Sheldon Epps needed a play. It was 2013, and the man who killed Florida teenager Trayvon Martin had just been acquitted, sparking widespread outrage and intense conversations about racism in America. As artistic director of the Pasadena Playhouse in Los Angeles, Epps knew he had to find a way to respond to the issues stirred up by this shooting. But how?

Then Epps, a longtime theater and television director, had a flash of inspiration. Maybe his way in was through the trial—the jury that had decided to let Martin’s killer go. So he decided to stage Reginald Rose’s psychologically complex 1954 play, Twelve Angry Men—only instead of focusing on an all-white jury, Epps made half of the deliberators Black. “The sad thing is that the play was written over 50 years ago,” he says, “and when we put it on the stage, without changing a word, it’s relevant and immediate. That’s wonderful theatrically but kind of a tragedy politically and societally.”

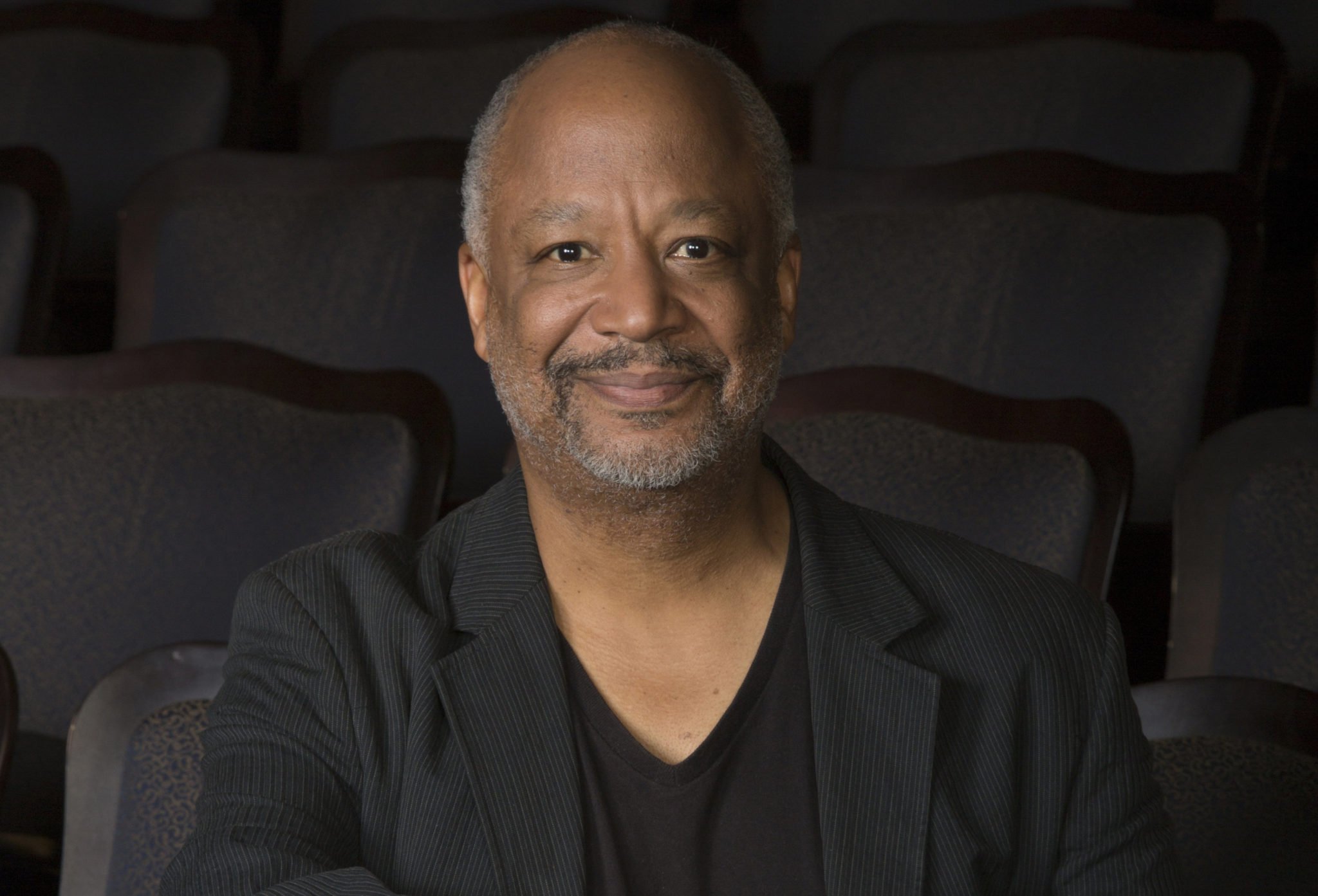

The revamped production was a success, and in 2019 Epps brought it to DC for a run at Ford’s Theatre. Now he has forged a much closer relationship with Ford’s, signing on in August as senior artistic adviser. Epps’s new role comes with a mandate to improve the theater’s diversity efforts and bring more artists of color to its stage.

