One day in the early 1860s, a Union soldier named Stephen signed his name on the wall of a Virginia farmhouse, adding his tag to hundreds of others that covered the inside of the structure. The house, today known as Historic Blenheim and located in the City of Fairfax, has fascinated historians for decades, in large part because of all this graffiti. But until recently, only a small portion of the scrawlings—primarily in the attic—had been visible. The rest of the house’s secrets have been buried under layers of paint and wallpaper.

So while researchers had learned about some soldiers who passed through—men such as Henry van Ewyck, a Dutch immigrant in the 26th Wisconsin Infantry who deserted after recovering from illness at Blenheim, then returned to his unit and fought at Gettysburg—much of the house’s past was lost. Stephen’s last name, for example, had been covered up by more than a century’s worth of decoration. Who was he? And what else might the house reveal if historians could access its treasures without destroying its surfaces?

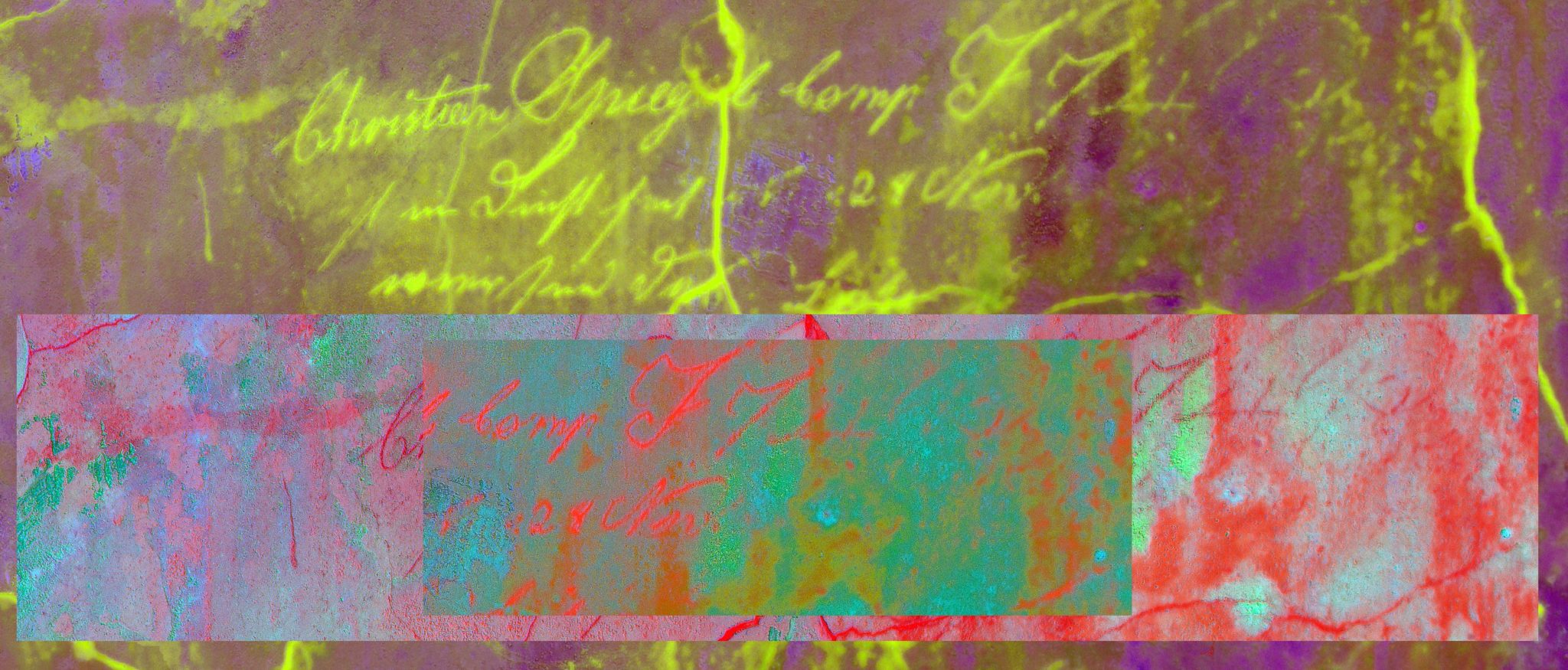

Recently, those questions have started to be answered, thanks in part to the efforts of Mike Toth, an Oakton-based specialist in multispectral imaging: the use of high-tech cameras to see what the human eye cannot. In 2019, Toth volunteered his services for a day, and one of the things that he revealed was the first letter of Stephen’s last name: an M. That was enough of a clue for Andrea Loewenwarter, a historian who has been studying the names on Blenheim’s walls since the late ’90s. She searched historical records and was soon able to locate her man. As a result, we can now connect the signature to Stephen W. Millichamp, who served in the 1st Michigan Cavalry, mustered out of the Army in 1865 as a second lieutenant, and died in 1911 in San Diego. Loewenwarter found his great-great-great-grandson, who sent some photographs of Millichamp wearing a bowler hat underneath palm trees. He is the 123rd person who has been matched to specific bits of writing on Blenheim’s walls so far. “Each of these soldiers provides us with a story of the United States,” says Loewenwarter.

Now the multispectral-imaging project is expanding. In August, the National Park Service’s National Center for Preservation, Technology and Training approved a grant that will allow Toth to continue his work. Loewenwarter will be able to identify even more soldiers and uncover their stories. Of course, the house has a story as well.

Blenheim was built in 1859 by Albert and Mary Willcoxon. Albert, a prosperous farmer, was also a Confederate sympathizer, and after the first battle of Fairfax Court House in 1861—which resulted in the Civil War’s first fatalities and occurred just a mile away—the Willcoxons fled. The area came under complete Union control beginning in March 1862, and Union soldiers camped on Willcoxon’s land, waiting for the orders that would send them off into battles such as Gettysburg and Manassas. During the winter of 1862–63, Blenheim was also used as part of the US’s reserve military hospital system.

Nobody knows who first scribbled a name on the Willcoxons’ walls, but as troops filtered through, the practice caught on fast. There are thousands of inscriptions throughout the house, along with all sorts of wall drawings: cartoon scenes of war, musical notes, even some hand-drawn pornography.

