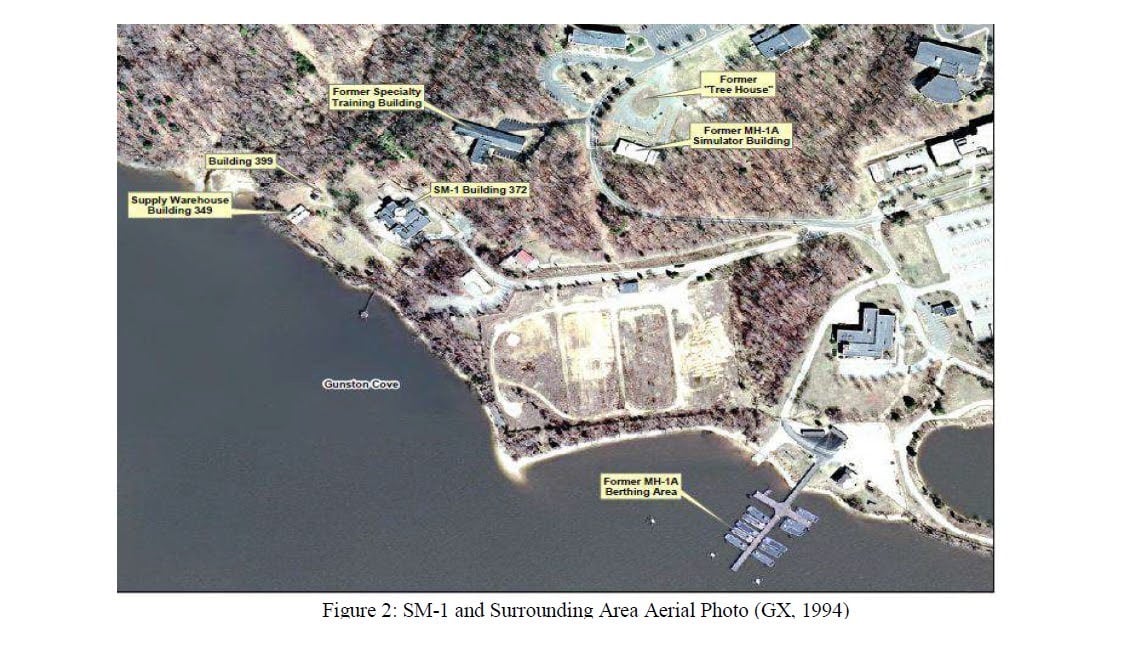

Potomac boaters have seen, at least part of it, for decades as they fished or played on the river near Fort Belvoir: An approximately eight-story-high white smokestack that’s currently home to an osprey. There’s a duck blind nearby for on-base hunting, near a large outfall pipe you can see at low tide and an old pier that conceals an intake pipe.

These images are all that most people will ever see of the SM-1 nuclear reactor that’s sat on Fort Belvoir, unused since 1973, when the Army shut it down and removed its fuel rods and waste. It turned the former “Atoms for Peace” training reactor into a museum a few years later. But the only people who could visit were others in the military or those who could get on base to the highly restricted “300 Area.” The museum closed a decade or so later.

