The Tidal Basin’s beloved cherry blossoms are drowning. Twice a day at high tide, brackish water from the Potomac River floods the banks, plunging the walkway and the roots of its 3,800 cherry trees into standing, salty water. The culprit: climate change. As sea level in the Washington area continues to rise faster than anywhere else on the East Coast, the land itself is sinking, the byproduct of a prehistoric ice sheet melting and causing nearby ground to settle. Ongoing development, meanwhile, is causing additional runoff to the Tidal Basin. Leaving the trees and memorials to weather current conditions without intervention would thus be a death sentence for one of DC’s most celebrated sights. As it is, only 4 percent of the 3,020 original trees given to Washington by the Japanese in 1912 remain.

“If nothing is done, it is reasonable to anticipate that in somewhere between 50 and 100 years, the place will be under water,” says Tidal Basin Ideas Lab co-curator Thomas Mellins.

Two years ago, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the Trust for the National Mall, and the National Park Service launched a design challenge called the Tidal Basin Ideas Lab, inviting five US landscape-architecture firms to pitch proposals to save the historic site, or completely reimagine it. The idea was to initiate a conversation and jump-start options for the Park Service to consider, as well as generate excitement among donors who could help fund the future.

These are the results.

The Entropy Solution

The firm that designed Manhattan’s High Line proposes multiple options, the boldest of which begins with surrender. Like a tale of biblical beginnings, the Tidal Basin is left to flood, allowing the memorials to weather the waters. A new elevated walkway mirrors the current loop of trees, albeit from a different perspective. A less extreme plan reworks the landmass around the monuments, allows for partial flooding, and eventually transforms the area into a series of islands. Visitors are still able to explore the Basin via boats and boardwalks connecting the archipelago.

A Critic’s Take: “Most of the buildings on the Mall are less than 100 years old, and we manage to keep them in pristine form. So I think what is being asked here is not ‘Are we going to be able to?’ but ‘Do we want everything to always look as though it was just made?’ ” —Roger Courtenay, who was lead landscape architect for the Eisenhower Memorial and the National Museum of the American Indian and who participated in more than a dozen design projects and studies around the Mall

The Naturalist Approach

The firm that designed the grounds of the National Museum of African American History & Culture wants to move slowly. Rather than redeveloping the landscape, the architects introduce incremental change over the next 70 years. Repairs to the existing floodgates (and later replacement) protect the land, and the creation of floodplain forests helps slow the flow of water. Native flora is introduced over time, ultimately replacing the cherry blossoms and creating new space for visitors to explore via marsh boardwalks.

A Critic’s Take: “It’s not a one-size-fits-all design. It’s suggesting that we need to keep being ready to adjust. And nature can help show us a way.” —Roger Courtenay, who was lead landscape architect for the Eisenhower Memorial and the National Museum of the American Indian and who participated in more than a dozen design projects and studies around the Mall

