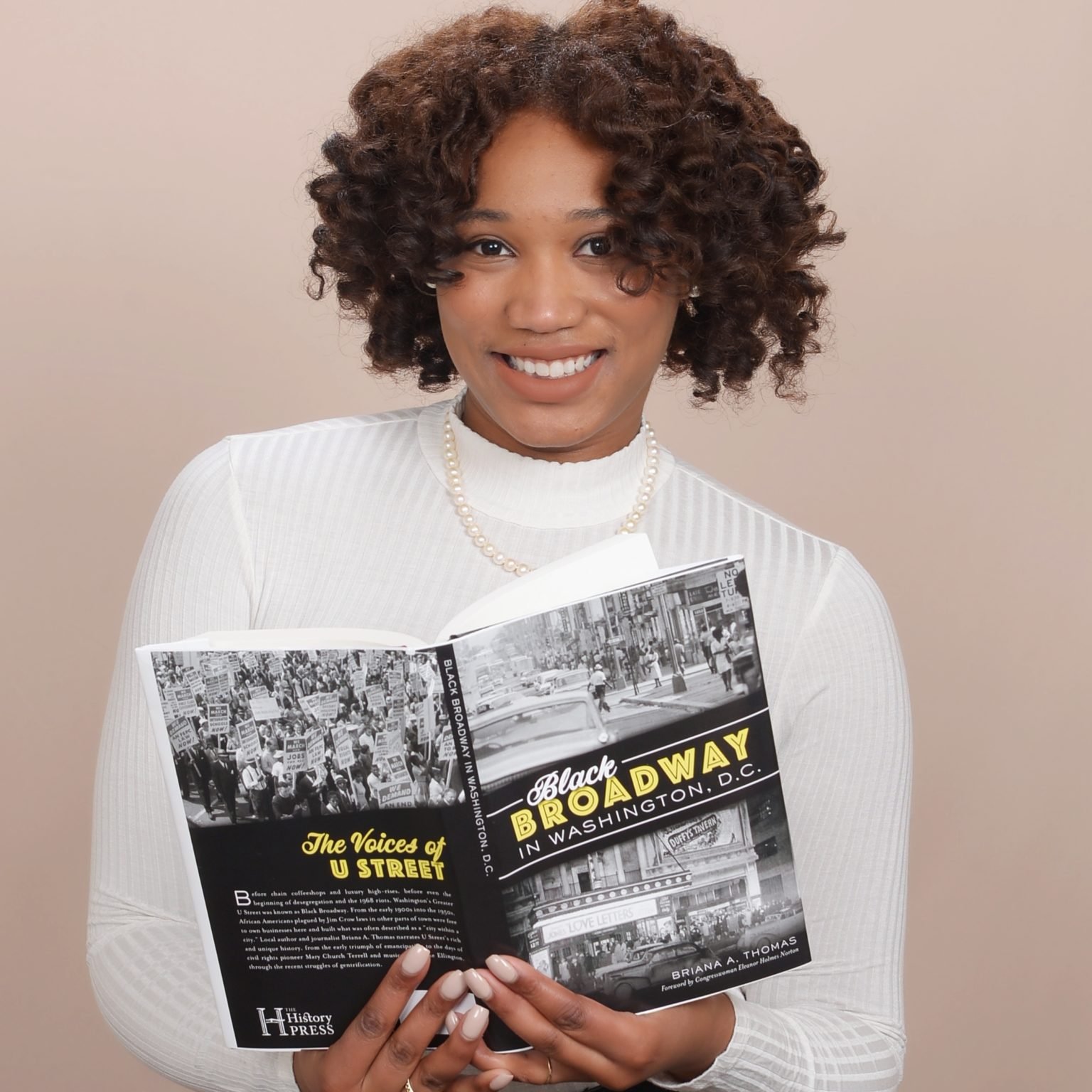

Before Shinola and luxury high-rises, before even the beginning of desegregation and the 1968 riots, the U Street corridor was known as Black Broadway. From the early 1900s into the 1950s, African-Americans—subject to Jim Crow laws in other parts of town—were free to own businesses here and built what was often described as a “city within a city.”

Unsegregated concert halls and nightclubs hosted round-the-clock performances by the likes of Pearl Bailey, Cab Calloway, and Sarah Vaughan. Hundreds of black-owned businesses patronized solely by African-Americans—and funded with loans from the city’s oldest black-owned bank—flourished. Black Washingtonians sent their kids to day camp at the country’s first African-American YMCA, worshipped together in scores of neighborhood churches, and launched a movement against segregation from Black Broadway’s many gathering places.

