This has been the summer of Election Day prophecies, none of them good. President Trump has escalated and led an all-out assault on voting-by-mail. His rhetoric has been operationalized by GOP efforts that include lawsuits, prohibition on mail ballots, and efforts to undermine the Postal Service.

What’s going on is clear: Republicans are creating the conditions for an election-night showdown—one in which Trump, pleading fraud and mismanagement, refuses to concede the election if he loses.

Whether he succeeds depends largely on one factor: voter confidence, the measure of voters’ trust in the legitimacy of the election. The erosion of voter confidence isn’t just a Republican problem. On election night, Democrats could be left wondering whether they should trust the results in closely contested Senate races, for example. Putting a constitutional crisis aside, a Biden administration could enter power with a pall of illegitimacy hanging over the federal government.

Can anything avert this nightmare?

Yes, argue some people: turnout. An unprecedented wave of voter turnout—and an overwhelming defeat for Trump—is the simplest way to convince the country (and Trump’s supporters) that he must concede. A public roundtable at the Brookings Institution captured the point, when panelists concluded that “high turnout can also act as a safeguard by increasing public confidence in the election.”

But there’s bad news: Political science has a dimmer forecast for November. A body of research on voter trust and electoral outcomes suggests that Trump’s fear-mongering will likely succeed for a large number of Americans and that there’s little obvious way to counter it.

And massive turnout—while good for democracy—won’t be the panacea that many assume.

The Winner Effect

Trump has several advantages when attacking the legitimacy of the election. The biggest is the changing perception among partisan voters of the election results themselves, a phenomenon known as “the winner effect.”

The winner effect is the resilient tendency of American voters to disbelieve the results when their candidate loses—and to trust the results when their candidate wins. The effect was first described in a 2015 paper by professor Michael Sances and Charles Stewart III, who now leads the MIT Election Lab. Starting with the Florida debacle in 2000, Sances and Stewart showed that the winner effect acts as a polarizing force on voters. Between every presidential election from 2000 to 2016, Democrats and Republicans generally oscillated in their confidence, depending on which candidate won.

Typically, the winner effect is benign. In November 2004, my mother, a hardcore liberal who had voted for John Kerry, began circulating emails from sketchy progressive websites, which claimed that something “fishy” had happened with the vote-tallying in Ohio. Four years later, our hyper-conservative neighbor, who had voted for John McCain, shared her suspicions that voter fraud had something to do with Barack Obama’s overwhelming victory. The seesawing distrust between my mother and her political nemesis, inside the same cul-de-sac, was the winner effect in a nutshell.

When Mitt Romney lost in 2012, nearly half of Republicans did not trust the results. “There’s already fertile ground in the Republican Party to doubt the legitimacy of the election,” says MIT’s Charles Stewart.

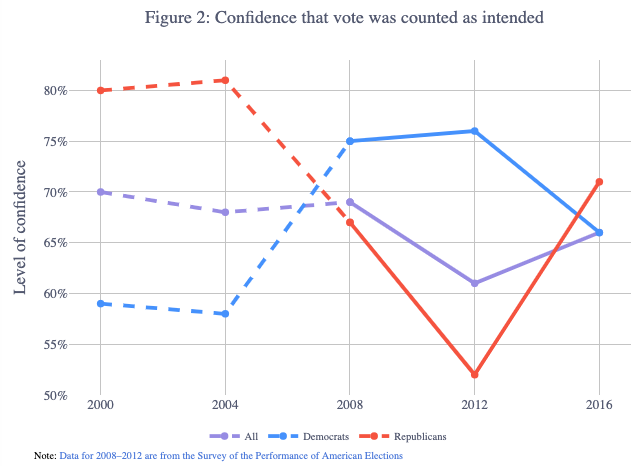

A chart from the MIT Elections Lab illustrates how the two parties have perceived the election results since 2000. It also shows something else about the winner effect: It’s not static, but rather has evolved over time, allowing for changes in partisan pressure and political context:

As the regression above illustrates, Democrats and Republicans have not experienced the winner effect equally over time. Even though Democrats have lost three of the last five presidential elections, the party’s confidence in the electoral outcome has ticked slightly up. And while Republicans have won three presidential elections, their trust has subtly trended downward.

These trends are captured in two different presidential elections: 2016 and 2012.

The 2016 election was a Black Swan event. Donald Trump won hair’s-breadth victories in typically blue states like Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin. It was a razor-thin outcome, awash in allegations of Russian meddling and social-media influence. And yet, polled afterward, Democrats were about average in their willingness to believe that the election outcome was legitimate. They also showed higher levels of trust than after their losses in 2000 and 2004. Even when Donald Trump achieved an upset odds makers had pegged at merely 15 percent, a robust majority of Democrats—66 percent—believed the outcome was fair, just five points shy of Republicans.

Compare that to 2012, in which Mitt Romney lost to Barack Obama. That year saw a flatly boring election night: The projections were spot-on, the result was called shortly after 11 PM, and the losing candidate graciously conceded defeat. Yet polled afterward, a record number of Republicans said they did not trust the veracity of Romney’s loss—with only 52 percent saying they had confidence in the results.

