfly firmly and gently. Then she takes a numbered sticker and place it over the discal cell, a sort-of Michigan-shaped orange field on the butterfly’s outside wing.

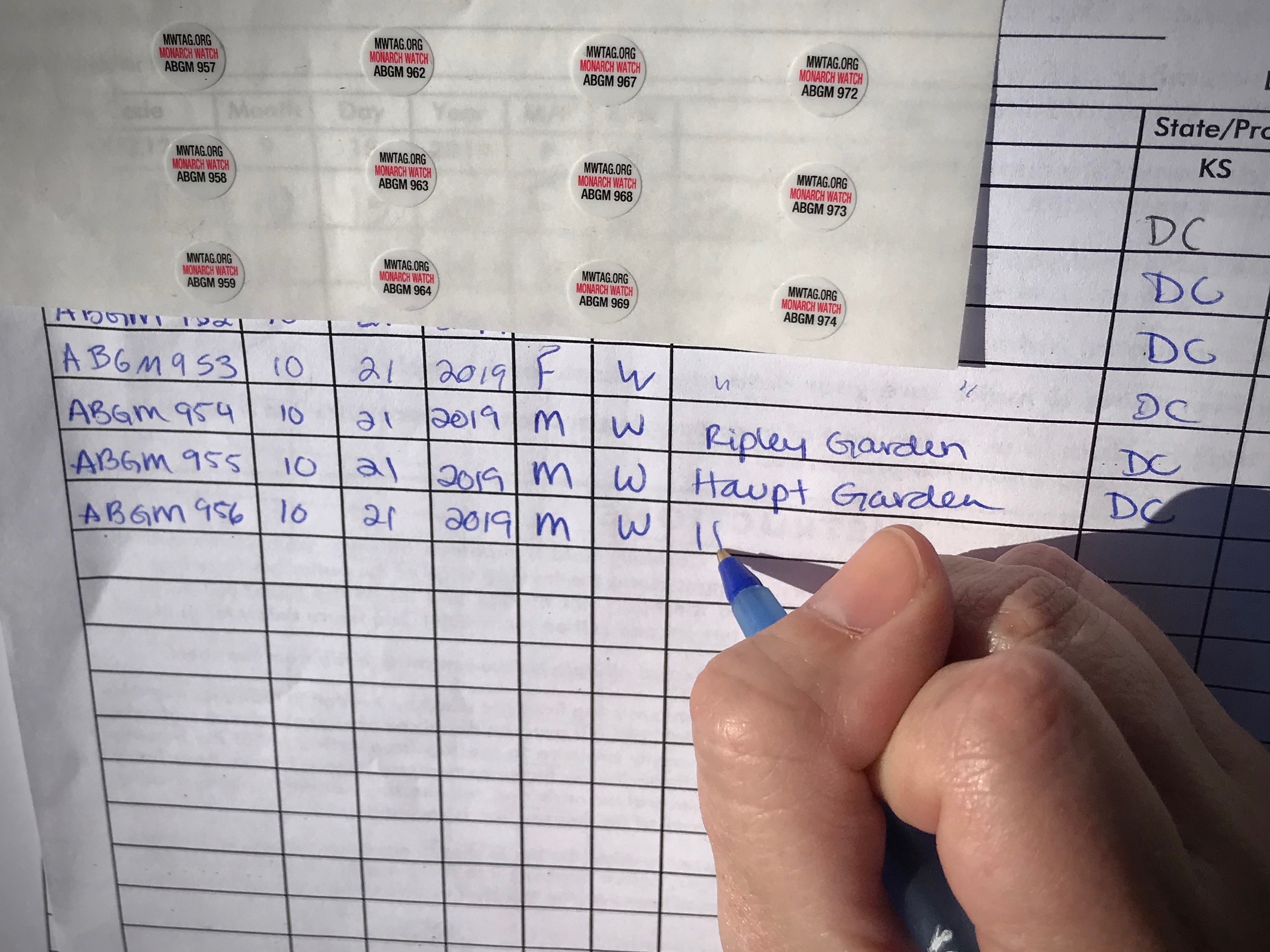

If everything goes right for the recently named butterfly ABGM 9532, he and his new sticker, which won’t affect his ability to fly, will leave Washington soon for Mexico, traveling 25-30 and sometimes hundreds of miles per day. There, using magnetic fields and solar guidance, he’ll try to end up in the very tree his ancestors flew to. And if science is lucky, someone in Mexico will record ABGM 9532’s visit after the monarchs start arriving in November.

Thanks in part to the disappearance of milkweed and other habitat, the Eastern population of monarchs has declined precipitously in recent years. The butterflies arrive in Mexico around the Day of the Dead and stay until March. There’s reason to cautiously celebrate that the population may be rebounding, but it’s all the more reason to track monarchs. Monarch Watch, based in Kansas, will send anyone who wants to help a tagging kit for a nominal sum. This is the third year that Smithsonian Gardens has participated in the count—it tagged about 250 butterflies in the first two years.

After we send ABGM 9532 on his way, Walker produces a female in a terrarium that she brought in case the tagging wasn’t great today. Doesn’t it hurt the butterflies to grasp their wings this way? Walker, an entomologist, assures me it’s fine. They tell me how you know you’ve got a young, strong papillon: They feel like they’re full of “juice,” Schmeichel says, and they don’t shed too much “dust”—a sign they might not be part of the migrating generation. Butterflies can handle a lot of “scale” loss at any rate, Walker says. The sticker is close enough to the monarch’s body that it doesn’t interfere with their balance when flying.

In the DC area, October is often when the monarchs get signals that it’s time to head south. The nights turn cool, and the milkweed starts drying up. Gardens and green patches along their route are like butterfly Wawas, where they can find reliable food, fill up, and get back on the road. Smithsonian Gardens’ current big exhibit is about habitat and includes a number of places where monarchs might make a pit stop, including a monarch waystation” across Jefferson Drive, Southwest, from the Hirshhorn, at the lip of its sculpture garden.