By the 1960s, the area had birthed some of America’s most influential black leaders and intellectuals—the great jazz-band leader and pianist Duke Ellington and the world’s first renowned black opera signer, Madame Lillian Evanti; the pioneering Dr. Charles Drew, who created the country’s first blood bank; lawyer and Howard University professor Charles Hamilton Houston, whose famed student Thurgood Marshall prevailed in Brown v. Board of Education.

“Everybody knew everybody,” says Richard Lee, whose parents started Lee’s Flower Shop at 928 U Street in 1945. “We didn’t miss going downtown. We didn’t give a shit. I mean, excuse my language, but they wanted to have all that stuff to themselves, fine—we had all this stuff to ourselves.”

Here’s a look at the booming U Street Corridor in those heady days before desegregation and, more recently, gentrification changed everything.

***

Business was kept within the community.

“We had bigtime architects in the community, and I remember a deposit from one of them—I don’t know who paid him this kind of cash money, but his secretary came in with $20,000. That’s like $115,000 today! She had a bag from the Safeway like she’s got groceries, and she reaches down in there and pulls out all that money.” —Virginia Ali, who worked at Industrial bank before starting Ben’s Chili Bowl in 1958 with her husband, Ben.

***

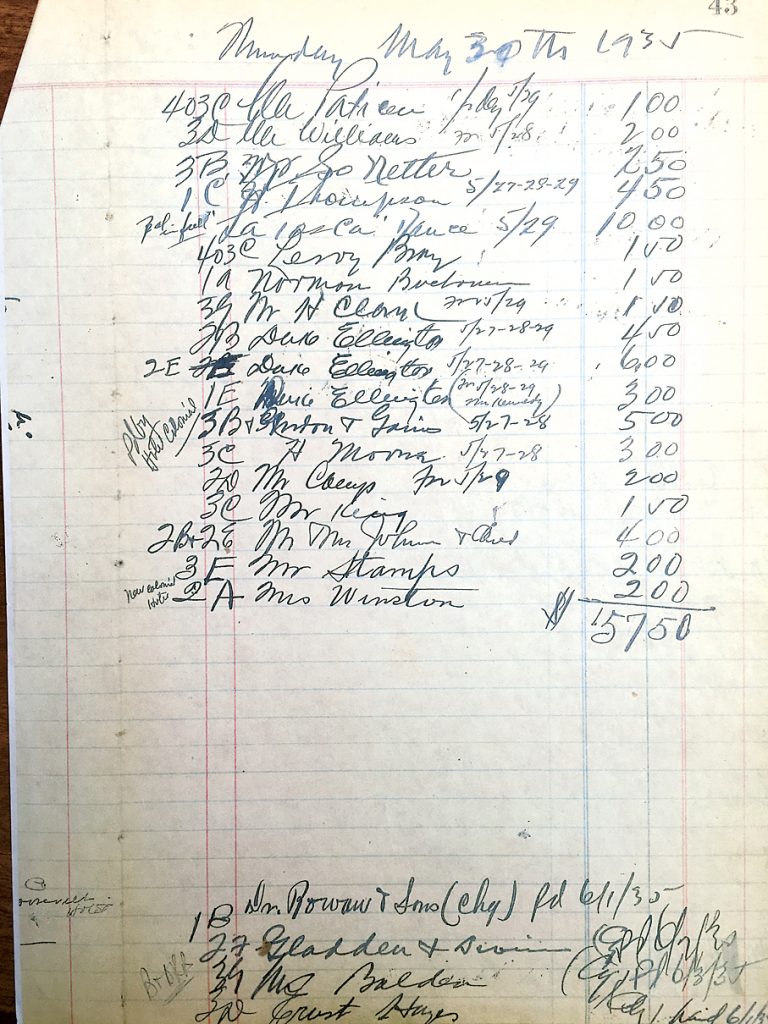

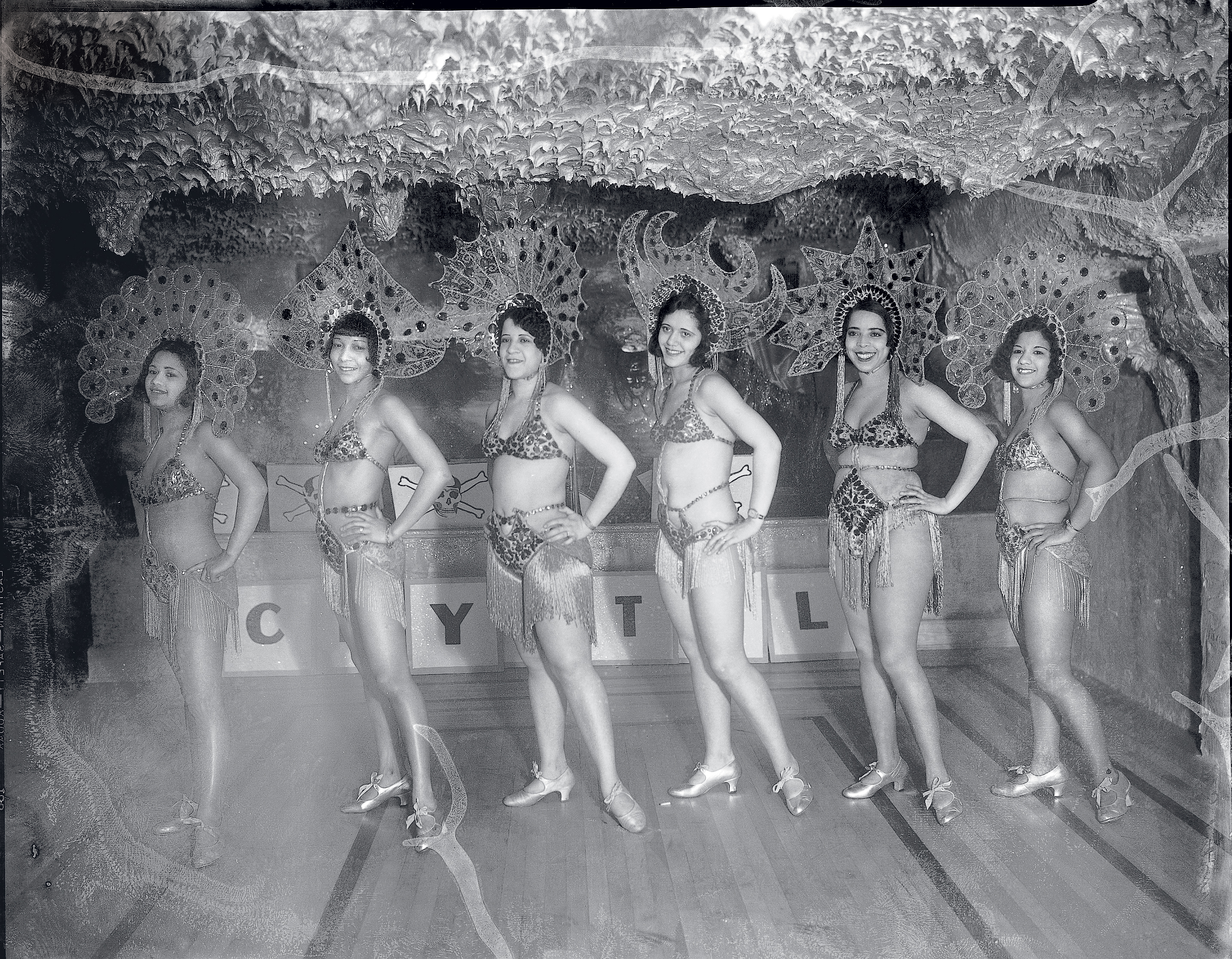

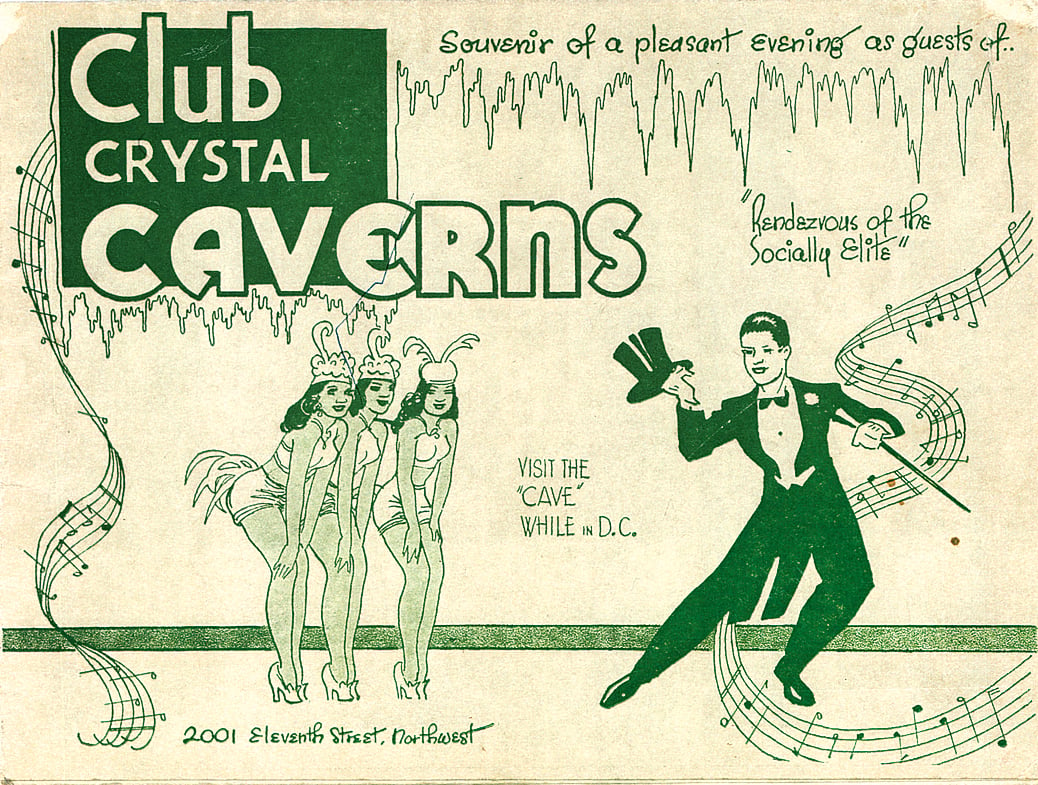

It was the height of jazz.

“The jazz scene was fantastic. We had the Hollywood at Ninth and U, Crystal Caverns across the street, Club Bali at 14th Street. There must have been 15, 20 clubs. There were a lot of cats—and here is the thing about Black Broadway: You didn’t come down here looking raggedy. You came down here dressed.”—Richard Lee, whose parents, William P. and Winifred Lee, started Lee’s Flower and Card Shop in 1945.

***

The neighborhood hummed day and night.