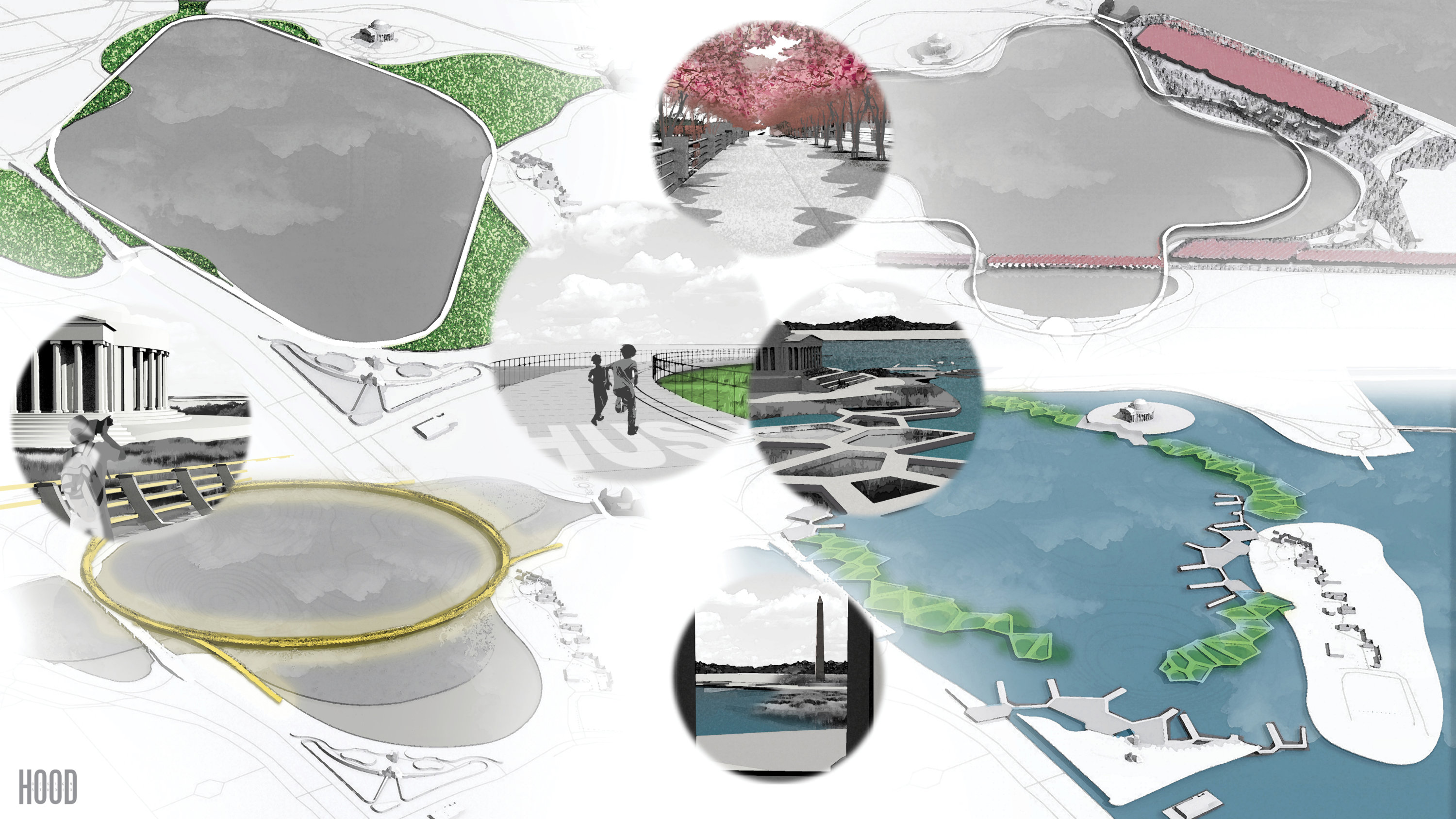

“Hush Harbor”

Headed by Walter Hood, a Black architect who edited an essay anthology called Black Landscapes Matter, this studio suggests different scenarios in graphic-novella form, each embedded with educational experiences about Black history and African Americans’ intimate connections to “hush harbors”: wetland havens where enslaved people met to worship. In one iteration, new floodgates regulate the flow of the Potomac and the fortified trail is enhanced with a narrative about the harbors. A different plan features an elevated track encircling the basin path and providing access to the monuments across the marsh. A third scenario calls for cherry trees in what is currently the south lane of Independence Avenue and the playing fields of West Potomac Park, raised up and away from the water line.

A Critic’s Take: “He suggests that story lines are really important to offering solutions, and he does show for each of those stories a really creative and intriguing way for them to be physically expressed.” —Roger Courtenay, who was lead landscape architect for the Eisenhower Memorial and the National Museum of the American Indian and who participated in more than a dozen design projects and studies around the Mall

The Jetties

DLAND’s solution is relatively straightforward: Create more terra firma to absorb water and provide alternate pathways to the monuments, dispersing foot traffic from the trampled tree roots. The MLK Memorial is moved to an elevated jetty across from Lincoln, creating a new plaza space framed by relocated cherry blossoms. Runoff from the Mall is collected in an ellipse pool within the basin, generating a reflecting-pool-type experience. A newly formed land bridge helps absorb water and extends from the White House axis to Jefferson, creating a direct pathway to access the monument. A green wall behind it forms a protective barrier to safeguard the monument and trees.

A Critic’s Take: “This idea of moving some of the monuments is very intriguing, and very disturbing at one level, but it does show that there could be new relationships amongst monuments.” —Roger Courtenay, who was lead landscape architect for the Eisenhower Memorial and the National Museum of the American Indian and who participated in more than a dozen design projects and studies around the Mall

