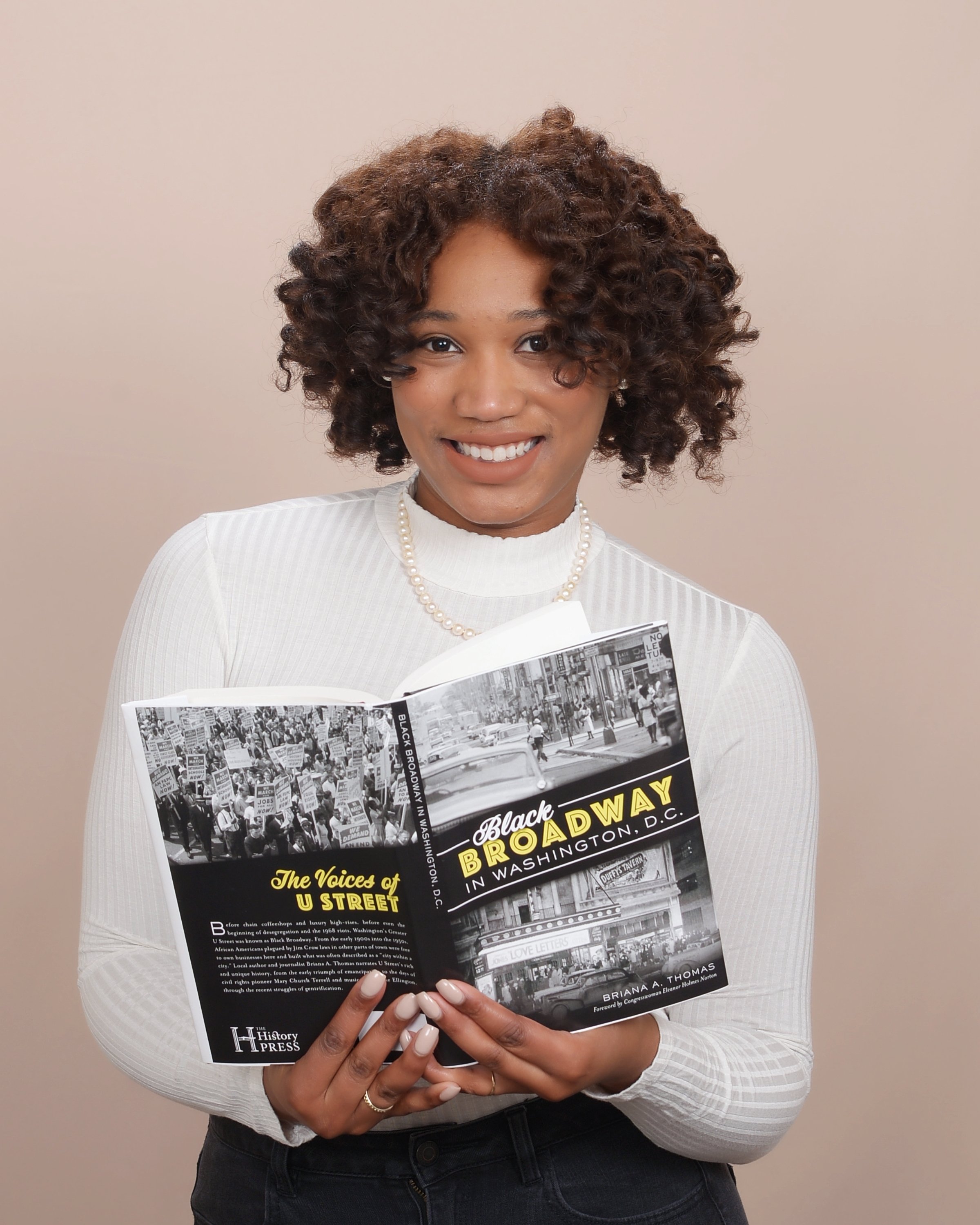

Briana Thomas was thinking about the legacy of U Street when she watched Kamala Harris get sworn in as vice president on January 20. The local author, who released Black Broadway in Washington, DC that same month, saw the connection: “We had our Vice President Harris become the first Black woman vice president and she’s a Howard University graduate—another first that’s connected to U Street,” says Thomas. “It’s just never-ending.”

Other historic milestones from the corridor: The first Black public high school in the country (Paul Laurence Dunbar High); the nation’s first Black Y (Twelfth Street YMCA); and the first Black-owned bank in DC (Industrial). Those who were born and raised on U Street went on to create major inventions, such as Dr. Charles Drew, who created the first blood bank. Some of this powerful history crossed Thomas’s desk when she was an editorial fellow at Washingtonian magazine in 2016. She wrote “The Forgotten History of U Street,” a photo essay that explored the rich Black Broadway era between the 1920s and 1950s, and from that assignment grew her book. We talked to Thomas about the influence of U Street, her memories and inspiration for the book, and the stories that stuck with her.

How did you get involved in doing this research?

Even before [the photo essay], I was already familiar with the history of U Street because of my grandmother, Evelyn Thomas, who moved from Suffolk, Virginia, when she was in her early 20s, which was pretty typical around the ‘50s. Women and live-in servants would migrate from the south to get better jobs in DC because there were more opportunities for Black people on U Street during that time. My grandmother used to work for the federal government.

I can remember her taking me to different places when I was younger. She took me to shows at Howard Theatre, the Lincoln Theatre, Bohemian Caverns—that’s maybe one of her favorite spots and if she reads this later she might get me for this! [Laughs.] She would tell me about the jazz scene on U Street, how she would go see different shows and the dancers, and [Caverns] was a hot spot. I mean, every time she talks about U Street her face literally lights up. It’s like there’s no bad memory of U Street, at least for her during that time.