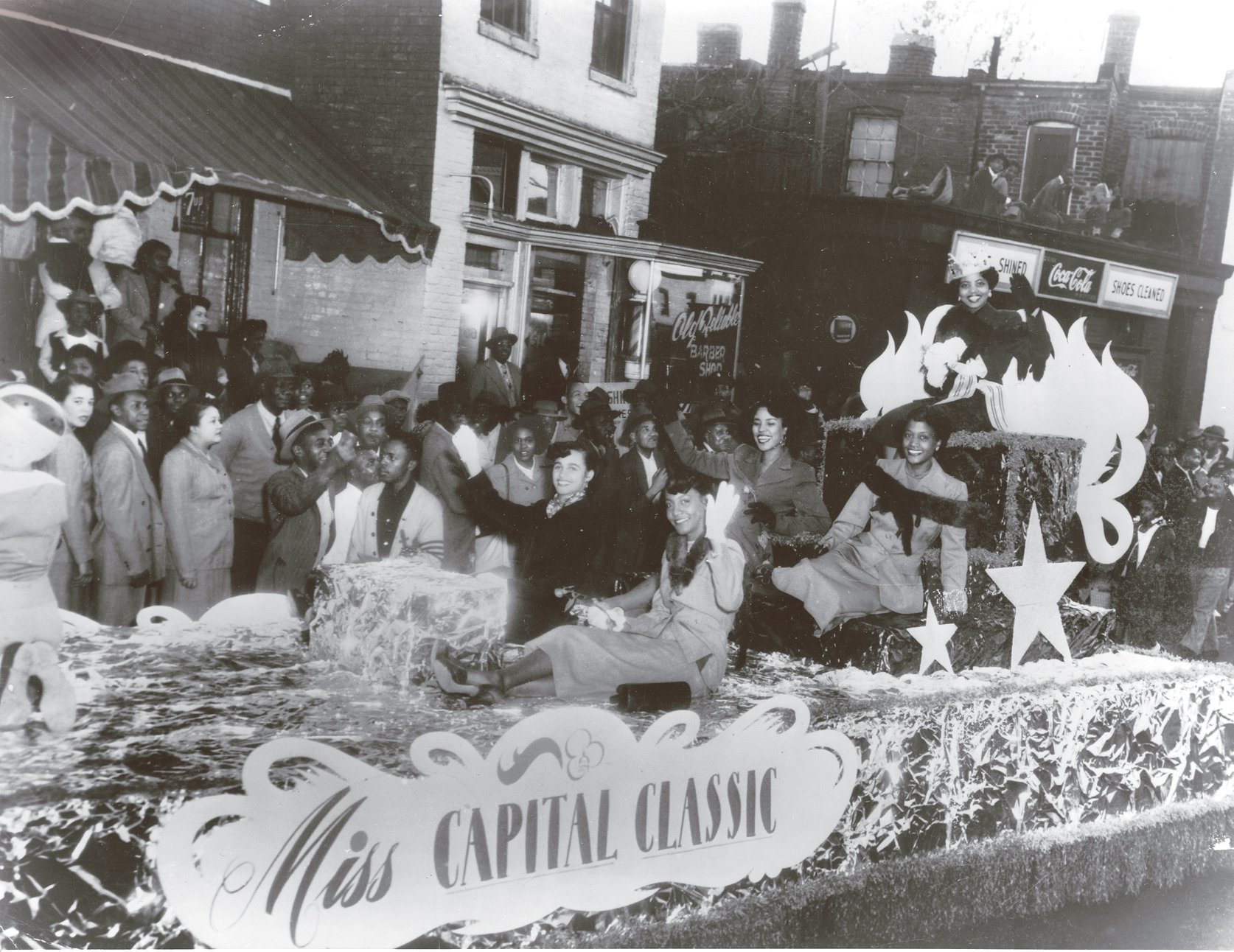

“We used to have parades up and down here almost every Saturday during football season, and they all had queens and floats and bands. Every queen had to have a big bouquet. They would stay up all night sometimes, my mother and father, putting the bouquets together.”—Richard Lee

***

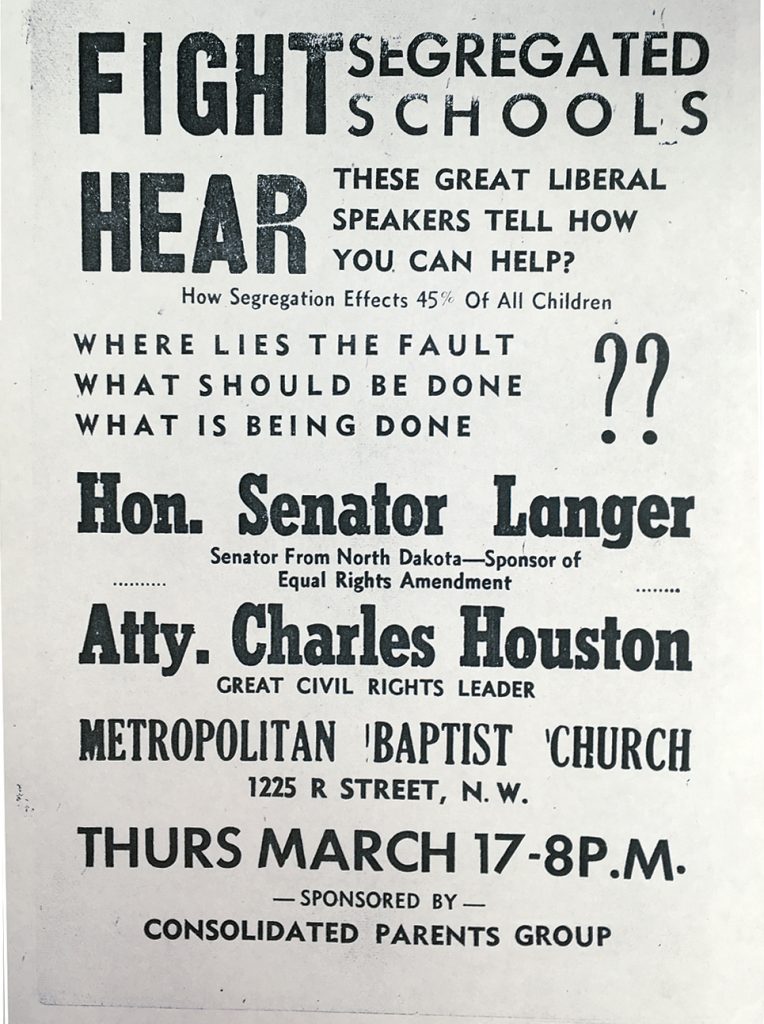

It was a spiritual place and a hotbed of activism.

“[Segregation] kept us all in the same community and patronizing our own businesses. We learned to produce and provide everything we needed, and because of that the community flourished.”—B. Doyle Mitchell Jr., whose grandfather founded Industrial Bank in 1934.

*Correction: Due to incorrect information supplied with a photo, a picture of the Hammond Dance Studios was misidentified.

This article originally appeared in the February 2017 issue of Washingtonian.