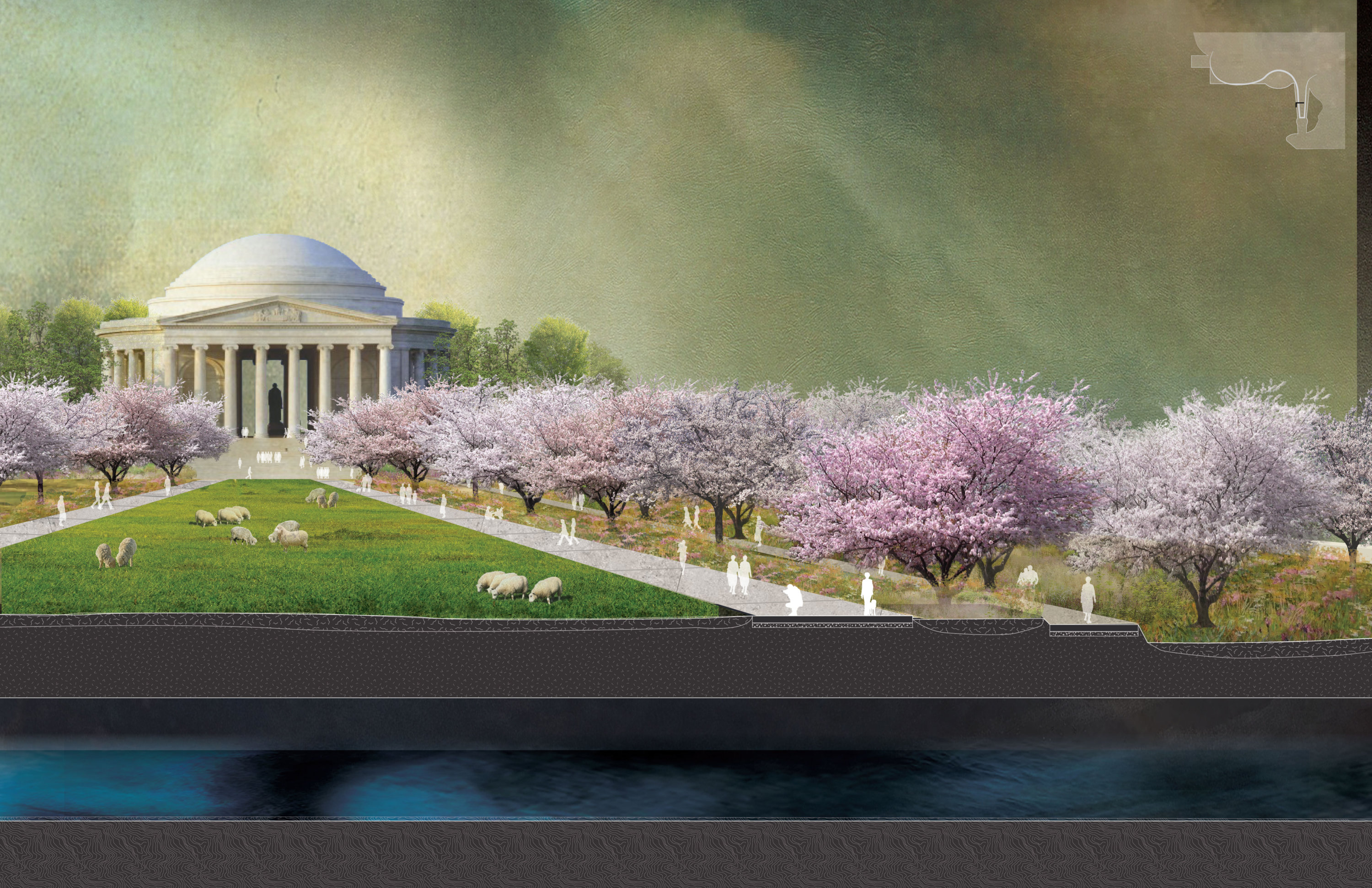

The High Lines

The firm’s approach relies on intertwining pathways. Visitors can choose their own adventure, strolling down the cherry walk, marsh walk, and monument walk for a different experience on each trail. Pathways intersect at an elevated landmass and pedestrian bridge dubbed Independence Rise, protecting the uplands from the tide. The cherry walk, the path farthest up on the newly formed hills, mimics the classic circular route. Meanwhile, the monument walk links Jefferson, FDR, and MLK for ease of passage, absorbing some of the traffic that could otherwise trample the trees. The seawall becomes a pathway of its own along the marsh, with stepped terraces overlooking the basin.

A Critic’s Take: “Their narrative is ‘We’re going to find a way to maintain those cultural stories—Jefferson, MLK, FDR, cherries, water—and we’re going to make it all work environmentally. Don’t give up hope.’ I think that’s actually pretty original and evocative.”—Roger Courtenay, who was lead landscape architect for the Eisenhower Memorial and the National Museum of the American Indian and who participated in more than a dozen design projects and studies around the Mall

What Happens Now?

It’s an open question. The design challenge wasn’t a contest, per se; it was more of a gambit, meant to provoke big thinking among stakeholders and those who may be inspired to play a role. The next steps lie with the National Park Service and a cohort of public commissions that get involved whenever federal land is involved. NPS will launch a master-planning process this year, during which themes from the proposals will be considered. It’s possible that none of these exact visions come to fruition and that instead they help generate new ones. Either way, the hope is that the creative challenge motivates donors inclined to leave their mark on the area. Any effort will require monumental funds: NPS estimates that $500 million is needed in deferred maintenance alone.

A Mini-Timeline of Destruction

What happens if we leave the area to face nature alone

2040

The Jefferson Memorial will stand in four feet of water at high tide.

2070

The MLK Memorial will stand in six feet of water at high tide.

2100

The FDR Memorial will stand in nine feet of water at high tide.

Blossom Watch

1

Feet of water that the cherry trees stand in each day during high tide

6

Inches that Washington is predicted to sink by the year 2100

4%

Portion of the original 3,000 cherry trees from 1912 that remain at the Tidal Basin today

$64

Million Estimated cost of repairing the Tidal Basin sea wall alone

90

Number of trees that need to be replaced each year due to drainage and disease

This article appears in the April 2021 issue.