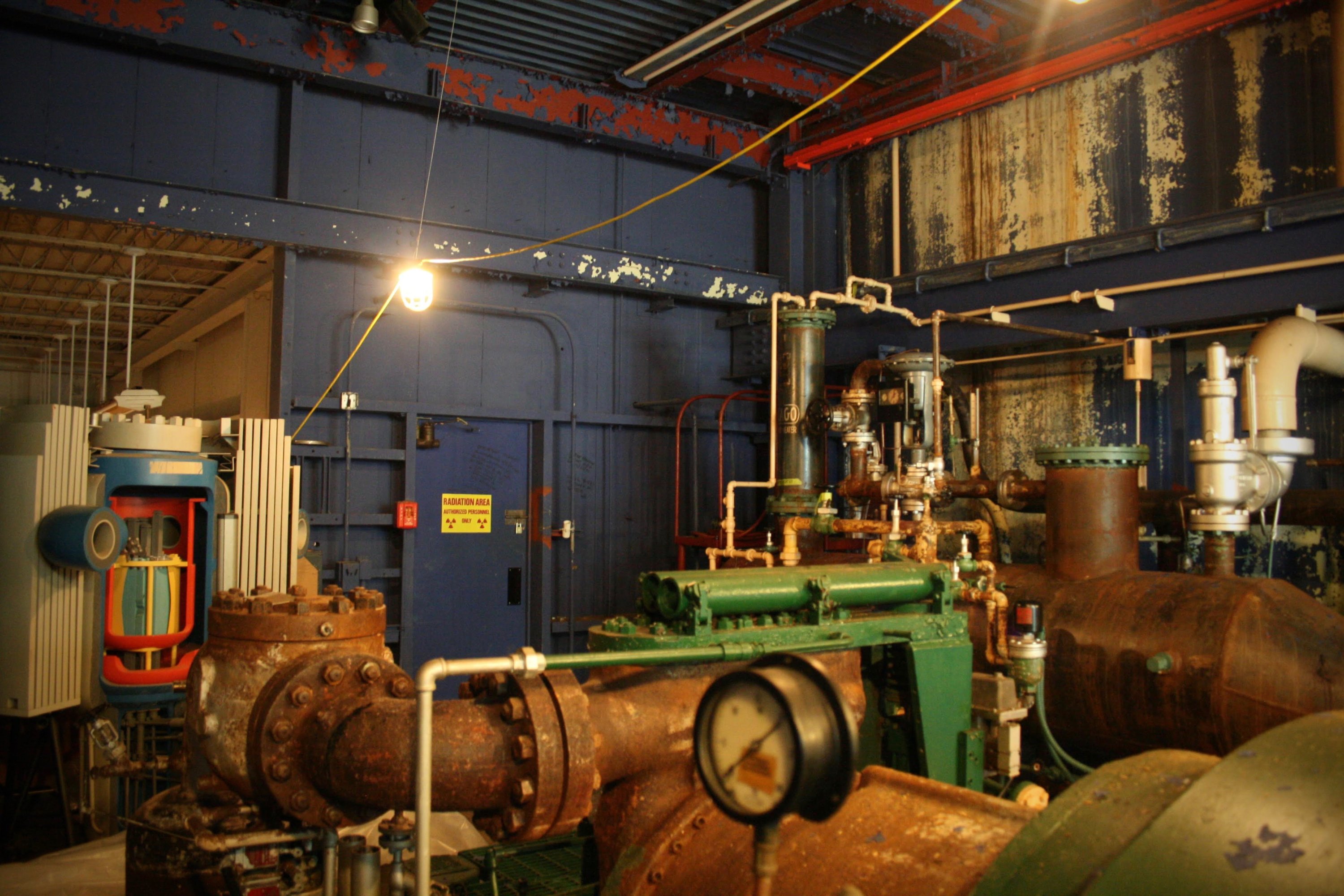

Now, in a wooded corner of Fort Belvoir, all that remains of an ambitious program to allow the military to generate power wherever it went is a decaying building filled with, well, decaying radiation.

The plant was called SM-1. That was short for Stationary, Medium-size reactor, the first of its kind, built in 1957. (The Army later built a stationary reactor in Fort Greeley, Alaska, and a portable one, PM-2A, to Greenland. Other reactors part of the Army Nuclear Reactor Program were stationed across the world either through the Army or other military branches. ) While the 2 megawatts of power it generated aren’t much by the standards of today—Dominion’s Possum Point power plant 12 miles down the Potomac generates more than 800 times as much electricity from gas and oil—it was the first nuclear reactor in the United States ever connected to the commercial power grid.

SM-1 represented the military’s hope that nuclear power wouldn’t just be used on ships and submarines but could harness the power of the atom to power American military facilities throughout the world where resupplying would be difficult. It was also where the Army trained nuclear operators from across all the armed forces.

Around the same time, the Army also developed mobile reactors, some that could be put on a flatbed and put on a standard Air Force cargo plane, and a ship, the Sturgis (MH-1A), a former Liberty Ship that was stripped of its propellers and turned into a towable nuclear power plant. It was docked right by SM-1 when it first achieved criticality in 1967. Sturgis was later sent to help power Panama Canal operations until 1977.

Still, some harbored understandable concern about bringing a mobile or temporarily stationary nuclear reactor into a combat zone. Studies from the Army and the GAO eventually determined the reactors were too costly to continue operation, so one by one, they were shut down. Belvoir’s SM-1 ran the longest, and Sturgis was the last operating project. It was decommissioned and finally dismantled and scrapped last year.

It’s rare for nuclear facilities to be wiped off the face of the earth, especially in America. That’s in part because the US is well behind the times in managing nuclear waste, compared to countries like France that have mastered not only the disposal of such waste but also how to recycle fissile material. Fortunately, because of their small output and footprint, facilities like SM-1 are able to be remediated more easily than the bigger commercial facilities that followed.