Ford’s is an unusual institution—better known as the site of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination than as a place to see envelope-pushing theater. Its stage was dark for more than a century after Lincoln was shot, but it reopened in 1968 as a working theater and tourist site that’s co-run by the National Park Service. Perhaps you’ve been to check out its annual staging of A Christmas Carol or to see revivals of Broadway staples like Hello, Dolly! Or maybe you’ve visited just to gawk at the preserved presidential box where John Wilkes Booth’s bullet found its target.

The theater actually has a long history of presenting diverse work, dating back to the 1970s, when gospel musicals were a regular part of the programming. In recent years, The Wiz, Fly (about the Tuskegee Airmen), and the August Wilson plays Jitney and Fences were among the multicultural offerings. But the vast majority of the playwrights and directors that Ford’s has tapped in the past have been white and male.

Last year, Ford’s head, Paul Tetreault, decided he wanted to do more, especially as the American theater world was—like a lot of institutions—grappling with larger issues of racism and representation. His decision to bring Epps aboard full-time signals a significant investment in diversity. Epps, meanwhile, sees his role as an expansion of the theater’s efforts instead of a major zig-zag. “If I didn’t feel this was something Ford’s had focused on over many years,” he says, “it wouldn’t be a job that I was interested in.”

When Epps started at Ford’s in August, all of its programming was on hold due to the pandemic. But that ongoing pause has allowed for some radical steps. Epps and Tetreault decided to scrap much of the theater’s previously mapped-out schedule. So when the crisis finally eases and the curtain rises again, there will be no production of the crowd-pleasing musical Guys and Dolls, as originally planned.

Instead, Epps and Tetreault—working with the theater’s artistic team, including Kristin Fox-Siegmund, José Carrasquillo, and Erika Scott—will offer a trio of works about civil-rights leaders, starting with the Epps-directed My Lord, What a Night, a play about the surprising friendship between Marian Anderson and Albert Einstein. There will also be runs of Necessary Sacrifices, which explores Lincoln’s relationship with Frederick Douglass, and Katori Hall’s The Mountaintop, the first play by a Black woman to be produced at Ford’s in decades. “We started thinking about projects that dealt with big racial issues,” says Epps, who expresses his thoughts in a slow baritone that’s both commanding and a bit hypnotic. “What valuable and incredible things can come out of discovering our commonalities, those things that bind us together and unify us?”

Epps has been pushing for more diversity in theater for most of his career. Having grown up in Los Angeles and New Jersey, he started as a stage actor, then cofounded a small theater company in New York. His Broadway breakthrough came in 1982 with the musical revue Blues in the Night, which he created and directed. (It was nominated for a Tony as Best Musical.) Later, while continuing his theatrical career, Epps also moved into TV, directing episodes of Friends, Frasier, and Girlfriends, among other shows.

When he took the top creative job at Pasadena Playhouse in 1997, Epps became one of the first Black artistic directors in American regional theater. The playhouse was in rough financial shape at the time, and it catered to an audience that skewed older and whiter. His hiring wasn’t universally welcomed. “When he first arrived, there was a political cartoon in a local paper of him boiling in oil and little old ladies of Pasadena dancing around the kettle,” says Seema Sueko, who worked with Epps in Pasadena from 2014 to 2016 and was until recently Arena Stage’s deputy artistic director. “I think most people would’ve said, ‘I cannot stay here.’ He instead said, ‘I must make art here.’ ”

So that’s what he did, and in the process Epps brought in younger, more diverse audiences. The work he presented was notably more multicultural, as were the actors onstage. The strategy wasn’t just more equitable—it was also profitable.

In 2017, after a successful 20-year run, Epps stepped down from his full-time role in Pasadena, and he spent a few years staging plays in various venues. (It was in that capacity that he brought his Twelve Angry Men production to DC.) But when the opportunity came along to reshape the artistic vision of an institution as prominent as Ford’s, Epps decided to accept the challenge.

Now he’s spending much of his time thinking about other ways to push Ford’s forward. The biggest initiative so far—which Epps is spearheading with Tetreault—is called the Lincoln Legacy Commissions. The theater is tapping five playwrights of color to create new productions about people from history. “They are free to examine whatever historical figure they want to examine, no matter the race of that person,” says Epps. “So you might well have a Black playwright writing about Thomas Jefferson or [Atlanta’s first Black mayor] Maynard Jackson.”

Though he acknowledges that decades of grappling with racial issues in theater have left him “wearied by the conversation,” Epps is also “encouraged by the fact that the conversations are happening now in a much more honest way.” And he really does believe that as an artist he can use the stage to help people think about inequality in our country. “Audiences have to come to the theater prepared to be entertained,” he says, “but also to grapple more with the truth—the long, long history of racial injustice in America.”

That was certainly the goal back in 2013 when Epps decided to use that ultra-familiar 1950s play about a divided jury as a way to address contemporary racial violence. “One of the reasons I drifted towards Twelve Angry Men is it does point to possibility,” he says. “The possibility that if we’re willing to open our minds—if we’re willing to genuinely talk and genuinely listen—it is possible that we can come together. It’s not inevitable. And the play doesn’t say that. But the play says it’s possible for us to move closer together—to move forward with consensus.”

This article appears in the March 2021 issue of Washingtonian.