In other words, the last time a Republican nominee lost a presidential election, 48 percent of his supporters—effectively half the Republican Party—did not trust the legitimacy of the election.

After 2012, Stewart conducted his own poll and found evidence of even darker beliefs. “I found that about a third of Republicans thought that Mitt Romney was robbed,” he says.

If one of the core messages of Republican rhetoric is to doubt expertise, it could be that this rhetoric is sliding over into elections.

One explanation is that Trump’s rhetoric as a candidate in 2016—casting doubt as to whether he would accept the result and pushing false allegations of voter fraud—polarized both parties’ responses to the electoral outcome, priming Democrats to trust the outcome more and Republicans to trust it less.

But Stewart also thinks it’s possible that, over time, divergence in Democratic and Republican confidence has something to do with the ideologies of the two parties: one channeling the competence of government administration, the other channeling a grievance agenda of government malfeasance and deep-state conspiracy. “If we think that one of the core messages of Republican rhetoric these days is to doubt expertise, it could be that this rhetoric is sliding over into the administration of elections,” suggests Stewart.

In addition to this long-term evolution, there’s another big factor at work: Party rhetoric. Trump’s daily assault on the election process—along with the acquiescence of Republican leadership in going along with it—is almost certain to enlarge the winner effect. “The public takes their cues from political leaders,” says Stewart. And unlike Romney, Trump has never accepted the “gracious loser” norm that guides tradition in American politics—a norm that Stewart thinks “has probably buffered the public from becoming totally cynical when their candidate loses” in past years.

All this suggests that Republican partisans are primed to disbelieve the election results by historic proportions in 2020. “There’s already fertile ground in the Republican Party to doubt the legitimacy of the election, should [Trump] lose,” Stewart says. “The difference here is active hostility toward election administration on the part of one of the candidates. And it seems to be integrated into party rhetoric in general.”

“If he loses,” Stewart later added, “I suspect that Republican trust in the electoral outcome will hit new lows.”

High Turnout Doesn’t Mean High Confidence

Could unusually high voter turnout reverse the impact of presidential rhetoric and the winner effect? No, says Stewart. Conducting a thorough review of the literature in political science, Stewart finds “only a weak causal connection between voter confidence and voter turnout.” In other words, a big boost in voter turnout does not affect voters’ perception of whether the result was legitimate. That perception is far more influenced by other factors, Stewart finds, such as partisan identity and racial affinity.

Although turnout itself does not impact the confidence of voters, turnout can shift confidence in a secondary way: the margin of victory.

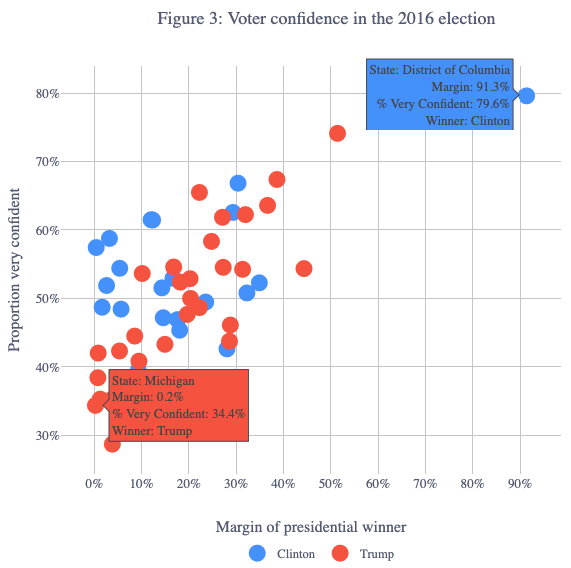

At MIT, researchers have shown a correlation between tighter statewide margins of victory and lower confidence in the statewide outcome. Take 2016. In Michigan, one of the slimmest-margin states that year, trust in the outcome was one of the lowest in the country. By contrast, Washington, DC, the jurisdiction with the widest margin of victory, had the greatest voter confidence in the United States.

But the psychological effect of margins is one reason that big turnout may hurt—as much as help—voter confidence in November. At the moment, Joe Biden is leading Trump nationally by a margin just shy of 8 percent—well above the 4 percent a Democrat generally needs to win the Electoral College. Even if turnout surges for Biden on Election Day, a minority of highly educated voters will interpret this as a national landslide. But in individual states—during the drama-filled days and weeks after Election Day—voters will experience Biden’s national victory as a series of much slimmer state contests. This will especially be true if Biden manages to eke out narrow victories in battleground states that Democratic strategists have been salivating over: states such as North Carolina, Georgia, Arizona, and even Texas.

On paper, the national map may look overwhelmingly blue. But the research on voter confidence suggests that by winning these slim victories, Biden will be creating new constituencies of voters who exhibit very low trust in the results of the election, especially in states with a long history of voting Republican. And their Republican governors, legislatures, or secretaries of state may be more poised to respond to Trump’s provocations—whether it’s refusing to concede or continuing to sow doubt—while the ballots are being counted throughout November.