The Army Corps of Engineers, which is overseeing the remediation project, hopes to return the ground under SM-1 to usable land within the next few years, perhaps by 2025. But first, it has to remove the most radioactive material, which remains in a sealed containment vessel that was briefly (and in unauthorized fashion) painted to resemble an 8-ball. The Army Corps of Engineers will work with an Alexandria-based contractor to dismantle and dispose of what’s left.

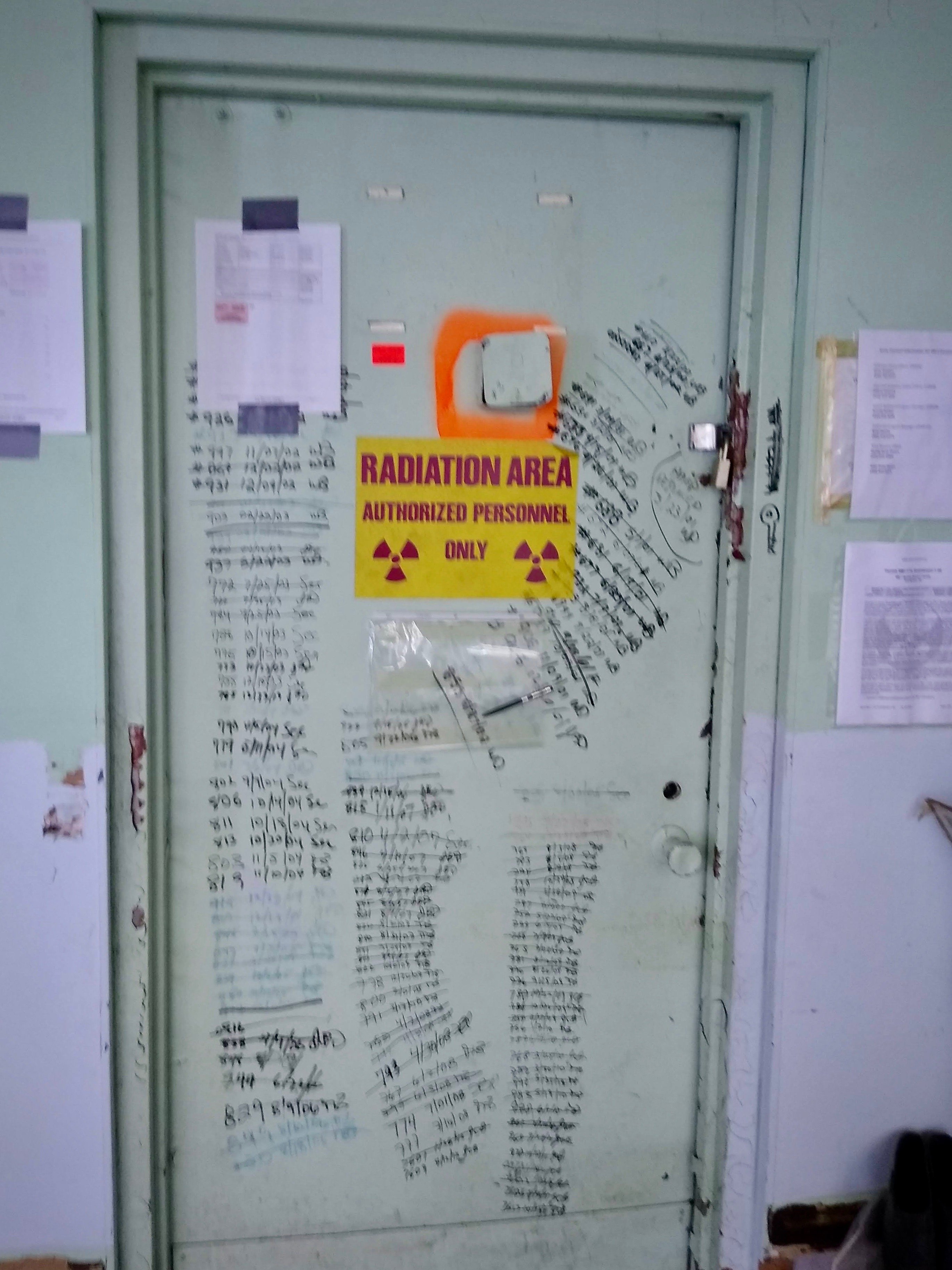

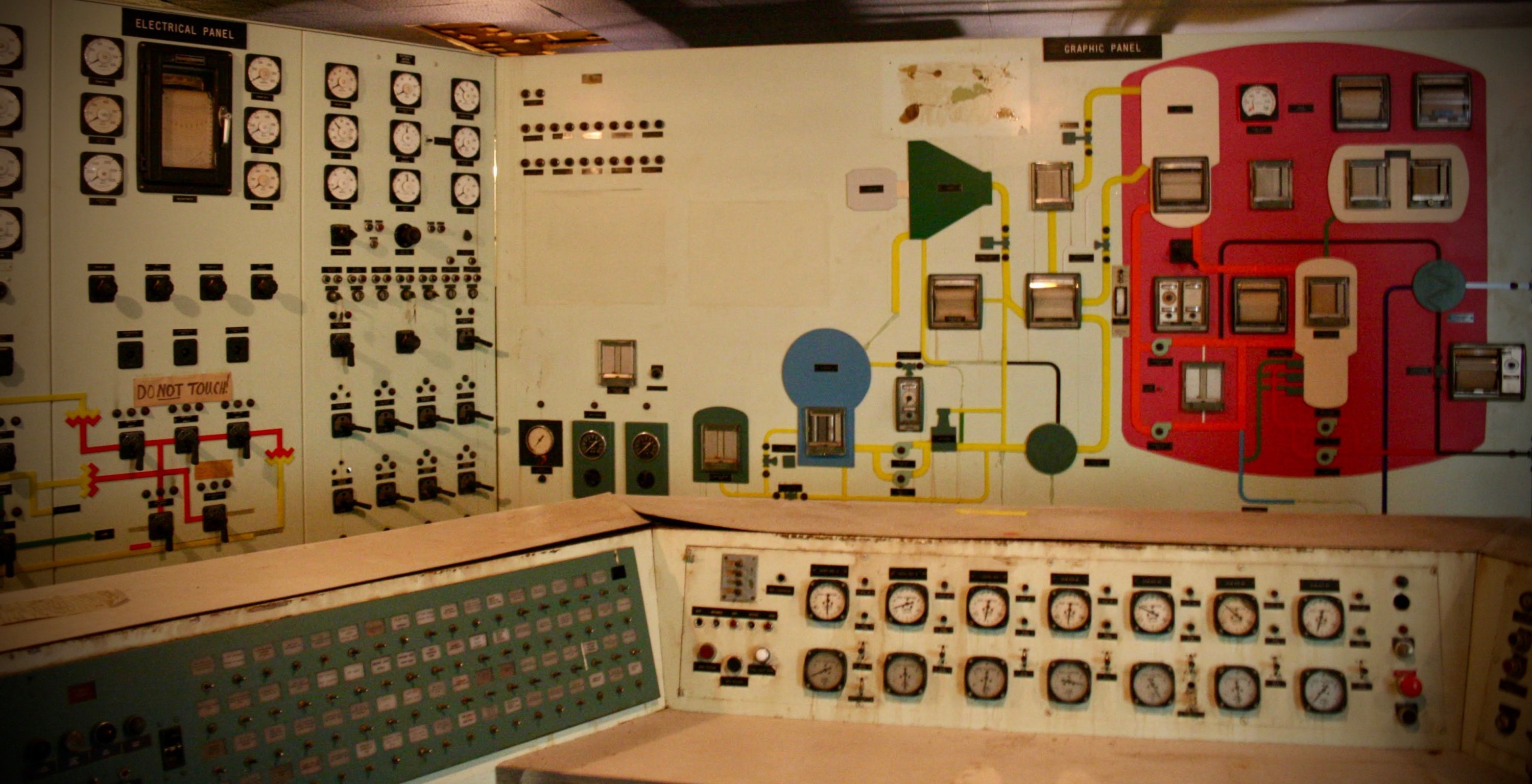

That’s a complicated task: When SM-1 closed in 1973, all spent fuel and critically radioactive parts were removed, but the business side of the building where power was generated still has latent, low-level radioactivity.

The Army Corps of Engineers has monitored SM-1 for decades, installing dosimeters, which measure external radiation, within the complex and outside its walls. The Army is not going to come in with a wrecking ball, says Brenda Barber, who’s the Army Corps’ project manager; rather, it will carefully deconstruct the parts that remain radioactive and will send those parts to federally approved sites before the rest of the SM-1 complex comes down.

Then, the Army Corps of Engineers will remove and replace the soil on the site, and the intake and outfall pipes you can see from the Potomac River, in Gunston Cove.

If all goes to plan, Fort Belvoir’s 300 Area, which is home to several Department of Defense agencies whose bland names suggest much more interesting work is going on inside, will have a few acres more space to do whatever it is they do there. But, before then, a bit of nuclear history needs to be erased.