Sarah Dickert, who designed the garden, tells me about the green milkweed she planted this year, most of which didn’t make it, though her nectar plants did fine. Schmeichel bags a buckeye butterfly to show us its beautiful “eyes,” which can help fool predators. But no monarchs, so we move on.

In the Mary Livingston Ripley Garden, we meet another Smithsonian Gardens employee who tells us she’s seen some monarchs over by the verbena. Sure enough, Schmeichel nets another male there; we sticker him before checking out some pipevine swallowtail caterpillars who are hanging out on some Dutchman’s pipe. Schmeichel demonstrates how when they feel threatened, the caterpillars push little orange scent glands out of their heads to deter predators.

The tagging was really good three weeks ago, Schmeichel and Walker tell me. They tag up until about Thanksgiving, depending on the weather. If you see them out with their nets, they’re happy to let you join their party: “Anybody can do this,” Walker says.

The first week of October is showtime for the Smithsonian Gardens monarch-tagging crew. When the nights turn cool and the milkweed starts dying back, that’s the signal for the monarchs that it’s time to go. Neither Schmeichel nor Walker has found a monarch tagged from north of DC, but when supervisory horticulturist James Gagliardi happens by us near the Freer, he says he once found one that had been tagged at Rutgers University before flying to the Smithsonian—a “very educated butterfly,” Gagliardi says. He tells us he’s seen three monarchs on the parterre of the Enid A. Haupt Garden, so we head up there, where another Smithsonian Gardens employee says they may be on the pansies. Indeed, there are two more, both males.

We tag them and take one more lap around the Independence Avenue side of the Castle, where the southern exposure and flowers create favorable conditions for monarchs. But there are none to be found, and we agree that five butterflies is a good day’s work. “We love to have people come out with us,” Walker says.