What pushed you to continue working on the project and start writing a book?

When I started doing the photo essay, I really fell in love with the project itself—meeting the people, like the Ali family at Ben’s, and Lee’s family, who are all such sweet people but they also have so many great stories. A lot of people ask: “Is the history on U Street lost?” When I was interviewing, I would ask, “Do you think that the Black Broadway era could ever be repeated or redone?” Of course, everyone’s answer is like no. We can’t go back in time and do this again, U Street is totally different, property taxes are so high that businesses are shutting down left and right, the residents that built this community can no longer afford to live here and enjoy what they built. I think that was my push to write this book because I don’t think the history–maybe no, it can’t be repeated—but I don’t think the history is lost. But I do think that there’s more we can do to make sure it’s not overlooked.

Do you have a favorite detail from your research?

Duke Ellington, who grew up on T Street within the U Street corridor—I don’t know why this is such a fun fact to me, maybe no one cares [laughs]—but when he was growing up, over the summer he actually sold ice cream at Griffith Stadium. To me, it just continues to show the people that we see as celebrities and notables and history-makers still had a normal life outside of making history. Like, he’s just a normal kid selling ice cream down the street and then we’re still talking about his music in 2021.

What do you think of the resurging popularity of efforts to support Black-owned businesses as part of a greater Buy Black movement? It’s kind of recreating what was ingrained on U Street decades ago.

It’s a good thing that people are being woke, if you will. “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” was something that the New Negro Alliance started on U Street in the 1930s because they got fed up with patronizing different stores, markets, clothing stores that wouldn’t hire people of color. They started this movement, literally—now we see fast forward in 2020, 2021 where we now have places like Facebook telling us where Black businesses are. I think it’s really full circle. That’s something that Alliance did: They printed out a pamphlet of all the Black businesses in the area so that people could go and literally buy Black. Now, decades later, you see this happening again; it shows that the history is not lost, we can save it, and there’s still hope for revival. We did this before and it was successful, let’s try this again.

It was a thriving time—there are so many photographs of joy in spite of the segregation beyond those blocks.

I think that’s what makes it special. In the middle of something negative, there were groups of people that decided to come together and make something positive. In the photo essay, B. Doyle Mitchell, the owner of Industrial Bank, he talks about his grandfather.

“[[Segregation] kept us all in the same community and patronizing our own businesses. We learned to produce and provide everything we needed, and because of that the community flourished.”]

He was saying that, for them, segregation was a good thing. Of course, saying that sounds crazy—but then segregation, something so negative, ended up being a positive. They were able to build their own, without the restrictions of you can’t shop here, you can’t buy a house here, you can’t even walk near a person that doesn’t look like you. Without that trauma, there would not have been these inventions and innovations.

Is there one person whose narrative really inspired you?

Eddie Lofton, the owner of JC Lofton’s Tailors. It’s been passed down for generations. He is DC proud, a born and raised Washingtonian and he knows the history. He has a very colorful personality. He was really able to walk me through his grandfather’s [story] of working in upholstery. There are a lot of big name voices in my book, but it’s the unnoticed voices that stick out to me. They’re talking to me like we’ve known each other our entire lives, and that’s the spirit of U Street. He talks about gentrification and how now he has to use Yelp to get business in his store, but it’s about growing with the times and not being afraid to open your doors to all people. His stories really stuck with me. It’s the tailor on the corner who’s willing to help his fellow brother and sister. He sees a single mom who can’t afford to get school clothes the right size, but he wants to help out. That’s the real heart of the area.

U Street still has so much influence as a meeting place and a site of activism, like Moechella. What does it mean to Washingtonians now?

Gentrification is nothing new, we see it happening everywhere. DC isn’t unique in that. But I do think it’s unique in that we’re going to keep this voice—I actually call it this rhythm—alive. #DontMuteDC was like no, this is our homegrown go-go music. This is how we grew up, this is what makes us happy—we dance whether it was something terrible that happened, whether it’s something good that happened. We had go-gos when President Barack Obama was inaugurated. This belongs to us. And I think it’s that spirit and that rhythm that’s still on U Street to this day, which is why you can have Moechella and the #DontMuteDC movement that becomes nationally recognized. Although the corridor is only so many streets, the spirit of the community is still much larger than that.

There’s still places and things that we can see and point back to say, “Oh yeah, that’s my history.” So I think that’s why it happened on 14th and U. It was just like, “Let’s keep this going, no this isn’t over, this train is still going.” There’s still things to be accomplished and we’re not gonna quit just yet.

Before the pandemic, U Street was still a super popular nightlife hangout. You’ve had late nights there. After exploring the buzzing dance and music scene on the historic Black Broadway, what’s the comparison?

I can remember my times on U Street, of course not anytime recently, for multiple reasons. I can think of a specific instance when I was leaving Marvins and in the middle of the street—I’m not lying to you—there was a flash mob. People are breaking out dancing, having a good time, there’s somebody playing drums on the sidewalk and it was just like oh my goodness, is this actually happening? It wasn’t choreographed or anything, it was just like one big party broke out out of nowhere. When I’m thumbing through and researching when people tell me how big of a nighttime scene Black Broadway was—when I think back to those memories and my memories, I’m like yeah the rhythm is still definitely there. Everybody has at least one moment on U Street where you felt happy, where you felt joyful, where you felt free. Everybody just wants to have a good time, we want to have fun, we want to dance the night away—it’s just freedom, free to be whoever you want to be.

See Thomas speak about Black Broadway in Washington, DC at a virtual book talk hosted by Politics and Prose on March 1 at 6 PM. Register here.

This interview was edited and condensed for clarity.