Then, in 1863, Albert Willcoxon took a loyalty oath to the Union, and the couple eventually moved back into the house. Their decorating taste did not, unsurprisingly, include the scrawled names of random Union soldiers, so they covered the graffiti up. Over the next four generations, Willcoxon descendants added layers of paint and wallpaper. Other than in the attic, the inscriptions were mostly obscured.

The Willcoxons’ last descendant, William Scott, lived in the house until his death in the late 1990s. Loewenwarter, who has a master’s in museum education, lived nearby at the time, and she was part of a group of five neighbors—who included David L. Meyer, now mayor of the City of Fairfax—who formed a coalition to preserve the house. Based on their efforts, the City of Fairfax bought Historic Blenheim in 1999 for $2.2 million and turned it into a museum.

Recently, Loewenwarter led me on a private tour of the house, which is currently closed to the public due to the Covid pandemic. (The visitor center will reopen May 4.) The attic is off-limits—a fire marshal declared it unsafe—but the rest of Blenheim offers an intriguing look at 19th-century Virginia. You can experience the attic at a nearby visitor center, which has a full-scale model featuring wraparound photos of the graffiti.

After the city purchased the house, conservators tried using chemicals to strip away the paint and wallpaper. Doing so revealed gems such as a multi-part cartoon that depicts a soldier who is running out of both alcohol and patriotism. However, chemical strippers and infrared scans can cause damage to the wall art. Multispectral imaging, on the other hand, is noninvasive, scanning bands of the light spectrum that humans cannot see. Toth captures images using special cameras and then enhances the results with a computer. The technique is now revealing a trove of hidden history—two-dimensional images that Loewenwarter can then transform into three-dimensional histories of those who once passed through. And because of the people Blenheim housed, the effort is “about the common soldier,” Loewenwarter says, unlike what’s studied at some other Civil War sites.

For anyone with a vivid imagination and an interest in the past, walking around Blenheim can be a powerful experience, conjuring the pain of so many former occupants: the enslaved people who toiled there before the war, the scared soldiers on their way into battle, the injured and dying who spent time there afterward, when it was used as a hospital. The house positively vibrates with its history.

For descendants of these soldiers, the place has even deeper meaning. Historic Blenheim has established relationships with several families, including that of Henry van Ewyck. During our tour, Loewenwarter talked about the time when van Ewyck’s 80-year-old grandson came for a look at the attic, where his forebear had written his name in a fancy, looping script on October 29, 1862. During the visit, the man’s daughter was worried about the narrow stairs, but the grandson was undaunted. “I’m going up to see my grandfather’s signature,” he declared, “and if I die on my way down, that’s okay.”