“Voters pay attention to what’s happening locally,” says Stewart.

“One outcome of this election may be to expand the “battleground” waterfront. . . . That could very well reduce the degree to which people are confident in their own state.” Stewart emphasizes that state margins of victory don’t correlate as well to confidence in the national result. But the MIT Lab has shown that confidence in national outcomes is generally lower than confidence in state and local outcomes.

By themselves, these two ingredients have the potential to create a volatile recipe: a political party that’s historically poised to distrust the election’s outcome and a Biden victory poised to create new constituencies of these Republicans to vociferously and angrily dispute the election.

The Wild-Card Factor: Election Administration

Is there any good news? Yes—kind of. There is a well-known bulwark for voter confidence: competent election administration. Studies have found again and again—in 2003, in 2008, in 2009, and twice in 2015—that a voter’s experience on Election Day impacts how much he or she trusts the result. As one study by Lonna Rae Atkeson and Kyle Saunders summed it up: “The more enjoyable and positive their vote experience, the more likely they will feel that their vote will be counted.”

Researchers have known that people who vote by mail show lower confidence in the election’s legitimacy.

What’s the downside? The downside is that it’s unlikely voters will perceive the election as a paragon of competence in November. They’re more likely this year to encounter the factors that negatively impact voter trust. One factor is long lines and wait times. A second is how well trained poll workers are to program machines and run the precinct smoothly. And a third factor is how long it takes to report the election results: The longer that voters are kept waiting to hear the winner, the more their trust in the outcome diminishes over time. Thanks to work by Stewart and Sances, as well as Atkeson and Saunders, we know that delays in tallying the result is correlated with diminished voter confidence in the election’s legitimacy, particularly in close races.

Already this year, these negative factors are on full display. In Georgia last June, voters waited in lines until 1 AM to vote. The reason? Administrators were struggling to program a new set of machines that had been purchased by Georgia—one of 14 states to upgrade their voting technology in recent years. That’s put pressure on local officials to conduct the election on novel and unfamiliar systems, often for the first time in 2020. And when it comes to election-night results, abacus-counters have begun to warn that we may not know the presidential results for days or even weeks. As Politico Magazine reported, a massive surge in mail-in ballots will probably lead to a slowdown in the vote count, with clerks overwhelmed, the Postal Service overrun, and thousands of ballots left in the trash.

This leads to the final factor that negatively impacts voter trust: vote by mail.

Researchers have long known that people who vote early, vote absentee, or vote by mail show lower confidence in the legitimacy of the result. “Paper absentee ballots . . . appear to have the largest negative effect on confidence,” concludes one 2008 study from the Journal of Politics, ranking it alongside digital-only voting machines (most of which have since been phased out). Atkeson and Saunders have found that “voting absentee or early . . . results in less voter confidence.” They add, “Voters engaging in absentee voting, for, example, may feel that their ballot is less likely to be counted.”

“Yes, putting your ballot in the mail lowers your confidence,” says Stewart.

Stewart raises a few caveats, however: Voters who deliver their ballot at a vote center, or “drop box,” don’t show a disparity in confidence, as opposed to those who use the Postal Service. (This is possibly because states that use a vote-center system, like Colorado, are often case studies of administrative excellence.)

And Stewart suggests that, in 2020, election officials may be a bulwark for voter confidence overall. For most voters, he writes, “bad experiences are rare.” Stewart describes data from this year’s Pennsylvania primary, showing that voters had a good experience despite long lines and delays in tallying. And voters’ experiences are not the same thing as fire-and-brimstone media coverage. “News accounts of on-the-ground election administration are orders of magnitude less positive than what voters experience themselves,” writes Stewart.

That could mean that a big chunk of voters’ confidence in the legitimacy of the 2020 election comes down to one thing: how well local and state election officials hold up under the pandemic.

Bottom Line: Trump Has the Advantage

But the importance of how voters perceive election officials is just a reminder of why Trump has spent so much effort undermining them.

The winner effect “depends on elite behavior to reinforce it,” says Stewart—and party loyalists take their behavioral cues from elites. So “if one party seems at odds with election administration, in general, it’s going to affect what, up until now, has been a balanced response by partisans to election outcomes,” he says.

If Trump can polarize the administration of the election, it may serve to neutralize the one factor that would otherwise boost confidence in the outcome’s legitimacy. Whether he knows it or not, Trump’s rhetoric is an attempt to leverage the winner effect so dramatically that it overwhelms Republicans’ experience with the election: dampening their enthusiasm for competent election officials and enhancing their paranoia and suspicion if the election becomes tangled in long lines, lawsuits, and delays.

In either case, it all comes down to Donald Trump and a President willing to shrug off critical norms on election night. If the occasion finds him spewing half-baked fantasies about fraudulent mail voting or corrupt ballot counters, the research suggests that Trump will have a built-in constituency of Americans ready to believe him.

“If the guy you voted for loses and he says publicly, ‘The people have spoken,’ his supporters will respond one way,” Stewart sums up.

“If he says, ‘I wuz robbed,’ they will respond another.”